TB871: Chris Argyris and his influence on systems thinking and organisational development

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

Chris Argyris is an influential figure in organisational theory who made significant contributions to our understanding of how individuals and organisations learn and develop. His work, often in collaboration with Donald Schön, offers insights into the mechanisms of learning and the barriers that can hinder effective organisational development. (Note: I discussed some of Schön’s work in my work on module TB872)

Adult-like working environments

Argyris observed that hierarchical structures within organisations often create environments inconsistent with adult-like work settings. He argued that such settings can lead to frustration among employees who value autonomy and responsibility. This observation is encapsulated in his statement:

If hierarchies had their way, they would create work worlds for human beings that were consistent with the features of infancy … those workers who valued adult-like work settings would likely experience a conflict and would likely be frustrated

(Ramage and Shipp, 2020, p. 288)

This critique highlights the tension between hierarchical control and the need for more democratic, participative work environments. Argyris believed that when employees are treated as adults, they are more likely to be motivated, satisfied, and productive.

Espoused theories vs. Theories-in-use

One of Argyris’ most notable contributions is the distinction between ‘espoused theories’ and ‘theories-in-use’. The former are what individuals claim to follow, while the latter are the actual principles that govern their behaviour in practice. Argyris and Schön explain:

Espoused theories, which people believe in, advocate, and claim to be those which govern their actions; and theories-in-use, which in real situations actually govern a particular individual’s actions.

(Ibid., p.289)

This distinction is crucial because it reveals the often significant gap between what people say they do and what they actually do. Recognising this gap is the first step toward more honest self-assessment and organisational improvement.

Theories-in-use comprise three interconnected elements:

- Governing variables: These are the assumptions and factors that individuals aim to keep within acceptable levels.

- Action strategies: These are the methods individuals employ to maintain the governing variables.

- Consequences: These are the outcomes of the actions, which can be either intended or unintended.

Understanding these elements helps clarify why individuals often behave differently from what they profess. For instance, a manager might espouse the value of teamwork but, in practice, might prioritise individual achievements due to underlying beliefs about competition and reward.

Argyris illustrated the concept of theories-in-use with simple, everyday examples to demonstrate their automatic and often subconscious nature. For instance, he noted:

If we had to think through all the possible responses every time someone asked, ‘How are you?’ the world would pass us by.

(Ibid.)

This example highlights how ingrained and automatic our responses can be, guided by deeply held theories-in-use. Such automatic responses can be beneficial in routine interactions but problematic in situations requiring thoughtful reflection and change.

Single and Double-loop learning

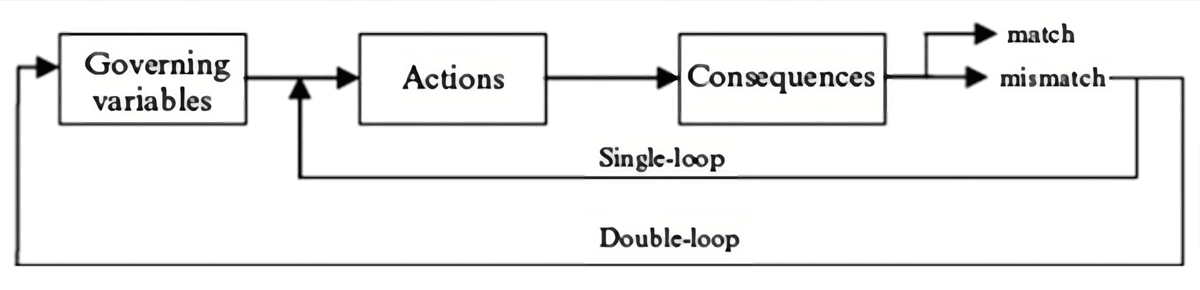

Argyris introduced the concepts of single-loop and double-loop learning to describe how organisations adapt and evolve. Single-loop learning involves making adjustments to actions to better meet existing objectives. In contrast, double-loop learning involves questioning and altering the underlying assumptions and goals themselves. He stated:

If observing the consequences of actions results in changes in assumptions about what outcomes are desirable, that would be double-loop learning.

(Ibid.)

A diagram illustrating single and double-loop learning can effectively visualise these concepts:

The diagram shows that governing variables influence actions, which lead to consequences. In single-loop learning, if a mismatch between actions and desired outcomes is detected, adjustments are made to actions to better align with governing variables. In double-loop learning, a mismatch prompts reassessment and potential changes to the governing variables themselves. This represents how single-loop learning corrects actions, while double-loop learning reevaluates underlying assumptions.

So, single-loop learning is like a thermostat that adjusts heating or cooling to maintain a set temperature. Double-loop learning, however, questions whether the current temperature setting is appropriate.

Model I and Model II behaviour

Argyris identified two typical patterns of behaviour in organisations: Model I and Model II. Model I behaviour focuses on unilateral control, striving to win, suppressing negative feelings, and acting rationally. This behaviour is closely linked to single-loop learning and often results in defensive reasoning:

Model I behaviour is closely linked to single-loop learning: its values include being in unilateral control of situations, striving to win rather than losing, suppressing negative feelings in oneself and others, and acting rationally. (Ramage and Shipp, 2020, p. 290).

In contrast, Model II behaviour encourages valid information sharing, promoting free choice, and assuming personal responsibility. It aligns with double-loop learning and fosters a more open and reflective organisational culture:

Model II behaviour is linked to double-loop learning: its values include utilizing valid information, promoting free and informed choice, and assuming personal responsibility to monitor effectiveness.

(Ibid., p.290)

Defensive reasoning

Defensive reasoning is a significant obstacle to organisational learning. Argyris explained how individuals use defensive reasoning to protect themselves from threats or embarrassment, which can stifle learning and innovation:

Individuals keep their premises and inferences tacit, lest they lose control; they create tests of their claims that are self-serving and self-sealing.

(Ibid.)

This behaviour creates an environment where mistakes are hidden, and learning opportunities are missed. Defensive reasoning leads to a culture of blame and fear, rather than one of openness and continuous improvement.

Four basic values

Argyris identified a universal human tendency to design actions based on four basic values:

- To remain in unilateral control.

- To maximise ‘winning’ and minimise ‘losing’.

- To suppress negative feelings.

- To be as ‘rational’ as possible.

These values often lead to defensive behaviours and the defensive reasoning mentioned above, which can hinder genuine learning and adaptation (Ibid., p. 293). By recognising these tendencies, individuals and organisations can begin to adopt more open and reflective practices.

References

- Ramage, M. and Shipp, K. (2020) Systems Thinkers. 2nd edn. Milton Keynes: The Open University/London: Springer.