A quick dive into ALT’s journal with my MoodleNet hat on

One of the things I miss from my doctoral research is reading journal articles. So, with my MoodleNet hat on, I dived into ALT’s Research in Learning Technology today. I was on the lookout for things related to professional development and Open Educational Resources (OER).

Drumm, L. (2019). Folk pedagogies and pseudo-theories: how lecturers rationalise their digital teaching. Research in Learning Technology, 27. https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v27.2094

I admit that I was attracted to this article by its title, but it came up trumps:

Ideally, educators should critique and adapt ‘best practices’, taking charge of their own pathways of teaching. Indeed, as demonstrated in the data, many of these lecturers do this, but there is a block in articulating, reflecting and sharing these pathways. A solution could be to frame academic development and teaching qualifications as a medium for educators to explore their own voices and communicate about their teaching, without requiring them to fit into prescribed orthodoxies. Rather than setting folk pedagogies and pseudo-theories as ‘incorrect’, they could be acknowledged and used as starting points for conversations about teaching.

Macià, M., & García, I. (2018). Professional development of teachers acting as bridges in online social networks. Research in Learning Technology, 26. https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v26.2057

This is a particularly useful paper, where the author refers to ‘social networking sites’ as ‘SNSs’. It’s worth quoting at length:

SNSs used in education can promote socioconstructivist learning (Allen 2012; Manca and Ranieri 2017) by modifying the learners’ role and providing them with new educational understandings. The interconnected model of professional growth explains how teachers can benefit from the information acquired in online SNSs. This model takes several domains of the teaching situation into account (Clarke and Hollingsworth 2002): (1) the personal domain, including teachers’ ideas, knowledge and beliefs; (2) the external domain, represented by information or resources that teachers acquire while collaborating with other teachers or participating in training activities; (3) the domain of practice, related to action research activities developed in the classroom context; and (4) the domain of consequence, which includes students’ results and other consequences in the classroom climate or organisation. According to the interconnected model, an external source of information, which could be the consequence of participation in an online network or community, can generate change in teachers’ knowledge and foster new practices in their teaching. After experimenting in the classroom, teachers can evaluate the applied processes and student outcomes and, based on the results of this evaluation, make changes at a cognitive and behavioural level. In this context of participatory networking, teachers assume responsibility for the information that they exchange and the contributions they make to the educational networks in which they participate, as well as for the information they integrate and the connections they make, deciding by themselves what they need at every moment.

Recent research describes online teachers’ networks through the theories on social capital and social network analysis, which reveal how information flows between a group of network members (Ranieri, Manca, and Fini 2012; Schlager et al. 2009; Smith Risser 2013; Tseng and Kuo 2014). Bordieu’s ‘social capital theory’ (1986) asserts that:

the social capital possessed by a person depends on the size of the network of connections they can effectively mobilize and on the volume of the capital (economic, cultural or symbolic) possessed in their own right by each of those to whom they are connected. (p. 21)

Then, teachers’ social capital can increase when they connect to a larger number of colleagues who are highly skilled. According to Bordieu (1986), participants in a group have to make an effort to sustain the relations that ensure the continuity of the social formation through social exchanges. These social exchanges are identified as mutual recognition and recognition of the membership and also define the limits of the group. Members control new entries by defining occasions, places or practices to gather with other people who have similar interests. In this sense, maintaining and increasing social capital through exchanges requires continuous efforts of sociability, recognition and social competence, and this can result in the transformation of one’s own cultural capital (knowledge, principles and values).

Twitter is of special interest for this research because many teachers participate in this network and use it to share experiences and reflect on practice, to pose or ask questions, to share teaching materials and resources, to hold generic discussions and to provide emotional support (Davis 2015; Smith Risser 2013; Wesely 2013). In general, people tend to use Twitter to write posts about themselves, whereas educators tend to use it to share information (Forte, Humphreys, and Park 2012). For this reason, Twitter frequently plays the role of an aggregator of content or resources present in other social networks or virtual sites (Wesely 2013), as teachers tweet the link to such content and it can be recovered through the use of a hashtag (the method used on Twitter to categorise tweets into topics). Teachers also use Facebook, especially the ‘groups’ functionality, which is a closed environment that facilitates interchange around generic or specific topics (Ranieri, Manca, and Fini 2012). The use of both networks may have an impact on teachers’ professional growth by fostering their digital competence and helping to change their practice and educational perspectives (Manca and Ranieri 2017).

