Voodoo categorisation and dynamic ontologies in the world of OER

Note: this appeared on the now-defunct MoodleNet blog in April 2019. It’s something to which I keep wanting to refer but always struggle to re-find — so I’m republishing it here. (Thanks, Creative Commons licensing!) The MoodleNet project to which it refers no longer exists in its original ambitious form, and some of the information it contains may be out of date. However, I’m still interested in the broad-brushstroke ideas.

Introduction

In a previous post on this blog, I described how we’re planning for search to work in MoodleNet. In this post, I want to dig into tagging and categorisation – which, it turns out, is an unexpectedly philosophical subject. Fundamentally, it comes down to whether you think that subjects such as ‘History’ and ‘Biology’ are real things that exist out there in the world, or whether you think that these are just labels that humans use to make sense of our experiences.

What follows is an attempt to explain why Open Educational Resources (OER) repositories are often under-used, how some forms of categorisation are essentially an attempt at witchcraft, and why assuming user intent can be problematic. Let’s start, however, with everyone’s favourite video streaming service.

Netflix

If you asked me what films and documentaries I like, I’d be able to use broad brushstrokes to paint you a picture. I know what I like and what I don’t like. Despite this, I’ve never intentionally sat down to watch ‘Critically-acclaimed Cerebral Independent Movies’ (Netflix code: 89), nor ‘Understated Social & Cultural Documentaries’ (Netflix code: 2428) nor even ‘Witty Independent Movies based on Books’ (Netflix code: 4913). These overlapping categories belong to a classification system developed by Netflix that now stretches into the tens of thousands of categories.

Netflix is popular because the content it provides is constantly updating, but mainly because it gets to know you over time. So instead of presenting the user with a list of 27,000 categories and asking them to choose, Netflix starts from a basis of the user picking three movies they like, and then making recommendations based on what they actually watch.

There aren’t a lot of actions that users can perform in the main Netflix interface: it’s essentially ‘browse’, ‘add to list’ and ‘play’. In addition, users don’t get to categorise what they watch. That categorisation is instead performed through a combination of Netflix’s algorithm and their employees, which work to create a personalised recommendation ‘layer’ on top of all of the content available.

In other words, Netflix’s categorisation is done to the user rather than by the user. Netflix may have thousands of categories and update them regularly, but the only way users can influence these is passively through consuming content, rather than actively – for example through tagging. More formally, we might say that Netflix is in complete control of the ontology of its ecosystem.

Voodoo categorisation

In a talk given back in 2005, media theorist Clay Shirky railed against what he called ‘voodoo categorisation’. This, he explained, is an attempt to create a model that perfectly describes the world. The ‘voodoo’ comes when you then try to act on that model and expect things to change that world.

Shirky explains that, when organisations try to force ‘voodoo categorisation’ (or any form of top-down ontology) onto large user bases, two significant problems occur:

- Signal loss – this happens when organisations assume that two things are the same (e.g. ‘Bolshevik revolution’ and ‘Russian revolution’) and therefore should be grouped together. After all, they don’t want users to miss out on potentially-relevant content. However, by grouping them together, they are over-estimating the signal loss in the expansion (i.e. by treating them as different) and under-estimating the signal loss in the collapse (i.e. by treating them as the same).

- Unstable categories – organisations assume that the categories within their ontology will persist over time. However, if we expand our timescale, every category is unstable. For example, ‘country’ might be seen as a useful category, but it’s been almost thirty years since we’ve recognised East Germany or Yugoslavia.

The ontologies we use to understand the world are coloured by our language, politics, and assumptions. For example, if we are creating a category of every country, do we include Palestine? What about Taiwan? These aren’t neutral choices and there is not necessarily a ‘correct’ answer now and for all time. As Shirky points out, it follows that someone tagging an item ‘to_read’ is no better in any objective way than conforming to a pre-defined categorisation scheme.

This is all well and good theoretically, but let’s bring things back down to earth and talk very practically about MoodleNet. How are we going to ensure that users can find things relevant to what they are teaching? Let’s have a look at OER repositories and the type of categories they use to organise content.

OER repositories

The Open Education Consortium points prospective users of OER to the website of the Community College Consortium for Open Educational Resources. They have a list of useful repositories, from which I’ve chosen three popular examples, highlighting their categories:

[the original post had a JavaScript-powered gallery that is now lost]

These repositories act a lot like libraries. There are a small number of pre-determined subject areas into which resources can be placed. In many ways, it’s as if there’s limited ‘shelf space’. What would Netflix do in this situation? After all, if they can come up with 27,000 categories for films and TV, how many more would there be for educational resources?

Ultimately, there are at least three problems with OER repositories organised by pre-determined subject areas:

- Users have to fit in with an imposed ontology

- Users have to know what they are looking for in advance

- Users aren’t provided with any context in which the resource may be used

We are trying to rectify these problems in MoodleNet, by tying together individual motivation with group value. Teachers look for resources which have been explicitly categorised as relevant to the curriculum they are teaching. Given the chance, great teachers also look for ideas in a wide range of places, some of which may be seen as coming from other disciplines. MoodleNet then allows them to provide the context in which they would use the resource when sharing their findings with the community.

