TB872: Juggling the C-ball (Contextualising)

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category. This particular post is part of a series which is framed and explained here.

Chapter 7 of Ray Ison’s Systems Practice: How to Act focuses on the C-ball (Contextualising). This concerns the ways that systems practitioners contextualise specific approaches in real-world situations. It involves understanding the relationship between a systems approach and its application, going beyond merely choosing a method. So, in what follows, I’m going to reflect on what I’ve learned in the chapter, applying it to Systemic Inquiry 1 (me as a learner developing my systemic practice) and Systemic Inquiry 2 (my ‘situation of concern’).

Systemic Inquiry 1

As I’ve commented in previous posts, I think my assumption on starting this MSc was that I’d learn a bunch of approaches (‘methods’) and how to apply them to situations. What I’m actually learning is much more valuable, and deeply philosophical, than that. In the words of Ison, it’s not simply ‘horses for courses’ where a ‘horse’ (i.e. approach) is matched with a ‘course’ (i.e. situation). “This is because” he says “taking a systems approach involves addressing the question of purpose” (Ison, 2017, p.158).

Despite many and varied literature and statements to the contrary, it is not possible to generalise an approach across all contexts, as the climate emergency is showing. A one-size-fits-none approach has led to unsustainable approaches and destroyed or deprecated indigenous ways of knowing. As a competitive swimmer in my youth, and an occasional visitor to the pool at our local leisure centre, I quite liked Ison’s analogy which kicks off the chapter:

The lanes in my pool are labelled slow, medium, fast, and sometimes, aquaplay. Usually there is at least one lane of each. Over time I have come to contextualise my swimming to a set of circumstances in which I understand that what is fast and what is slow differs with time of day (i.e. who the other swimmers are; whether lap training is happening, etc.). I have also come to know that at certain times I can swim in the aquaplay lanes, or that at others I am best to consider myself fast or slow. Because I have flexibility to adapt my swimming to a changing situation I find my practice usually works very well for me … and presumably those who manage the pool. For me this is an example of juggling the C-ball in my swimming practice.

Ison (2017, p.155)

The temptation as a consultant working with other organisations is to think that you’ve seen the exact situation being presented before; that it is the same as a system in which you’ve previously intervened. Although there are, of course, great overlaps and similarities between organisations and the way the people within them approach the world, no two situations are identical.

