Utopia, pedagogy, and G-Suite for Education

This week, I’ve been over in Jersey helping a school with their educational technology. In particular, I’ve been doing some training on G-Suite for Education (as Google now call what used to be ‘Google Apps’). The main focus has been Google Classroom but, as this is basically a front-end for the rest of G-Suite, we spilled out into other areas.

A bit of history

I first used G-Suite for Education back when I was a classroom teacher. We didn’t have it rolled out across the school but, back then, and in the school I was in, I was left to just get on with it. So I can remember being administrator, sorting out student accounts, forgotten passwords, and the like. The thing that impressed me, though, was the level of collaboration it encouraged and engendered.

Then, when I became Director of E-Learning of a new 3,000 student, nine site Academy in 2010, I rolled out G-Suite for Education for all 500 members of staff. It worked like a dream, especially given some of the friction there was harmonising different MIS and VLE configurations. The thing that I valued most back then was the ability to instantly communicate between sites by using a tool which has now morphed into ‘Hangouts’.

At that time, I was a bit of a pioneer in the use of Google’s educational tools, which is why Tom Barrett and I, along with some others in our network, were ‘Lead Learners’ at the first UK Google Teacher Academy. That’s grown and grown in the intervening period, while I’ve been working in Higher Education, at Mozilla, and consulting.

Back to the future

Fast forward to the present, and we’re in a very different educational technology landscape. Where once there seemed to be new, exciting services popping up every week, the post-2008 economic crash landscape is dominated by large shiny silos. The dominant players are Google, Microsoft, and Apple — although the latter’s offering seems less all-encompassing than the other two.

I have to say that I’m a bit biased in favour of Google’s tools. I’m not a big fan of their business model, although that’s a moot point in education given that students and staff don’t see adverts. It’s a much more ‘webby’ experience than other platforms I’ve used.

The more I get back into using G-Suite for Education the more I appreciate that Google doesn’t prescribe a certain pedagogy. The approach seems to be that, while particular apps like Classroom allow you to do some things in a certain way, there’s always other ways of achieving the same result. It’s also extensible: there’s loads of apps that you can add via the Marketplace.

So what?

OK, so that’s all very well and good, but what has that got to do with you, dear reader? Why should you care about my experiences and views on Google’s education offerings?