This quotation from an interview with a teacher is illuminating:

Starting to share in networks for me was a ‘before and after’. It was a complete change. I have evolved as teacher and I have a relationship with students which I never imagined. It has been much more than the knowledge, new tools or meeting people; it has generated a change in the way I work. After the project [a project about student talents] I started to take into account students’ emotions. I learned to respect students. (Interview, Teacher 6)

Also useful:

The teachers interviewed were all active members on SNS and preferred Twitter for dealing with educational issues. Twitter is a generic SNS that has been adopted by educators for multiple professional purposes such as communicating with others, increasing the visibility of classroom activities and sharing information, resources and materials (Carpenter and Krutka 2014, 2015; Davis 2015; Veletsianos 2012; Wesely 2013). The asynchronous nature of online SNSs, the knowledge sharing and the immediacy of responses make Twitter and other SNS a suitable space for enhancing teacher professional development. Twitter was also praised for filtering valuable content for teachers, for facilitating searches on educational topics (Carpenter and Krutka 2015) and also for enabling serendipitous learning thanks to its condition of being a network (Wenger Trayner, and de Laat 2011). The participants in the study justified that they used Twitter because of the rapid flow of information, the ease of use of the platform, its open and participative nature and finally the high number of Twitter users who belong to the educational world. Indeed, involvement in online SNS helps teachers enlarge their professional community, share resources and reflect on teaching practices (Carpenter and Krutka 2014, 2015; Wesely 2013).

Participant teachers also used instant messaging applications such as WhatsApp or Telegram to keep in touch with other teachers or to sustain active discussion groups. The use of these tools is very much related to mobile phones. These tools offer the same immediacy as Twitter in a closed and more controlled environment, where people can only join by invitation. The use of these instant messaging tools, and particularly their use in combination with other SNSs, has barely been studied for educational and training purposes but could be effective for maintaining informal communities of teachers (Bouhnik and Deshen 2014; Cansoy 2017).

The activities conducted openly in this SNS are mainly sharing information and socialising. In fact, we can consider that these two types of activities determine two different patterns of participation: (1) teachers who mainly use Twitter to share information, news, resources or media and who dedicate around two-thirds of their activity to this endeavour, and (2) teachers who mainly use Twitter for social purposes such as living a social life, live event participation and courtesy, with this social activity accounting for around 50% of their total activity. These two patterns, consisting of sharing information or being social, could be related to teachers’ interests and also to their personal and professional identity. Carpenter and Krutka (2014), in a study with 755 educators, found that the 96% of them used Twitter to share and acquire resources, 86% to collaborate with other teachers, 76% for networking and 73% for chatting. These results are consistent with the two main patterns of Twitter use identified in this study.

This explorative study into teachers who act as bridges reveals that they are active in SNSs and that they take advantage of this participation by introducing new practices into their classrooms and also by collaborating with other teachers to develop school practices. These teachers are highly motivated, enjoy their work and are eager to improve professionally, which could have triggered their participation in SNSs. Thus, it is not clear whether their participation in SNSs directly causes the improvement in their teaching practices or whether SNSs are just another tool used by teachers who are already interested. This question remains open and it is key to understanding the role that online networks and communities can play in teachers’ professional development. Our results show that there is certain interdependence between actively participating in an SNS and being involved in several communities. The results also highlight the relevance of lightweight peer production and peripheral participation in productive online social networks, which materialises in this bridging role that certain participants assume.