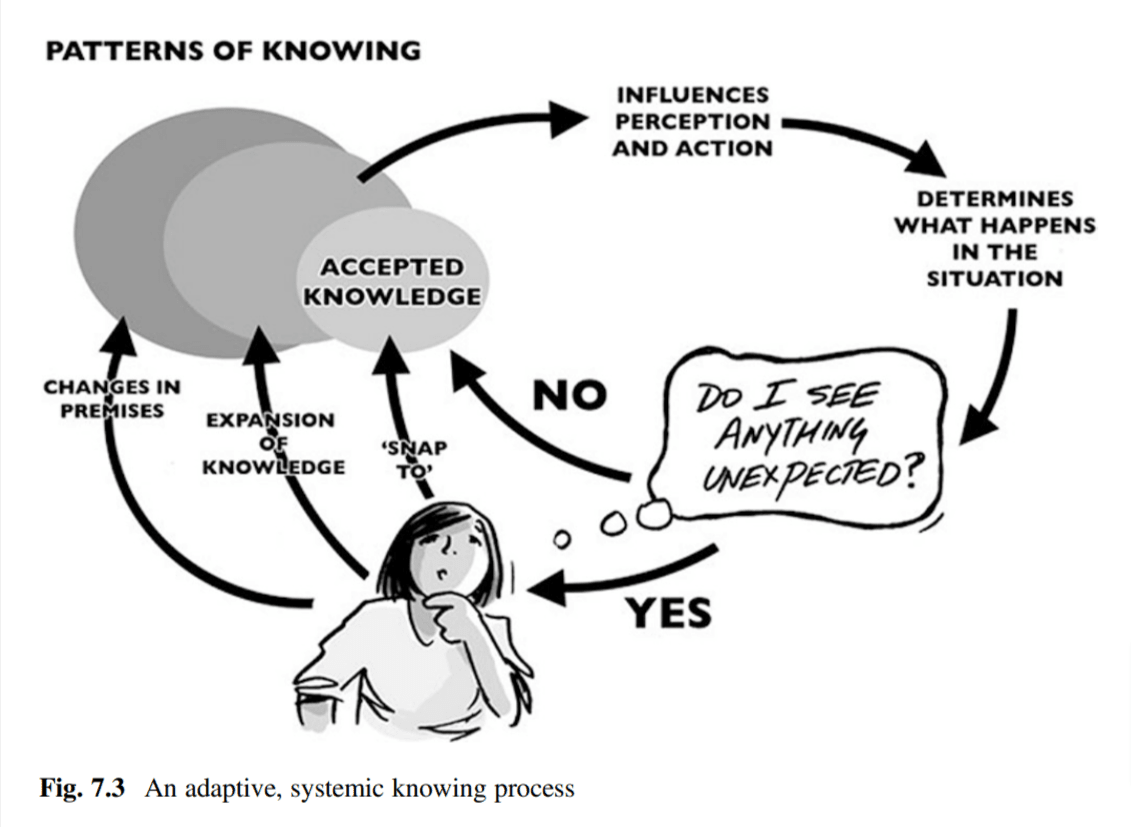

What I found fascinating about this chapter was the way that Ison explicitly rejects the common ‘cyclical’ approach to systems thinking where knowledge leads to action, which leads to reflection, then more knowledge, and so on. Instead, he includes the following diagram, which is a system of interest which as “an epistemological act opens up opportunities to break out of the inner accepted-knowledge reinforcing cycle” (Ison, 2017 p.162)

To me, this is reminiscent of Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions but on a more personal level. During the process of ‘normal science’ (i.e. accepted knowledge or ways of doing things) ‘anomalies’ are observed in the phenomena. These in turn lead to explanations to try and explain them within the bounds of accepted knowledge. When these anomalies accumulate, a period of ‘revolutionary science’ occurs where new frameworks (which are always being proposed) become more appealing. Eventually, the ‘revolutionary science’, in the form of a different framework, becomes the new ‘normal science’.

Kuhn’s approach is something I’ve been aware of since my first year at university as an undergraduate, so it’s something I’ve had at the back of my mind for more than half of my life. Applying it here may or may not be appropriate, but it helps develop my understanding of what is going on when a practitioner contextualises their approach to a situation. Challenging accepted knowledge is part of why a consultant is brought in to help an organisation. As I mentioned in a previous post, organisations can seem to have no common sense of purpose, which I suppose is because they’re drifting along in the comforting fiction of accumulated accepted knowledge.

Returning to my assumptions on starting this MSc, I’m pleased that Ison specifically calls out that systems practice “does not have to rely on established methods or ‘methodologies'” and that it “can be contextualised to unfolding, changing circumstances” (Ison, 2017, p.185). We were talking during one of our WAO co-working sessions yesterday about how soul-crushing it must be to run the same workshop or give the same presentation time after time. Just because other people share that they have done something on LinkedIn does not make it good practice.

