After being away for a couple of weeks in Australia and the USA, I’m back home. It’s time, therefore, to finish off the Futurelearn course I started around Understanding the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

It’s a four-week course, and I’ve written about what I’ve learned over the past three weeks’ worth of material in the following posts:

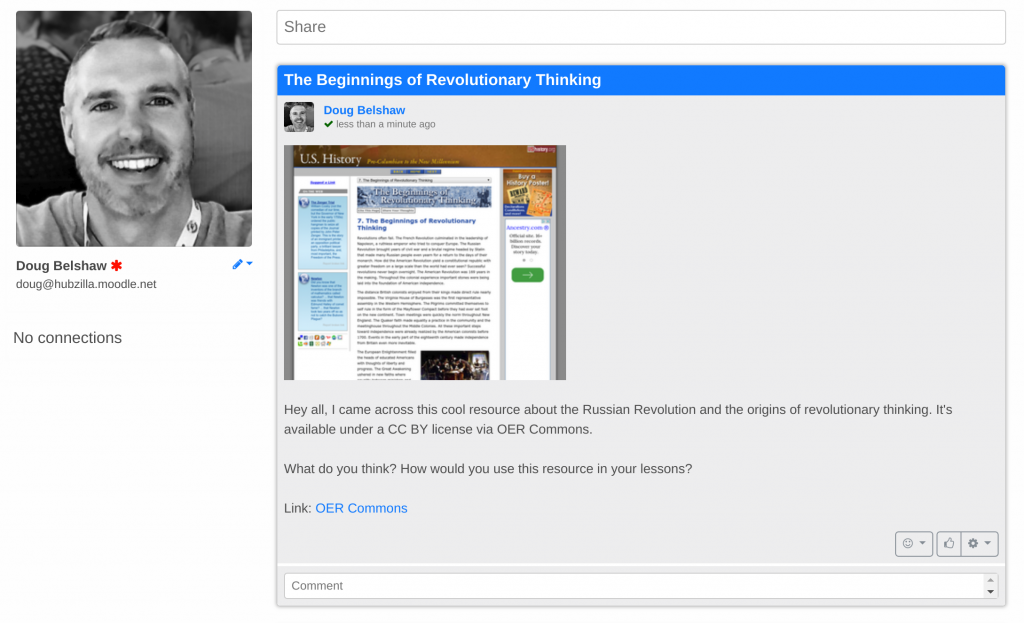

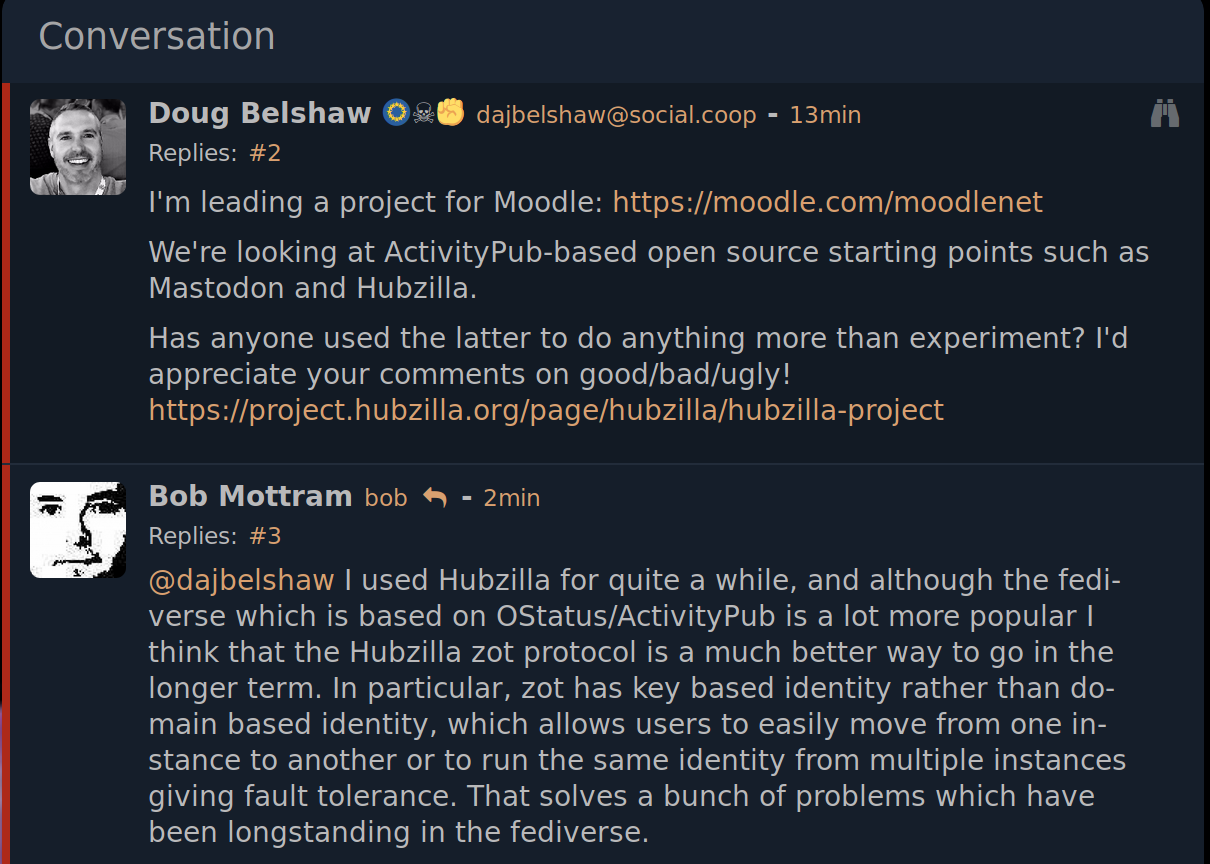

What follows, therefore, is about the final week — entitled ‘Responsibilities, liabilities and penalties’. I’m digging into in this area because I’m leading the MoodleNet project. However, I’m writing here instead of on the project blog as I’m still coming to grips with all that GDPR means in practice.

I like the way that the course organisers frame the final section of this course:

As individuals or natural persons, you should know that most of the activities that you daily perform, all the forms that you are asked to fill in and most of the technology that you use on a daily basis leave a trail of personal data behind. Collecting data, analysing and linking different databases create the possibility to learn very personal information about you and obtain details about your life and life of those who you care about. More than you would have ever thought. More than you even remember. To give but one example: 4 pictures of you placed on the Internet allow facial recognition programs to find you again when crossing the street. Given this situation, you need protection.

Supervisory bodies

As per the title of this week’s course title, the focus is all about how GDPR will be enforced:

These enforcement mechanisms include a number of measures and instruments:

- The establishment of national supervisory authorities (and the Lead Supervisory Authority in case of cross-border data transfers) and of the European Data Protection Board (Chapter 6);

- Arrangements to streamline legal compliance, including codes of conduct (Article 40), data protection certifications (Article 42), binding corporate rules (Article 47) and standard (contractual) data protection clauses (Article 46);

- Rights of data subjects, including the right to lodge a complaint and the right to an effective judicial remedy (Chapter VIII);

- A multi-layered mechanism to protect the transfer of personal data of EU citizens outside the EU (Chapter V);

- Liabilities and sanctions for violation of laws (Chapter VIII);

- The role of Member States in compliance and implementation.

The EU provides a way to ensure local colour and context is respected, while enforcing a European-wide framework. The aim is to prevent safe havens for bad actors:

Each national supervisory authority is empowered to monitor any data processing activity that takes place within its territory (jurisdiction). It is also charged with the task to monitor any data processing activities that target data subjects residing in its territory, even in those situations where the activities are carried out by non-EU data controllers or processors. However, since in an online environment data does not always respect borders, the territorial jurisdiction of a national supervisory authority is not always clear cut.

As a result:

