Beyond the Textbook?

A couple of days ago I noticed #beyondthetextbook emerging on Twitter. It turns out that this hashtag related to an gathering sponsored by Discovery Education in Washington D.C.

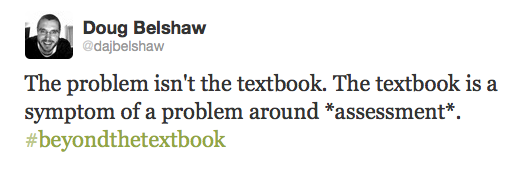

My (remote, somewhat helicopter-like) contribution, was pretty much summed up by the following:

After reading Audrey Watters’ post about the gathering (as well as those by others), I’d like to expand up on that and highlight some thoughts from others with whom I’m in agreement.

Trojan textbooks

I want us to weigh classroom practices, power, authority, politics, publishing, assessment, expertise, attribution, and the culture(s) of the education system. I would argue that the textbook in its current form — and frankly in almost all of the digital versions we’re also starting to see now — is tightly woven into that very fabric, and once we tug hard enough at the “textbook” thread, things come undone.

The textbook is easy to talk about. It’s a physical thing that people have known as students and, for some, as educators. The trouble is that, just as with any technology, it’s difficult to separate the thing from the practices that surround the thing.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with textbooks – especially if you define them as Bud Hunt does as “A collection of information organized around thoughtful principles intended to provide support to instruction.” I’m not so keen on the word ‘instruction’ (I’d substitute ‘learning’) but like his basis in ‘thoughtful principles’.

Getting assessment right

One of the reasons I’m such a big fan of badges for lifelong learning is that assessment is broken. I don’t mean ‘broken’ in the sense that a bit of a repair job would fix. I mean structurally unsound and falling apart. Liable to collapse at any moment. That kind of broken.

It’s a problem I felt as a classroom teacher. It’s an issue I had to deal with as a senior manager. It’s evident in my sector-wide role in Higher Education. The hoops through which we’re asking people to jump not only don’t mean anything any more, but they don’t necessarily lead anywhere.

To me, that constitutes a crisis of relevance. So when we’ve got textbooks solely focused on providing content in bite-sized chunks in order to allow people to pass summative tests, then we’ve got a problem. A huge problem.

But let’s be clear: the problem is to do with the high-stakes assessment. It’s akin to the current attacks on the efficacy of teachers. The problem isn’t with (most) teachers, it’s with what you’re asking them to do. Likewise, with textbooks, it’s not the collecting of information in one place – it’s what people are expected to do with that information.

Open content and the blank page

I’ve seen many state their belief that the best kind of textbook is the blank page. By that, they mean that textbooks should be co-constructed. I certainly can’t argue with that, but we must always be careful that we don’t substitute one form of top-down structure with another.

Back in 2006 I wrote a couple of posts on my old teaching blog. One covered the idea of teachers as lifeguards, and other focused on the teacher as DJ. In the former I talk about the importance of teachers ‘knowing the waters’ so that they can allow students to explore the waters, growing in confidence (but be there when things go wrong). In the latter I discuss the similarities between teachers and DJs around ‘tempo’ and ‘playlists’.

Both the lifeguard and DJ analogies work with textbooks, I think. The difficulties are always going to be around time and competency. It’s all very well for those new to the profession, willing to burn the candle at both ends to remix the curriculum and create their own textbooks to move #beyondthetextbook. But that’s a recipe for burnout.

Conclusion

As usual, I’ve more questions than answers, but if I have one contribution to the #beyondthetextbook debate it’s that our current use of textbooks is a symptom of the problem, not the problem itself. It’s difficult to debate nuanced things online, and even more so via Twitter.

I think we need a renaissance in blogging – and the kind of blogging where we reference other people’s work. If we’re going to debate problems in education, let’s do so at length, with some nuance, and in a considered way.

Thanks for reading this far. I’d love to read any comments you have below!

Spot on Doug. As long as we have an assessment regime that requires the ‘learning’ of information, then the text book (however interactive it is) is going to be a symptom. If you measure teachers on exam results, then guess what, teachers will try to improve what they are measured on. If we want a shift in education we need to change what is measured. I suggest a movement towards ipsative assessment rather than summative.