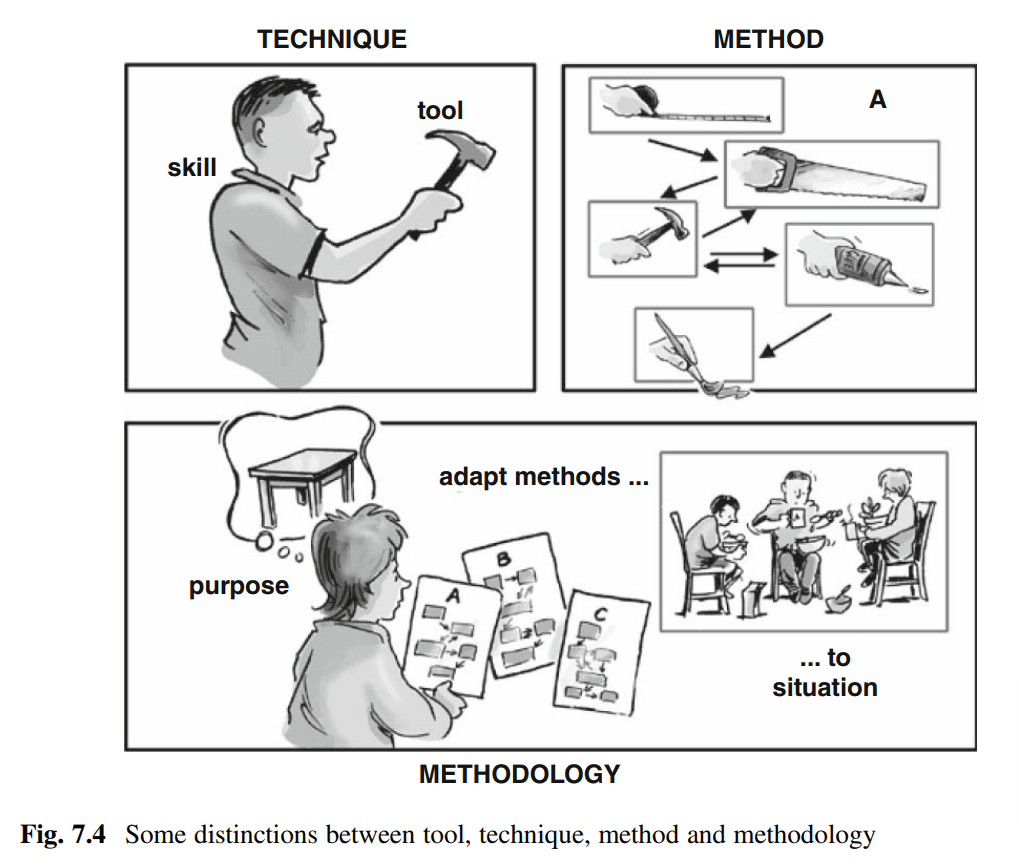

Another useful diagram which aided my thinking in this chapter was the one that illustrates the difference between a technique, a method, and a methodology:

You see a lot of people sharing ‘tools and techniques’ and perhaps running workshops on ‘methods’. However, the systems thinker goes beyond this to adapt methods, based on a particular purpose, to a situation. This means that they have to have a wide range of methods in their methodological toolkit.

There is nothing wrong with learning a method and putting it into practice. How the method is put into practice will, however, determine whether an observer could describe it as methodology or method. If a practitioner engages with a method and follows it recipe-like, regardless of the situation, then it remains method. If the method is not regarded as a formula but as a set of ‘guidelines to process’, and the

Ison (2017, p.168)

practitioner takes responsibility for learning from the process, it can become methodology. The transformation of method into methodology is something to strive for in the process of becoming an aware systems practitioner and of course one can draw guidelines from several methods to develop a methodology in any situation.

This is a really key bit of learning for me in terms of how I approach both this module and my everyday work. For example, it is of course absolutely fine to use a similar method with multiple clients, but the way that I/we use it has to be contextualised. Also, the choice of method has to be intentional and reflexive, and not be merely ‘just the way we do things’.