Dynamic ontologies in MoodleNet

Our research has shown that, as you would expect, educators exhibit differences in the way they approach finding educational resources. While there are those that go straight to the appropriate category and browse from there, equally there are many who prefer a ‘search first and filter later’ approach. We want to accommodate the needs of both.

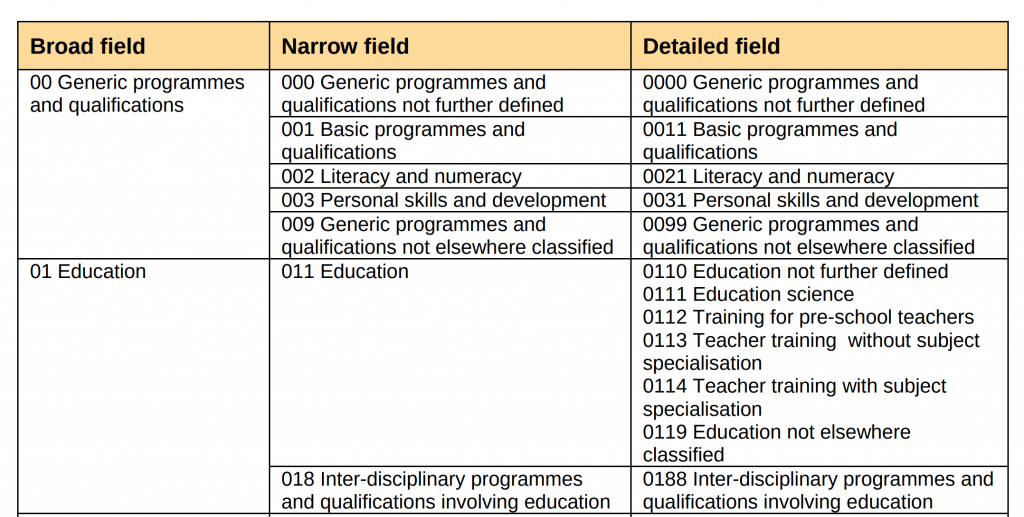

The solution we are proposing to use with MoodleNet includes both taxonomy and folksonomy. That is to say, it involves both top-down categorisation and bottom-up tagging. Instead of coming up with a bespoke taxonomy we are thinking of using UNESCO’s International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) fields of education and training which provides a three-level hierarchy, complete with relevant codes:

MoodleNet will require three types of taxonomic data to be added to communities, collections, and user profiles:

- Subject area (ISCED broad, narrow, or detailed)

- Grade level (broadly defined – e.g. ‘primary’ or ‘undergraduate’)

- Language(s)

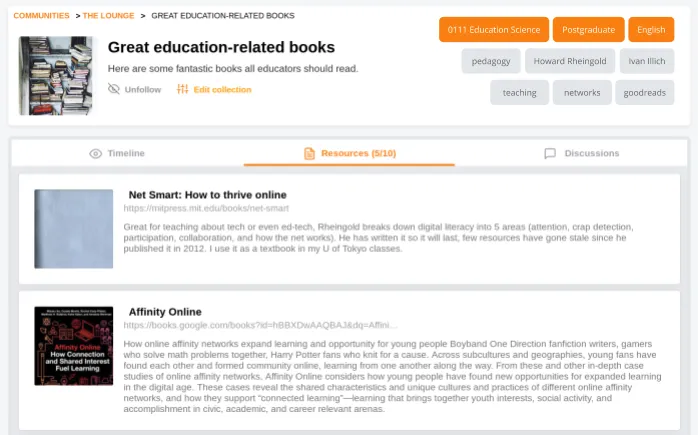

In addition, users may choose to add folksonomic data (i.e. free-text tagging) to further contextualise communities, collections, and profiles. That would mean a collection of resources might look something like this:

The way Clay Shirky explains this approach is that “the semantics are in the users, not in the system”. In other words, the system doesn’t have to understand that the Bolshevik Revolution is a subset of 20th century Russian history. It just needs to point out that people who often tag things with ‘Lenin’ also tag things with ‘Bolshevik’. It’s up to the teacher to make the professional judgement as to the value of a resource.

We envisage that this combination of taxonomic and folksonomic tagging will lead to a dynamic ontology in MoodleNet, powered by its users. It should allow a range of uses, by different types of educators, who have varying beliefs about the world.

Conclusion

What we’re describing here is not an easy problem to solve. The MoodleNet team does not profess to have fixed issues that have beset those organising educational for the past few decades. What we do recognise, however, is the power of the web and the value of context. As a result, MoodleNet should be useful to teachers who are looking to find resources directly relevant to the curriculum they are teaching. It should also be useful to those teachers looking to cast the net more widely

In closing, we are trying to keep MoodleNet as flexible as possible. Just as Moodle Core can be used in a wide variety of situations and pedagogical purposes, so we envisage MoodleNet to be used for equally diverse purposes.

Voodoo dolls image CC BY Siaron James