Atenas, J., & Havemann, L. (2014). Questions of quality in repositories of open educational resources: a literature review. Research in Learning Technology, 22. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v22.20889

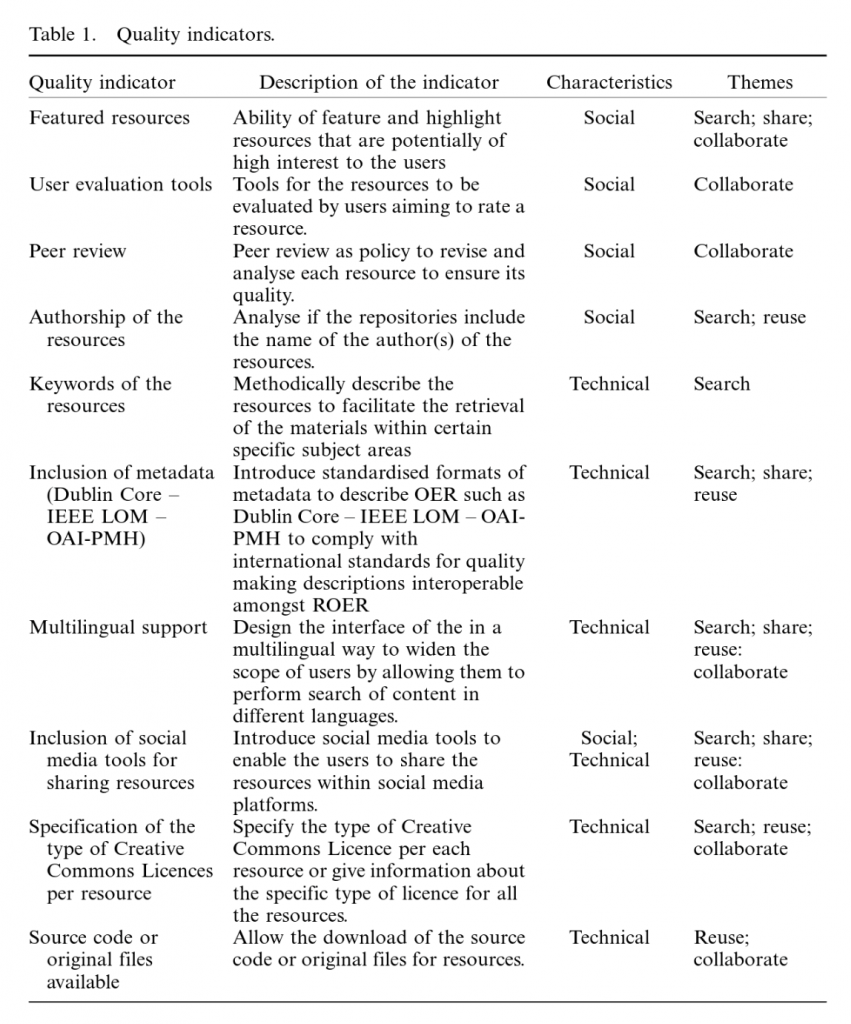

This paper is all about ‘quality indicators’ in Repositories of OER (ROER):

Drawing from our analysis of the literature, we would argue that the ethos underlying the creation of ROER can be said to comprise four key themes, which we refer to as Search, Share, Reuse, and Collaborate. The purpose of ROER is to support educators in searching for content, sharing their own resources, reusing and evaluating materials, and adapting materials made by or in collaboration with other members of the community.

The four themes can be understood in greater detail as follows:

- Search: As Google tends to be the first reference point for many people, it can be considered a ‘living index and repository for enormous content’ (Atkins, Brown, and Hammond 2007). Although the internet has among its archives billions of documents and multimedia materials that can be found by using search engines, it is a more complex task to ensure that the materials and documentation discovered in such searches are appropriate to a specific educational field and context. For Wang and Hwang (2004), it is difficult for educators to build and maintain personal collections and is ‘very time consuming to locate and retrieve distributed learning materials’. For Rolfe (2012), searching for OER in repositories facilitates the non-commercial reuse of content with minimal restrictions.

- Share: According to Hylén (2006) one of the possible positive effects of openly sharing educational resources is that free trade fosters the dissemination of knowledge more widely and quickly, so more people can access resources to solve their problems. For Windle et al. (2010) the quality assurance and good design of OER can enhance the reuse and sharing of OER, as ‘evidence suggests that those who feel empowered to reuse are more likely to themselves to share and vice versa’ (p. 16). According to Pegler (2012), if OER are not shared or reused, the main objective of the OER cannot be accomplished; also, the number of times in which a resource has been shared can be considered a measure of resource quality, as it provides an indication of the impact a particular resource has had.