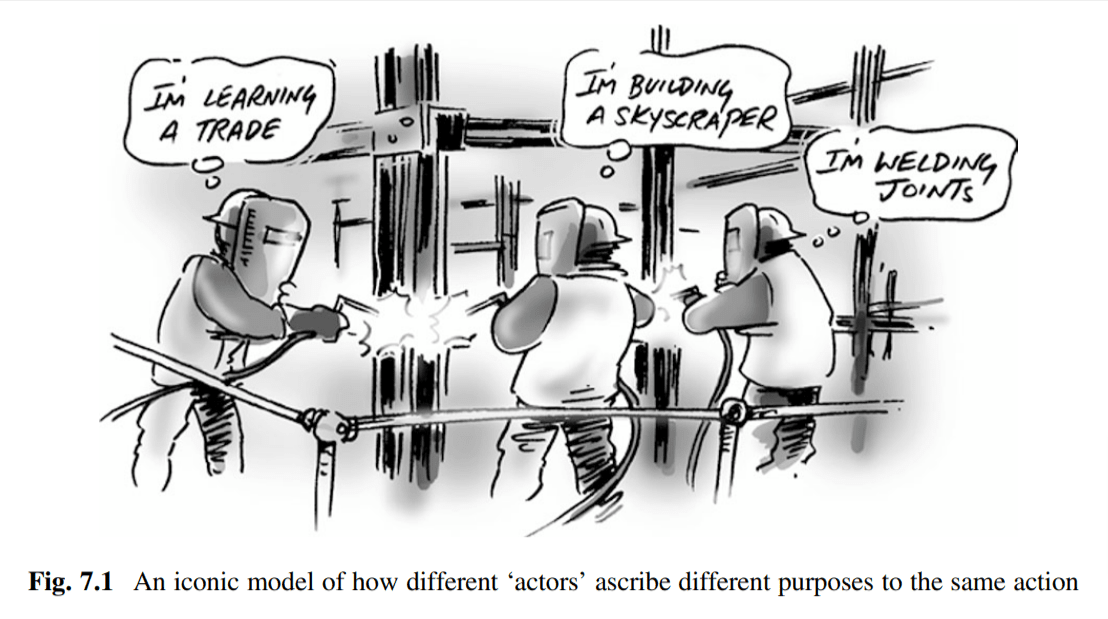

I thought it was interesting that Ison pushed back a little on Stafford Beer’s famous quotation that “the purpose of a system is what it does” (Ison, 2017, p.159). He wonders whether Beer meant it in a tongue-in-cheek way, which I hadn’t considered, but is concerned that “this statement runs the risk of objectifying ‘the system'” (Ison, ibid.) The way that I have understood this quotation since coming across it relatively recently is that there is no one ‘purpose’ of a system, so if you are going to ascribe it a single, teleological aim, then, well, that is just what it currently does. So if, to use an example from my own professional experience, the DWP’s benefits system marginalises and excludes people who find it difficult to claim Universal Credit, then this is the ‘purpose’ of the system.

The final thing I want to include from this chapter in terms of the development of my own systemic practice is the comparison of ‘hard’ versus ‘soft’ traditions of systems thinking. Ison adapts a table from Checkland (1985) on p.160. Below are my highlights in bullet point form, with the fundamental difference in approach being that the ‘hard’ tradition aims to apply systematic methodologies to solve problems, akin to engineering, while the ‘soft’ tradition is more interpretive, and emphasises understanding and learning over finding a single correct solution.

- Both traditions use system models as a means to engage with the complexities of the world, but have different foundational assumptions. ‘Hard’ systems thinking approaches consider models as direct representations of reality (ontologies) and soft systems viewing them as frameworks for understanding (epistemologies).

- Each tradition adopts a specific linguistic framework. ‘Hard’ approaches to systems thikningfocus on the terminology of ‘problems’ and ‘solutions,’ which indicates a desire for ‘definitive answers’. This is in contrast to the ‘soft’ systems thinking language of ‘issues’ and ‘accommodations,’ which reflects perhaps a more nuanced engagement with situations.

- The ‘hard’ tradition focuses on ‘goal seeking’, as opposed to the ‘soft’ tradition’s focus on learning. ‘Hard’ systems thinking approaches aim to engineer precise solutions to problems, whereas the ‘soft’ systems thinking tradition is more interested in continuous inquiry, and acknowledges the absence of absolute answers.

- ‘Hard’ systems thinking approaches tend to neglect the human and subjective elements of situations, instead favouring logic and objectivity. ‘Soft’ systems thinking, meanwhile, maintains an awareness of the limitations of linear logic and the importance of human factors.

- While both approaches are grounded in systems thinking, the ‘hard’ tradition is more prescriptive and oriented towards ‘techniques’. This might be suitable for stakeholders looking for structured approaches. The ‘soft’ tradition is more inclusive and adaptable to professional practice, emphasising the inescapability of the human side of situations.

Systemic Inquiry 2

Now, I’ll move onto my situation of concern (S2), which is the work that We Are Open Co-op (WAO) is doing with the Digital Credentials Consortium (DCC) around Verifiable Credentials (VCs). We’re helping with documentation and asset-creation.

To me, the image below is key in helping understand how we can make a difference in helping the DCC with the adoption of VCs. There is no one view of the ecosystem and, as I have said in previous posts, everyone has different incentives.

For example, some people are interested in making money, others in saving it through ‘efficiency’. Some are just interested in the technological innovation involved, while others just don’t want to be left behind. What I think is perhaps missing from this diagram is the emotions involved: for example ‘fear’ or ‘enthusiasm’. Quite often, people adopt other people’s approaches to situations they don’t know much about, particularly if it means they err on the side of caution.

One of the things we need to consider with S2 is that, especially in the realm of Higher Education (HE), there is ‘legitimate knowledge’ which “conserve[s] manners of thinking and acting that have evolved over time”. This happens to such an extent that “organisations themselves come to be described as having a culture within which conceptions as what counts as legitimate knowledge are enacted and maintained” (Ison, 2017, p.169).