For avoiding situations in which more than one national supervisory authority are competent, the GDPR has introduced the legal concept of the lead supervisory authority or LSA.

When national supervisory authorities realise that a case brought before them has a cross-border dimension… they refer the case to the LSA which decides if it will handle the case or not within three weeks. Article 56 GDPR provides that the lead supervisory authority for cross-border processing of data will be the authority that is competent to supervise the entity engaged in data processing of individuals in different countries or, the authority competent to supervise the main establishment of the data controller or processor in case this has different establishments in several Member States.

So taking the example of the UK (where I live) there’s a national supervisory authority which is then subject to the lead supervisory authority. That, in turn, is subject to the European Data Protection Board:

To ensure the consistent application of the GDPR throughout the EU an important role will be played by the European Data Protection Board (the Board).

Even though the denomination looks new, the Board in itself is the continuation of the existing Article 29 Working Party which was established under the old Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC.

[…]

The old Article 29 Working Party was often criticised for not adequately consulting stakeholders before taking decisions. In reaction to this criticism, the Board is required to consult interested parties where appropriate. This would of course benefit data controllers or processors that might be affected by the decisions adopted.

So it sounds like the EU have learned their lesson:

Similarly with the Article 29 Working Party, the Board is composed of the heads of national supervisory authorities and the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS), or their representatives. The EDPS’s voting powers are restricted to those decisions that would be applicable to the EU institutions.

The Board also includes a representative of the European Commission who, however, does not have a right to vote so as to ensure the independence of the Board. There seems to be an implicit suggestion that the European Commission has exercised too much influence over the Article 29 Working Party in the past and the GDPR wants to ensure that this will not be the case in the future.

There’s some great provisions in the GDPR but I have to wonder just how quickly some of the decisions and actions will be taken:

Together with the establishment of the Lead Supervisory Authority presented in the previous step, the consistency mechanism is intended to avoid such situations. When it is clear that the decision of a supervisory authority will have an EU-wide impact, or when a request comes from a national supervisory authority, the Chair of the European Data Protection Board or from the European Commission, the Board issues a non-binding decision on a specific case. The national supervisory authority dealing with the case shall take utmost account of the decision of the Board or shall inform the Board in the case in which it does not intend to follow its opinion.