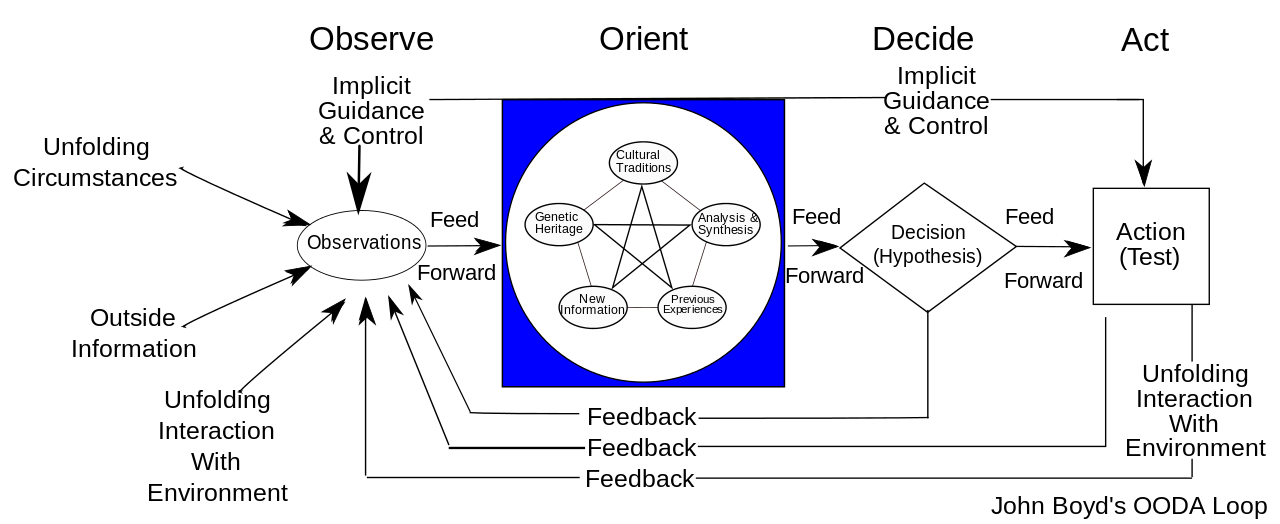

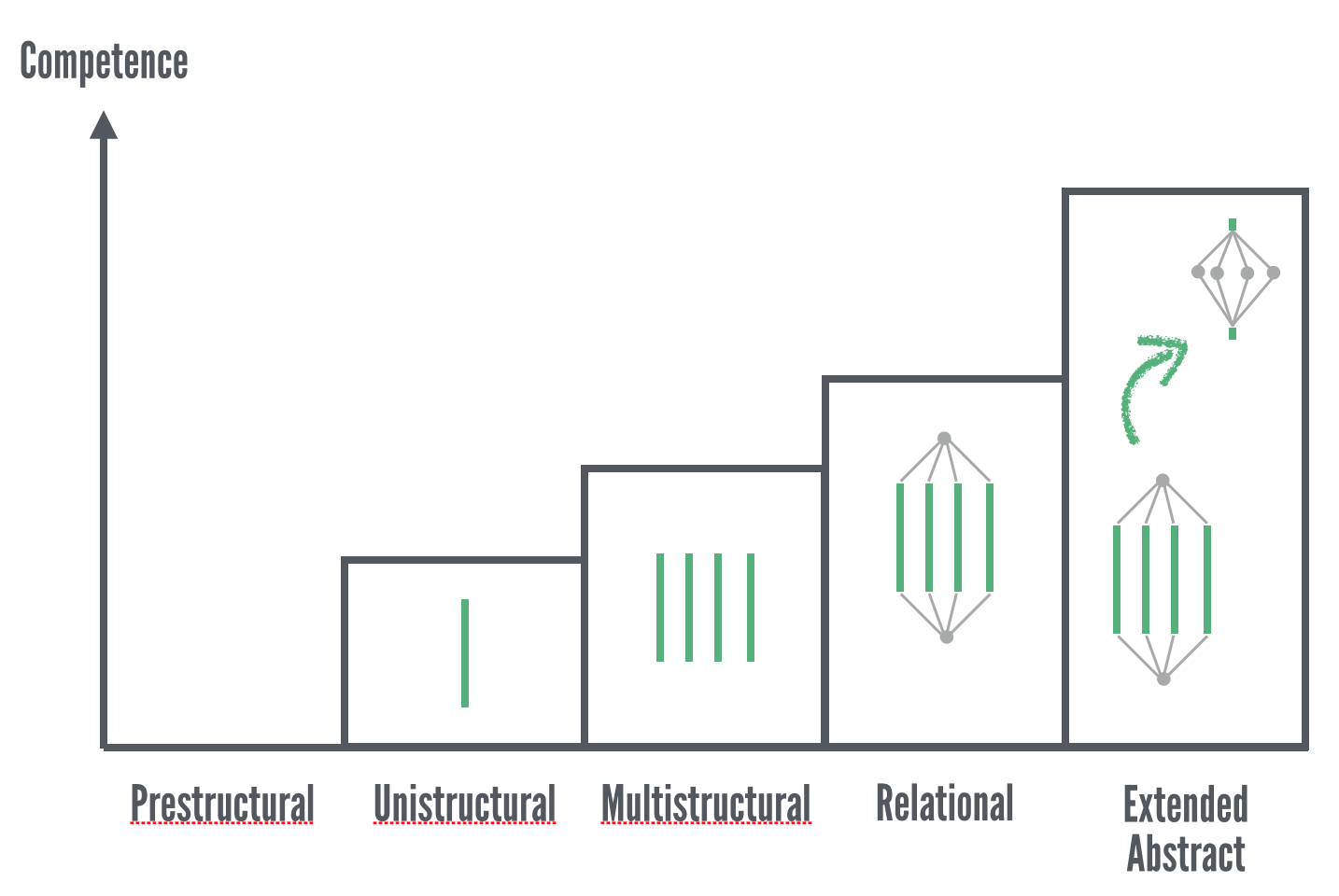

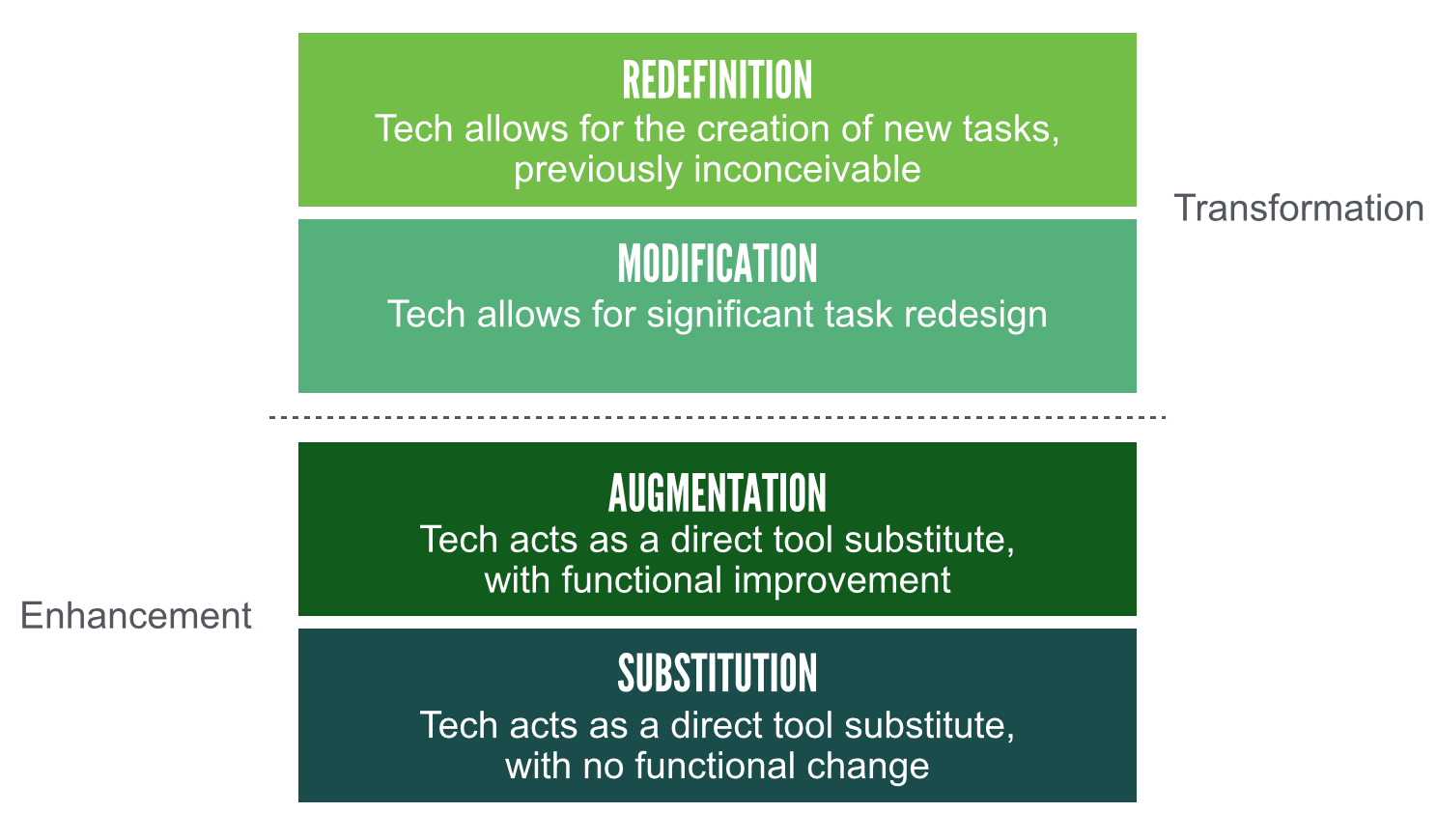

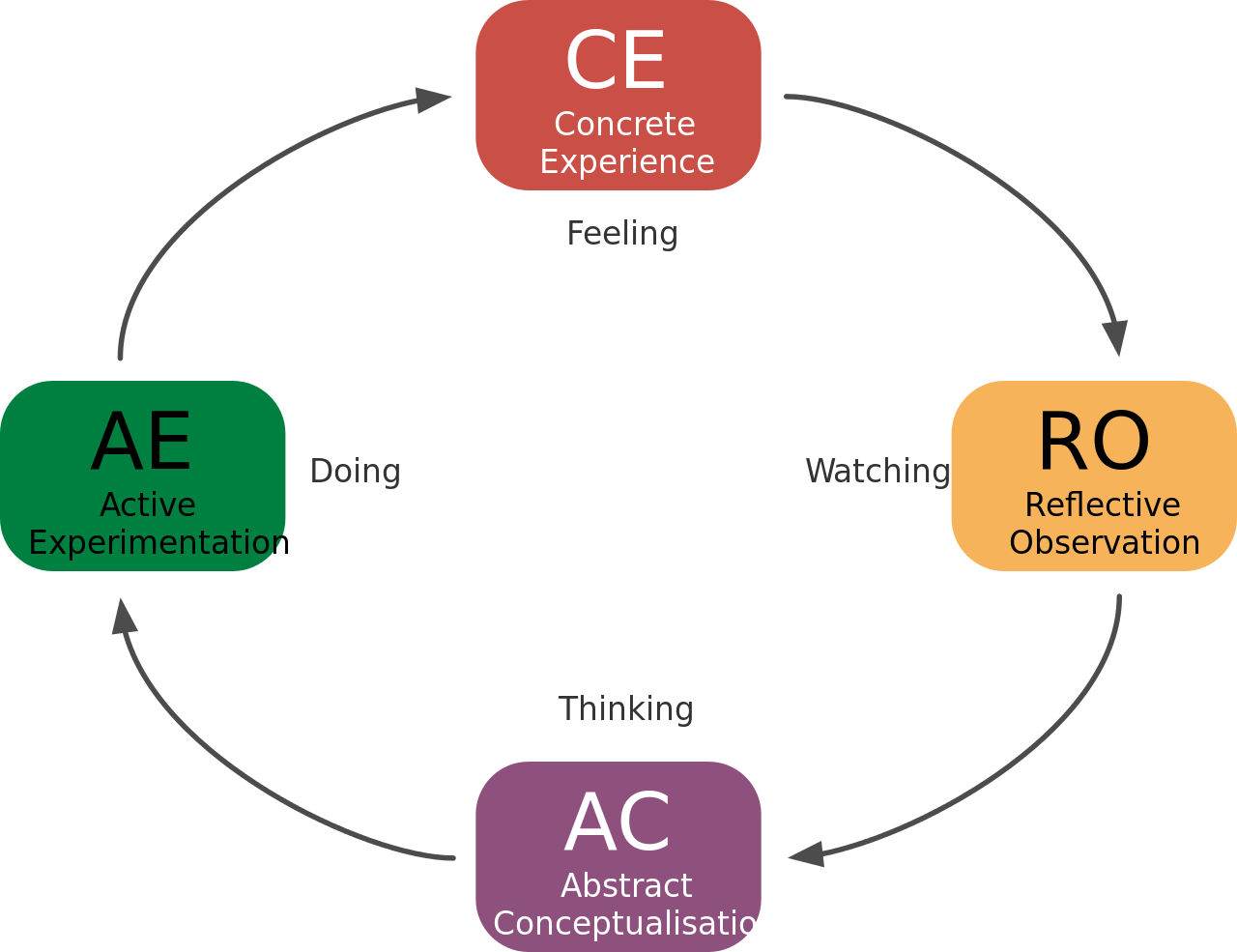

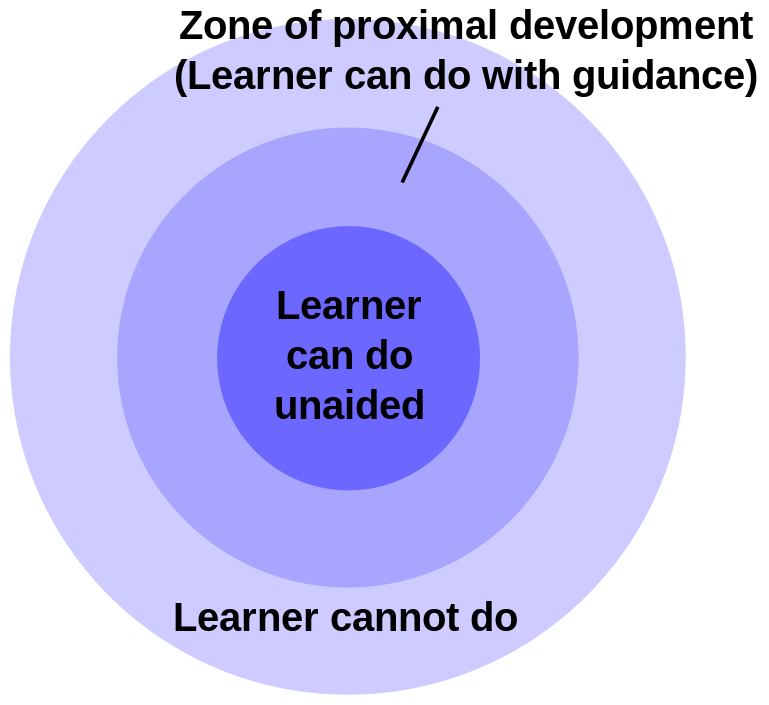

Well, a couple of things, I suppose. First, in relation to my 7 approaches to educational technology integration post, I feel like there’s some really easy ways to move staff up the SAMR model towards the ‘transformational’ type of technology use we want to see. One thing I’ve been focusing on recently, is explaining the mental models behind technologies. In other words, rather than telling people where to click, I’m explaining the concepts behind what it is there doing, as well as situations in which it might be helpful. How they teach is up to them; I’m providing them with skillsets and mindsets to give them more options.