This takes me back to discussions around mental models and metaphors, and my post about the meta-narrative for this systemic inquiry. In particular, it’s increasingly clear as I get into this module that the ‘institutional antibodies’ of the HE system were in full effect when dealing with the threat of Open Badges. This is why they were ‘reinvented’ and reconceptualised as microcredentials, fully owned and operated by the HE sector. It seems clear, then, that positioning VCs as ‘legitimate knowledge’ could be key for wider adoption

In a prior post, I outlined the difference between purposeful and purposive framing:

- Purposeful framing – refers to framing directed towards a specific goal or objective (i.e. focused on my learning and development as a practitioner)

- Purposive framing – refers to framing that is intentional but with a broader or more holistic focus (i.e. not just about my goals, as it considers dynamics, stakeholders, and potential outcomes)

It’s always tempting to think that you know what is best, and particularly so when there’s a technology involved for which you personally have a utopian vision. However, this purposeful framing is not always useful in creating change. A purposive framing can be more useful, but even that comes with a health warning:

[M]any people have a propensity to pursue purposive behaviour that assumes both purpose and measures of performance, rather than engaging stakeholders in a dialogue in which purpose is jointly negotiated. This can have unfortunate consequences.

Ison (2017, p.163)

One of the things that I’ve ‘struggled’ with during my career (and I don’t often use that word) is setting appropriate boundaries. I don’t mean this in a weird sense, but in a systems sense! As Ison quotes Ulrich (1996) as saying, “we cannot conceive of systems without assuming some kind of systems boundaries”. Otherwise “systems thinking makes no sense” (Ison, 2017, p.165).

Thankfully, Chapter 7 includes some help in terms of boundary-setting, both from Ulrich (2000) and Churchman (1971). I’ll quote the latter for the sake of brevity, which are adapted by Ison and found on p.164-165. These are the conditions which need to be fulfilled for a designed system (S) to demonstrate purposefulness.

- S is teleological (or ‘purposeful’)

- S has a measure of performance

- There is a client whose interests are served by S

- S has teleological components which co-produce the measure of performance of S

- S has an environment (both social and ecological)

- S has a decision maker who can produce changes in the measure of performance of S’s components and hence changes in the measure of performance of S

- S has a designer who influences the decision maker

- The designer aims to maximise S’s value to the client

- There is a built in guarantee that the purpose of S defined by the designer’s

notion of the measure of performance can be achieved and secured

When coupled with the three roles that seem to be always present in Soft Systems Methodology (SSM), this seems quite a powerful approach. The following is taken from Checkland and Poulter (2006) via Ison (2017, p.169):

- A person or group who had caused the intervention to happen, someone without whom there would not be an investigation at all – this was the role of ‘client’

- A person or group who were conducting the investigation – this was the role of ‘systems practitioner’

- A person or people who could be named and listed by the practitioner who could be regarded as being concerned about, or affected by the situation and the outcome of the effort to improve the situation – this was the role of ‘owner of the issue(s) addressed’.

I think I need to spend some more time thinking about this and potentially applying it to this situation, probably with the help of Laura’s brain. I’ve already included a lot of images from this chapter, but I’m going to include one more and deal with the potential copyright issues later (fair use for learning!)

This image makes a mockery of the idea of ‘information transfer’, especially in a non-digital context. It’s something we need at the forefront of our minds when dealing with all of our clients, not just in the situation of concern I’m labelling S2. For example, I’ve pulled out of working with one particular network we’re part of, with the last straw being a complete lack of understanding of how learning actually happens. What they wanted is extremely well depicted in the illustration above. It doesn’t work. It never has.

This chapter around Contextualisation has helped me understand that helping successful change come about in my situation of concern depends on several factors. I need to ensure that we have a clear boundary on the system in which we’re intervening. We need to understand the motivations of different actors (stakeholders) involved. I have to make it clear that we’re not ‘delivering information’. We need to have a purposive framing which draws on the ‘soft’ tradition of systems thinking, adapting methods to our context.

In this post, I didn’t go into the reading that’s included in this chapter because it was actually included in a previous activity. This module is a bit ‘weird’ in that it encourages us to read Systems Practice in a non-linear order.

References

- Ison, R. (2017). Systems practice: how to act. Springer, London.

Top image: DALL-E 3