TB872: The PFMS heuristic

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

The word heuristic comes from the Ancient Greek and means ‘to find’ or ‘discover’. In modern usage we use heuristics as practical tools for problem-solving, decision-making, or self-discovery. The idea is that they’re not something that necessarily generate ‘perfect’ results, but that they nevertheless lead to a satisfactory solution.

For example, a simple (and somewhat trivial) heuristic where I live in the north east of England would be to wear waterproof shoes when going out from October until March. It might not be wet when you go out, but the chances are the weather could turn at any point. It’s not a perfect solution, as your feet could overheat, or you might not look as stylish as you would otherwise have wished, but on the whole this is outweighed by mostly having dry feet.

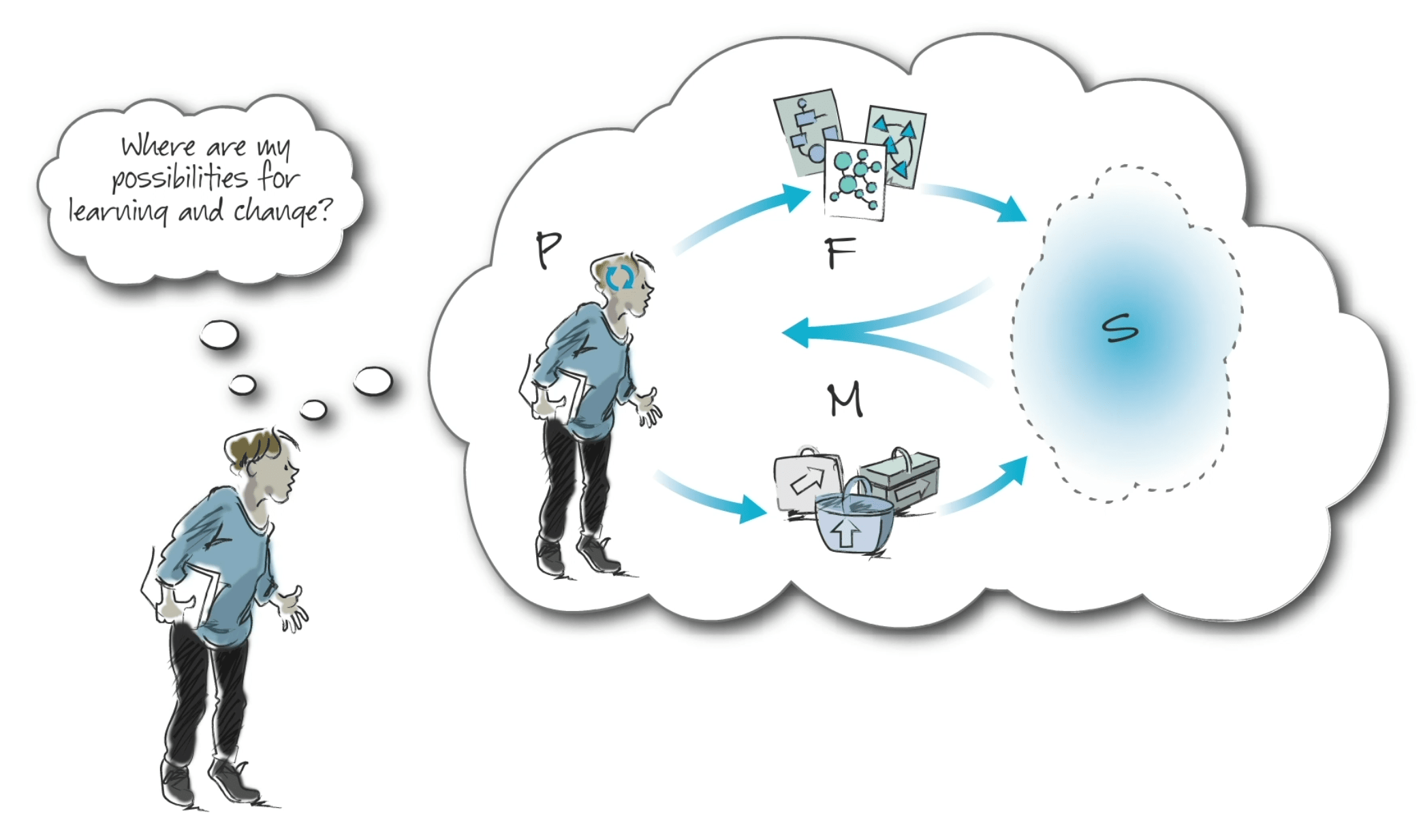

In module TB872, students are presented with the PFMS heuristic which I mentioned in my first post about this MSc. We discussed this in the tutorial I attended last night. Here’s my understanding of the different elements:

- Practitioner (P): this represents me, either in the context of the module or in the situation to be examined. Everyone is a practitioner in terms of the various aspects of our lives; this could be studying but also in our working lives, parenting, etc. Recognising that our practice is situated and embodied is essential as it means acknowledging that we are central to our own practice — and that we are influenced by our surroundings, experiences, and history.

- Framework (F): this is the theoretical and conceptual base from which you can understand and approach the situation under consideration. We all have a ‘tradition of understanding’ which we bring to situations under consideration. I currently think of this in terms of W.V. Quine’s web of belief, in which we have things which are more core or more to the periphery of our belief systems. So, for example, the ‘framework’ which we bring to a situation could be a formal one, but equally it could be a hodge-podge of correct, incorrect, useful, and tenuous ideas.

- Methods (M): these are the things that you use to practically apply theoretical concepts from the framework of ideas. They can also be thought of as ‘tools’ to help engage with, explore, and understand the situations we encounter as practitioners. So, for example, whereas the idea of ‘interconnectedness’ or ‘holism’ might be a framework, the method by which we instantiate this could be through rich pictures, which help us visually see how everything is connected.

- Situation (S): this refers to the specific context or situation in which we find ourselves practicing. In TB872, the situation is the module itself, whereas in my day-to-day work this might be the organisational change that we’re helping a client with. In my personal life, a ‘situation’ could be managing my migraines through a combination of nutrition and exercise.

The PFMS heuristic is a tool to help us think about our practice within the module. What I like about it is that it helps us think about praxis (i.e. theory-informed practice) and gives us a way of separating out, for example, the theoretical frameworks from the methods by which we apply them to a situation.