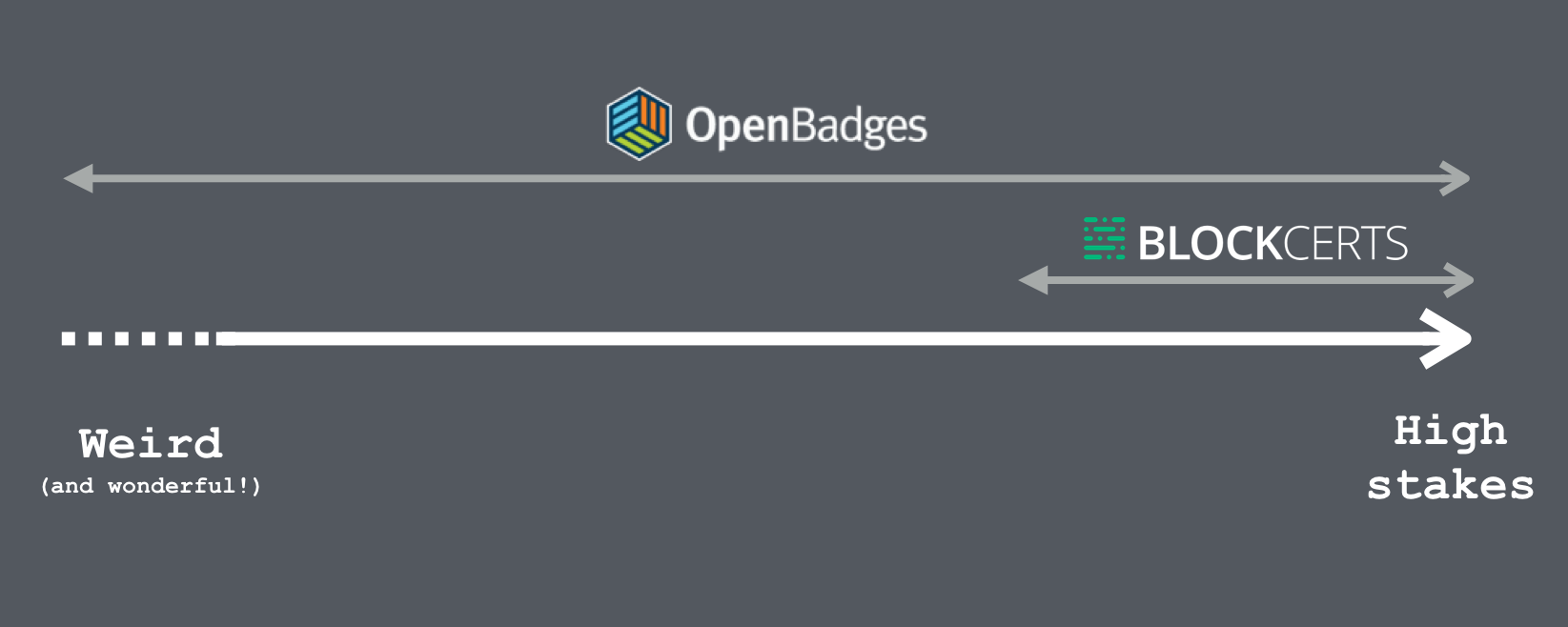

Second, I feel like there’s a huge opportunity to integrate Open Badges with G-Suite for Education. It seems pretty straightforward to build upon Google’s platform to provide the email addresses of who should be issued a badge, as well as the environment in which badge issuing would be triggered.

I’m thinking through a badging system for one of my clients at the moment, built upon the usual things I emphasise: non-linear pathways, individual choice, and an element of surprise. In that regard, I’m planning on starting with something like a ‘Classroom Convert’ badge that recognises that staff are developing mindsets around the use of Google Classroom, as well as skillsets.