- Reuse: A key concern of educators regarding the reuse of OER relates to the contextualisation of resources; to adapt, translate or reuse materials for use in different socio-cultural contexts could potentially be more difficult or costly than creating new resources. To alleviate these challenges, the main impetus must come not from technologies but from pedagogical communities where academics and teachers are both, content producers and users (Petrides and Nguyen 2008). The practice of reusing content has in the past been considered ‘a sign of weakness’ by the academic community, but this point of view has been changing as the OER movement is increasingly embraced by academics which are willing to share their content with others (Weller 2010).

- Collaborate: OER repositories, if well designed, can serve to facilitate different communities of users who collaborate in evaluating and reusing content and co-creating new materials by encouraging the discussion around improvement of resources (Petrides and Nguyen 2008). Though traditionally teaching materials were produced within the context of a classroom, OER can be created collaboratively in virtual spaces (McAndrew, Scanlon, and Clow 2012). ROER have potential as a framework in which ‘various types of stakeholders are able to interact, collaborate, create and use materials and processes’ (Butcher, Kanwar, and Uvalić-Trumbić 2011).

Whitworth, A., Garnett, F., & Pearson, D. (2012). Aggregate-then-Curate: how digital learning champions help communities nurture online content. Research in Learning Technology, 20. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v20i0.18677

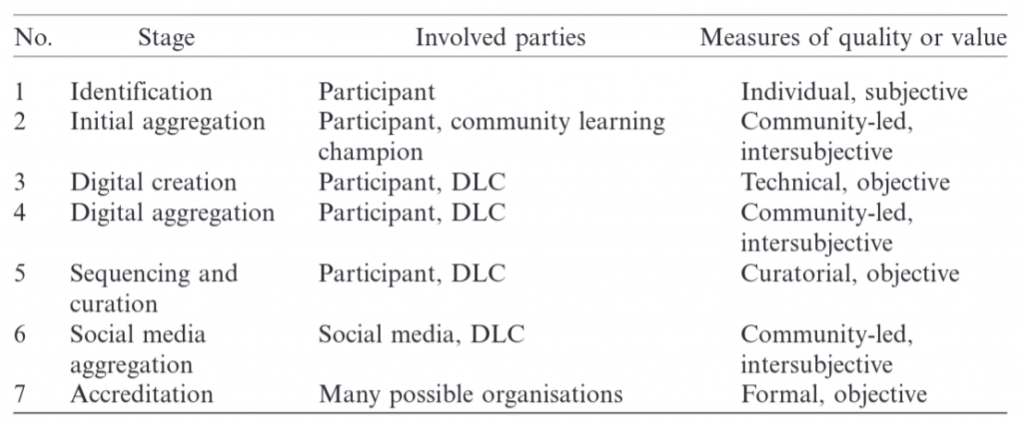

The authors refer to the ‘Aggregate-then-Curate’ model as ‘A/C’ and ‘Digital Learning Champions’ as ‘DLCs’

(1) Identification: The initial motivation for creating resources must come from the community participant (an individual, or a group), even if the motivation is in response to an external stimulus, e.g. a request to participate in a project. There will be at least one existing resource that the participant has in mind. This may be a physical object, a text (digital or otherwise), or tacit knowledge such as a skill, personal narrative, etc. The resource belongs to the participant and not to the project or to the partner institutions.

(2) Initial aggregation: This stage begins the process of connecting together resources by revealing links between them, suggesting appropriate groupings, potential learning pathways and so on. This is a social process and so must involve other members of the community, but not necessarily involve digital media. Often, it will take place very informally, as community members validate one another’s opinions about what information is useful, sometimes explicitly but often with reference to implicitly held, shared views – the sort of thing that binds people together in “communities” in the first place. However, it may also involve more organised and/or formal processes. What this stage entails is the intersubjective validation of initial, subjective ideas by members of the community.

(3) Digital creation: Once resources and connections between them have been identified by the community, some form of digital representation can be created. Even where some existing resources, first identified then aggregated in Stages 1–2, are already in digital form, the connections between them may need expressing as digital content in their own right.

