TB871: Going beyond WEIRD biases

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

As mentioned in a previous post, recent research in behavioural economics and evolutionary psychology has shed light on why humans often make seemingly irrational choices. Behavioural economics focuses on how people’s decisions deviate from classical economic theories of rationality, while evolutionary psychology examines how these choices may have been advantageous in our hunter-gatherer past. These fields suggest that our built-in biases, once beneficial for survival, now manifest as errors in modern contexts.

A seminal study entitled ‘The Weirdest People in the World?’, challenges our understanding of human thinking by revealing a significant bias in psychological research. This meta-study suggests that much of what we consider to be universally true about human cognition is based on findings from a narrow, unrepresentative segment of the global population. This segment, termed WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic), is disproportionately represented in psychological research.

The authors of the study state:

Behavioral scientists routinely publish broad claims about human psychology and behavior in the world’s top journals based on samples drawn entirely from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic (WEIRD) societies. Researchers—often implicitly—assume that either there is little variation across human populations, or that these “standard subjects” are as representative of the species as any other population. Are these assumptions justified? Here, our review of the comparative database from across the behavioral sciences suggests both that there is substantial variability in experimental results across populations and that WEIRD subjects are particularly unusual compared with the rest of the species—frequent outliers. The domains reviewed include visual perception, fairness, cooperation, spatial reasoning, categorization and inferential induction, moral reasoning, reasoning styles, self‐concepts and related motivations, and the heritability of IQ. The findings suggest that members of WEIRD societies, including young children, are among the least representative populations one could find for generalizing about humans. Many of these findings involve domains that are associated with fundamental aspects of psychology, motivation, and behavior—hence, there are no obvious a priori grounds for claiming that a particular behavioral phenomenon is universal based on sampling from a single subpopulation. Overall, these empirical patterns suggests that we need to be less cavalier in addressing questions of human nature on the basis of data drawn from this particularly thin, and rather unusual, slice of humanity.

(Henrich, Heine & Norenzayan, 2010, p.2)

The authors demonstrate that WEIRD subjects often show distinct psychological traits compared to non-WEIRD populations. For instance, in spatial cognition, WEIRD individuals typically exhibit an egocentric bias, while non-WEIRD groups often use allocentric reasoning. Similarly, differences are noted in social decision-making, moral reasoning, and self-concept. These findings highlight the importance of considering cultural contexts in psychological studies and caution against overgeneralising results from WEIRD populations.

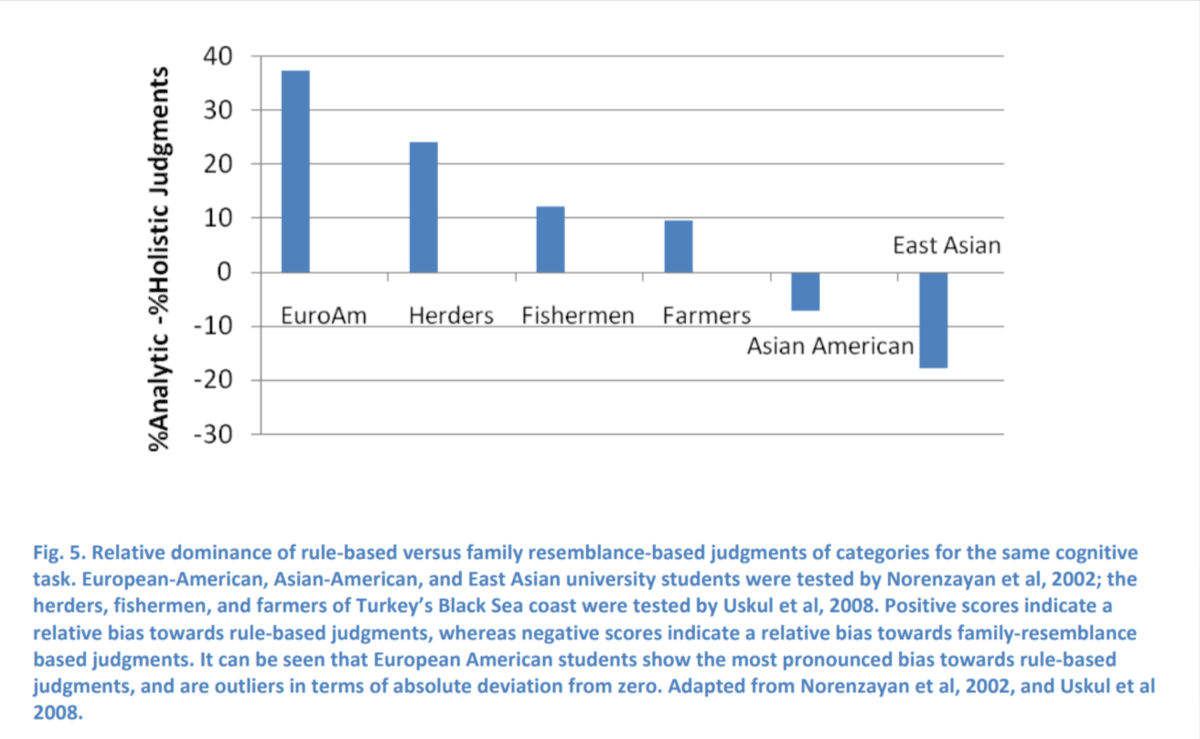

One key aspect explored in the study is the difference between analytic (rule-based) and holistic (family resemblance-based) thinking. The following diagram taken from the paper illustrates this contrast by showing the relative dominance of these cognitive styles across different cultural groups:

The diagram compares European-American, Asian-American, and East Asian university students, alongside herders, fishermen, and farmers from Turkey’s Black Sea coast. It highlights that European American students exhibit the most pronounced bias towards rule-based judgments, while other groups show varying degrees of holistic thinking. This evidence indicates that societies and cultures are not all equally predisposed to systems thinking, which requires the ability to think holistically and in process terms.

This insight is crucial for systems thinking, which relies on holistic and process-oriented thinking. The Henrich et al. study indicates that not all cultures are equally predisposed to this type of thinking. Therefore, when engaging with diverse cultures, we must remain mindful of these differences to encourage better understanding and collaboration.

Section 3.3 of the paper further delves into the implications of these differences in thinking styles for various cognitive domains, such as social interactions, problem-solving approaches, and educational practices. For example, the preference for analytic thinking in WEIRD societies often leads to a focus on categories and rules, while holistic thinkers from non-WEIRD societies might approach problems by considering relationships and contexts.

This difference can influence how people from different cultures collaborate and make decisions. In professional and educational settings, understanding these cognitive styles can improve communication and teamwork by recognising and valuing diverse perspectives. Moreover, appreciating these differences can lead to more effective strategies in fields like marketing, policy-making, and international relations, where cultural sensitivity is paramount.

By acknowledging and addressing these biases, we can develop a more accurate and comprehensive view of human behaviour, ultimately enhancing our ability to understand and connect with people from diverse cultural backgrounds.

References

- Henrich, J., Heine, S.J. and Norenzayan, A. (2010) ‘The weirdest people in the world?’ Rochester, NY. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1601785.