Indeed – which is another reason why need a debate about the purpose(s) of education!

http://purposed.org.uk

I’ll be referencing this post in my next post (I’ll send out a link on twitter) because I like the questions it brings up. And, as you said, we need to have true discourse on the topic of textbooks. It seemed to me that what was lost in all of the tweets on Monday was the fact that textbooks are just another resource. We should not consider them as anything more or less. There are better resources and there are worse resources. As a teacher it is my responsibility to teach my students to evaluate the resources they decide to utilize in their learning. If a student loves the feel of a book in his or her hands and loves to turn the pages and see the flow of material as it is presented in the written form then that might just be the best resource that student can find on a particular subject. If, on the other hand, a textbook is seen as a harbinger of disaster (for some reason) then no matter how great the content is in that book the student will not glean any knowledge from that source.

Too often people want to bash textbooks when the actually want to bash things associated with textbooks, such as assessment. As you stated. Nice post.

Thanks Chris – I look forward to reading your post. 🙂

“The hoops through which we’re asking people to jump not only don’t mean anything any more, but they don’t necessarily lead anywhere.”

An interesting opinion which has some resonance with me, but I’m not sure I’d 100% agree . I think it might be more accurate to say that the ‘hoops’ don’t mean anything (are not relevant) to SOME people, and are not an appropriate path for SOME people. This appears to me to becoming truer in the UK at least at school level with the narrowing of the 14-19 curriculum currently being pushed. I would really like to see some hard evidence to support the certaincy in your remarks – can you point me in the right direction?

I’d agree that focussing on text books is irrelevant. And also that the ‘digital’ text books being promoted by the major educational publishers are just depressing (the only advantage over paper seems to be that they’re harder to lose and dont wear out; on the flip side you need a device costing at least £100 and an internet connection to read them).

I think the challenge for educators (and I speak from a background in secondary education) is to make our voice relevant in the current political context in the UK. When there is so much to object about (curriculum change, pensions, etc) its hard to present a positive voice, and the ‘professional associations’ only seem to make matters worse.

Totally agree with your remarks re. debating on Twitter. In fact a major gripe of mine. If only I had the time/commitment to take part in a blogging renaissance!

Hi Andy, thanks for the comment. 🙂

I agree with your provisos and I certainly haven’t got any ‘hard evidence’ (not would I necessarily know it when I saw it!)

I know where you’re coming from regarding the ‘£100 device’ comment. Instead of trotting out the familiar argument that these are getting cheaper all the time, let me try a different tack.

If (and only if) devices are being used at the same time as, say, a concerted drive to reduce the amount of paper/photocopying used within an institution, then there’s some of your savings. Couple that with a reduction in the number of paper-based textbooks and you might actually be *better* off with tablets! (Look at Essa Academy as an example of this.)

Thanks for taking the time to reply.

ESSA is an interesting example where they have started with the big picture – designed a curriculum to support the learners (modular, stage not age), a flexible assessment system (at least within the constraints of recognised qualifications), and quite a radical pastoral system (e.g. every adult in school is a form tutor). The use of technology is integral to supporting this, and certainly seems to have helped them achieve their goals. The ‘paperless’ school almost a necessity to make it affordable, but seems to show it can be done, and with some significant cost savings.

Might be interested to know in Denmark they allow (or at least, were piloting) the use of the internet in a number of school-leaver exams – looks like a v. different conceptualisation of knowledge to many other places. Nice video on it here: http://vimeo.com/8889340

Conrad Wolfram also delivered a nice talk at Learning Without Frontiers on teaching computation (arithmetic, rote learning, etc.) versus programming (creativity, access to calculators, etc.) http://www.learningwithoutfrontiers.com/2012/02/conrad-wolfram-making-maths-beautiful/

Big area of interest to me in terms of what it means to “know” and assess knowledge, and the place of external artefacts (textbooks, internet, calculators, pen & paper, etc.) in that 🙂

Thanks for the links Simon! Knew about tge Denmark plans and saw Conrad at Thinking Digital last year. Managed to miss him at LWF unfortunately!

Textbooks aren’t really that big in Australian primary schools – they are mostly purchased as a teacher resource and photocopied (breaching copyright in a major way) strategically to create student worksheets but having class sets in a primary school classroom is very rare. I did see a class set purchased by a teacher recently and your quote brought that back to me – the textbook is also a symptom of the problem of teacher knowledge and / or confidence (or lack of) in covering the set curriculum. And one could also add that the textbook is a symptom of a problem around pedagogy. FWIW.