Codes of conduct

Part of any compliance system involves self-regulation, and the GDPR is no different. I like the ‘code of conduct’ approach in this regard:

For controllers and processors, codes of conduct are an important tool for achieving legal compliance and creating evidence to support this. Member states’ supervisory authorities, the board, and the commission encourage drafting codes of conduct. Such codes of conduct can be prepared, amended, or extended by associations and other bodies representing categories of controllers and processors. Codes of conduct need to include measures specifying the application of the GDPR, This includes, for example, the collection and pseudonymisation of personal data, exercise of data subjects’ rights, and notification of a data breach. Codes of conduct contain mechanisms that enable supervisory authorities to carry out mandatory monitoring of compliance. Drafts, amendments, or extensions of codes of conduct need to be submitted to the supervisory authority for approval.

Companies and other organisations have to ‘walk the walk’, though, and not just have their documentation in place:

Apart from supervisory authorities, other competent bodies with an appropriate level of expertise and accreditation can also monitor compliance with codes of conduct. Drafting codes of conduct is one thing. Committing to them is another. It is important in the sense that it can provide evidence that controllers and processors comply with the GDPR. This not only counts for controllers and processors within the EU, but also for those who are not subject to the GDPR in order to provide appropriate data protection safeguards.

Binding corporate rules

One way of moving beyond a code of conduct is for large, multi-national organisations to implement ‘binding corporate rules’:

Binding corporate rules (BCRs) are internal rules adopted by multinational groups of companies. They define the group’s global policy with regard to the international transfers of personal data to companies within the same group that are located in countries which do not provide an adequate level of protection. They are legally binding and approved by the competent supervisory authority in accordance with the consistency mechanism.

These rules are beneficial for the organisation (efficiency / consistency), for the EU (compliance) and for the end user (transparency).

The GDPR allows for personal data to be transferred outside the EU, but not just anywhere:

As a general rule, transfers of personal data to countries outside the European Economic Area may take place if these countries are deemed to ensure an adequate level of data protection.

Article 45 GDPR provides that the third countries’ level of personal data protection is assessed by the European Commission. According to the GDPR, the Commission’s adequacy decision may be limited also to specific territories or to more specific sectors within a country. A current list of countries that have been evaluated as having an adequate level of data protection can be found here.

The example given in the course is of Japan, which isn’t currently listed as having adequate protections. However:

Personal data can be transferred to a third country even in the absence of an adequacy decision:

(i) if the controller or processor exporting the data has himself provided for appropriate safeguards; and

(ii) on the condition that enforceable data subject rights and effective legal remedies are available in the given country.

At the end of the day, it’s the organisation’s responsibility as the data controller to comply wih the GDPR:

In accordance with the provisions in Chapter VIII, controllers and processors are legally liable for damages caused by data processing activities which infringe the GDPR. A controller is liable for all damages caused by processing activities. A processor is liable for not complying with its obligations or for acting outside or contrary to lawful instructions of a controller. A data subject who has suffered material or non-material damages as a result of a violation of the GDPR has the right to receive compensation for damages…

Fines

So now we get to the interesting part. What can the EU actually do about GDPR infringement?

According to Article 83 GDPR, the fines may, depending on the infringed provision of the GDPR, amount to a maximum of 20 million Euros, or, if this is a higher amount, to 4% of the total worldwide annual turnover of an undertaking. For example, a failure to implement the data protection by design and by default is subject to a maximum fine of only 10 million Euros or 2% of the total worldwide annual turnover of an undertaking. On the other hand, violating the basic principles of data processing, including the conditions for obtaining a valid consent as well as non-compliance with a supervisory authority’s order may result in the highest fine of 20 million Euros or 4% of the total worldwide annual turnover.

That’s obviously a lot of money, but it’s a sliding scale:

What the amount of a fine will be at the end will depend on the nature, gravity and duration of the infringement as well as on its character – if there was intention or negligence from the undertaking. The supervisory authority must ensure that the administrative fines would be in each specific case proportionate to the infringement and at the same time also effective and dissuasive. As a result, not all infringements of the GDPR will lead to those serious fines mentioned above.

The good thing, however, is that the fines are calculated on global revenues, rather than just the amount the organisation makes in the EU:

Once the GDPR becomes applicable, the impact of a fine on data controllers and processors, even if not reaching the maximum amount established in Article 83 GDPR, could be significant. Also, in those situations in which a global organisation has only a small establishment in the territory of the European Union, or is completely based in third countries but it targets the processing of personal data of EU citizens, the fine would be based on the total worldwide annual turnover. Thus, following the data protection rules as established by the GDPR should be taken seriously both by EU and foreign organisations.

Conclusion

I’m hopeful that the GDPR is going to help the legal system catch up with some of the technology that’s permeated our lives over the last couple of decades. Time will tell, of course…

Image by the Latvian State Chancellery used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license