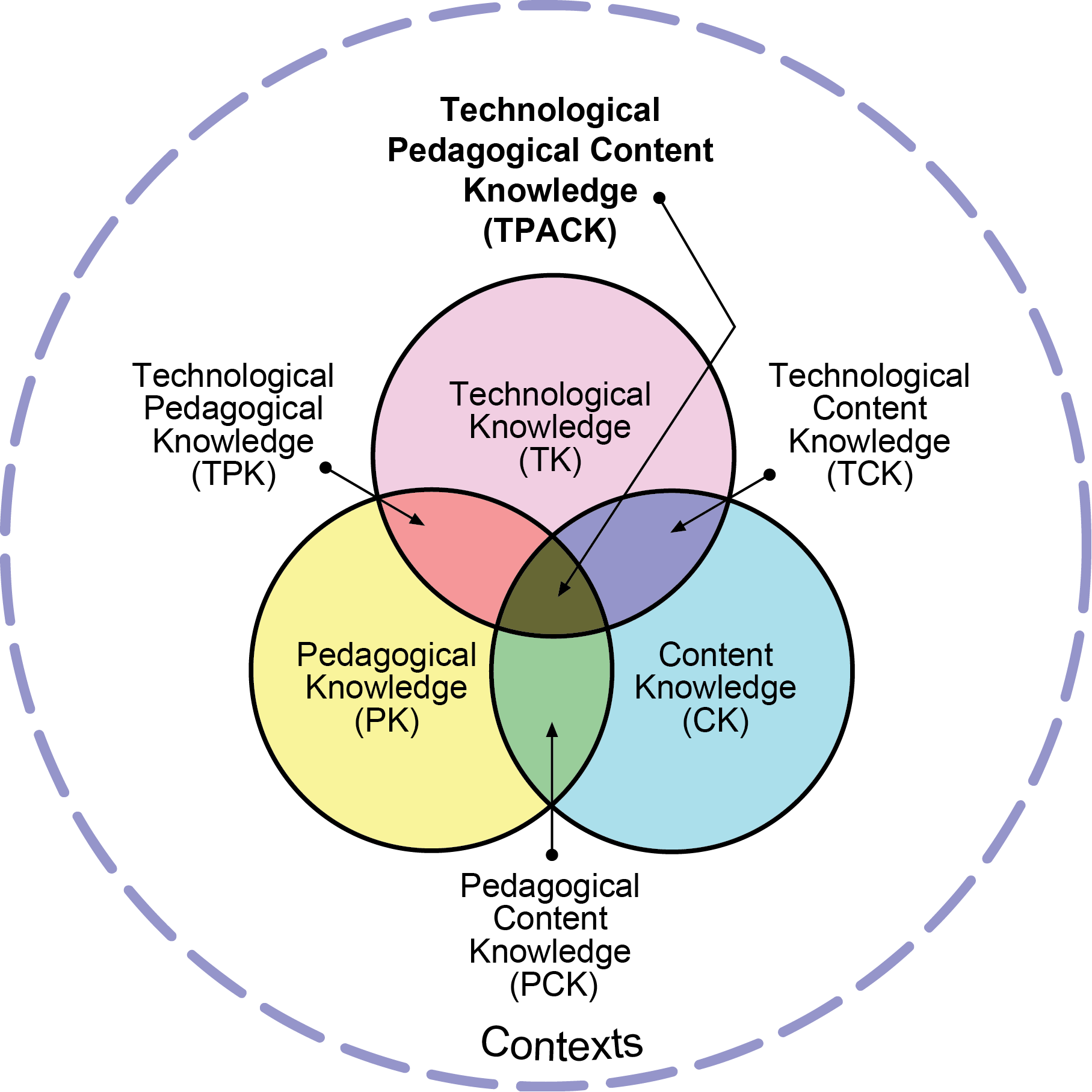

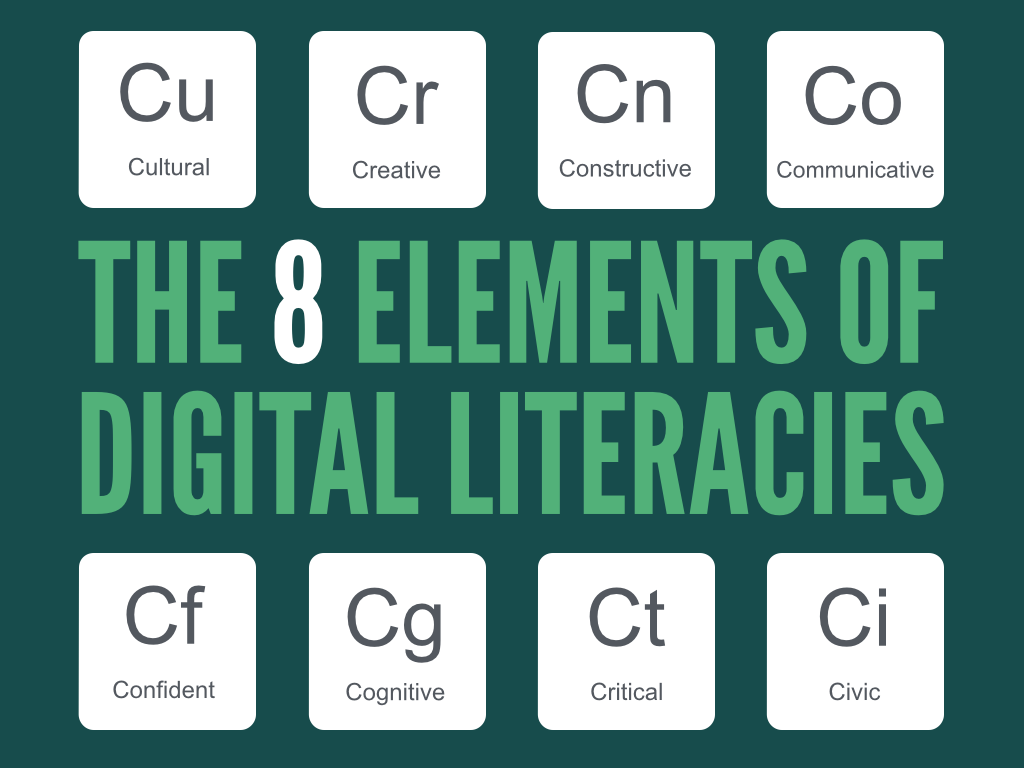

There are, of course, ways in which staff can go ‘full Google’ and become (as I am) a Google Certified Teacher, and so on. That’s not what this is. My aim in any badge system is to encourage particular types of knowledge, skills, and behaviours. Whatever system I come up with will be co-designed and go beyond just the use of G-Suite for Education. As the TPACK model emphasises, the system will have a more holistic focus: integrating the technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge required for purposeful educational technology integration.

Utopia

Ideally, I’d like an approach where students can use something like Unhosted apps to bring their own data store to the applications they choose to use when collaborating with their teachers and fellow students. I’d like to see them have a domain of their own, and learn enough code to have real agency in online digital spaces.

While I’ve got that in mind, I’m also a pragmatist. The tools Google provides through G-Suite for Education, while not world-changing, do move the Overton Window in terms of what’s possible in technology integration. Even just working collaboratively on a single Google Doc is pretty mindblowing to people who haven’t done this before.