A DLC would help here if they were at a different “developmental phase” in their work with, and experience of ICT, and could thereby provide technical assistance to the creation of digital artefacts. A particular resource might be very relevant and timely. However, its usefulness will be diminished if it is, for example, an inaudible recording. Is metadata in place, can the resource therefore be found by others? Is the appropriate format, or medium, being exploited? Is the material legal? These are more objective filtering criteria than apply at earlier stages.

(4) Digital aggregation: At this stage, resources are informally aggregated in a community-driven way. Digital aggregation involves using social links that either already exist (and may, or may not, have played a role in the initial aggregation at Stage 2), or which are discovered at the digital creation stage. Once again, this process may be supported by a DLC.

(5) Sequencing and curation: Sequencing is when the aggregation process takes on a more structured form. The collection of resources begins to demonstrate its potential to solve problems or drive learning outcomes both within and outside the community. Learning pathways or other broader narratives begin to be addressed through the aggregation process in a coherent way.

This is the stage at which curation comes into play. The subjective and intersubjective values assigned to the community informational resources by individuals and other community members, are validated here by interests that are partly external. This is a significant moment for the collection. If “curator” is broadly defined as “a person in charge of something … a guardian” (from Chambers English Dictionary), curation can therefore be defined as the management of a collection of resources at a fundamental level. As Simon (2010) recognises, and as our background discussion concluded, it is the level of participation in curation that is significant. Sequencing is the stage at which the resources’ quality begins to be judged by institutions that may still be familiar with the general context from which they emerged, but which are essentially external to the community. The role of a DLC here would be to facilitate the interaction across the boundary for mutual benefit, helping the community members reflect on, and thereby learn from, the interaction: but also helping the institution learn from the community.

(6) Social media aggregation: Their quality validated by a wide range of interests that remain local, resources that reach a certain standard – judged either by technical quality, informational quality, or widespread relevance and appeal – are then widely disseminated. The resources “go viral” in some form or another. The community that is now validating them and assigning them value is now much wider in scope and may exist in contexts that are quite distinct from that in which the resources initially emerged.

The effective use of a social media aggregator, such as a blog or a wiki or a more dedicated social media aggregator offered by a provider, would represent a shift in the participants’ mastery of a range of social media. This would indicate that they have a range of effective digital skills to use to curate digital content, as well as to negotiate with a number of third parties including groups, such as local history groups, as well as cultural and educational institutions.

(7) Accreditation: Collections of resources may be recognised as definitive, publishable, in need of protection, or other such formal recognition of their value (quality, distinctiveness, relevance). Individuals and communities may have their work on the resources recognised by the formal award of credit from an educational provider, or some other mark of status or achievement, perhaps an exhibition, further commissions, etc.

It must be stressed that this model is an ideal. In reality, later stages are often never reached, and some may be bypassed, or take place without the participation of effective learning champions, adequate levels of community participation, and so on.

Di Blas, N., Fiore, A., Mainetti, L., Vergallo, R., & Paolini, P. (2014). A portal of educational resources: providing evidence for matching pedagogy with technology. Research in Learning Technology, 22. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v22.22906

Learning object repositories can be difficult to navigate, and the educational material difficult to integrate into online courses. Schoonenboom, Sligte, and Kliphuis (2009) observe that the literature on the reuse of learning materials has largely focused on the development of materials. The authors developed guidelines that support staff and/or management in cases of (un)successful reuse of existing digital materials and provided methods for teachers in higher education in such cases.

The authors observe that the tendency of current repositories is to retain content in the form of a broad mix of text documents, videos, audio files and graphics (EDRENE 2009). It also emerges that a few repositories include non-digital materials (e.g. text books). A little less than a third of repositories surveyed have a mix between free and commercial material. What is relatively clear is that educational repositories are mainly created to share learning objects, often characterised by metadata or ready-made courses, intended as an organised set of learning resources related to a specific discipline. However, they largely fail to provide a whole, fully described and reproducible learning experience that can clarify when, where and how materials, digital or not, were used; how the learning process was organised; what educational goals were planned; which educational benefits were generated and what the role of the technology was.

It’s not an in-depth analysis, just a quick look at one particular journal. However, I’m pleased with what I came away with. If you’re reading this and know related stuff I should be aware of, please share in the comments below!