TB871: Russell Ackoff as a systems thinking pioneer

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

Russell Ackoff was a key figure in systems thinking who left an enduring impact through his innovative approaches and concepts. His work spanned various domains, from organisational theory to systems science, and he is well-known for his emphasis on holistic thinking and interactive planning. I mentioned his work in a previous post.

Ackoff didn’t like being called a ‘consultant’, preferring the term ‘educator’ as he believed consultants impose solutions, whereas educators help people discover their own solutions. This distinction is a good example of his underlying philosophy of empowering individuals to solve their own problems rather than providing predefined solutions (Ramage and Shipp, 2020, p. 141).

Ackoff embodied wholeness, seamlessly integrating complementary opposites. He combined forcefulness with kindness, illustrating the harmonious merging of seemingly contradictory qualities (Ibid., p. 142). He observed that society has moved from the machine age, which focused on analytical thinking, to the systems age, emphasising synthetic thinking and understanding wholes. He viewed all objects and experiences as parts of larger systems, reflecting a holistic perspective on the world (Ibid., pp. 143-144).

Complex situations as ‘messes’

Ackoff introduced the concept of a “mess” to describe complex systems of interacting problems. He argued against breaking down a mess into parts, as this approach can worsen the situation. Instead, he advocated for managing messes holistically, considering all interrelated aspects simultaneously (Ibid., p. 144).

What Ackoff termed ‘interactive planning’ involves designing a system that one would ideally want to replace the existing one with. He outlined five stages of interactive planning:

- Formulating the mess

- Ends planning (designing the desirable future)

- Means planning (finding ways to reach the desirable future)

- Resource planning (deciding what resources are required and how to obtain them)

- Design of implementation and control (putting changes into place and monitoring them)

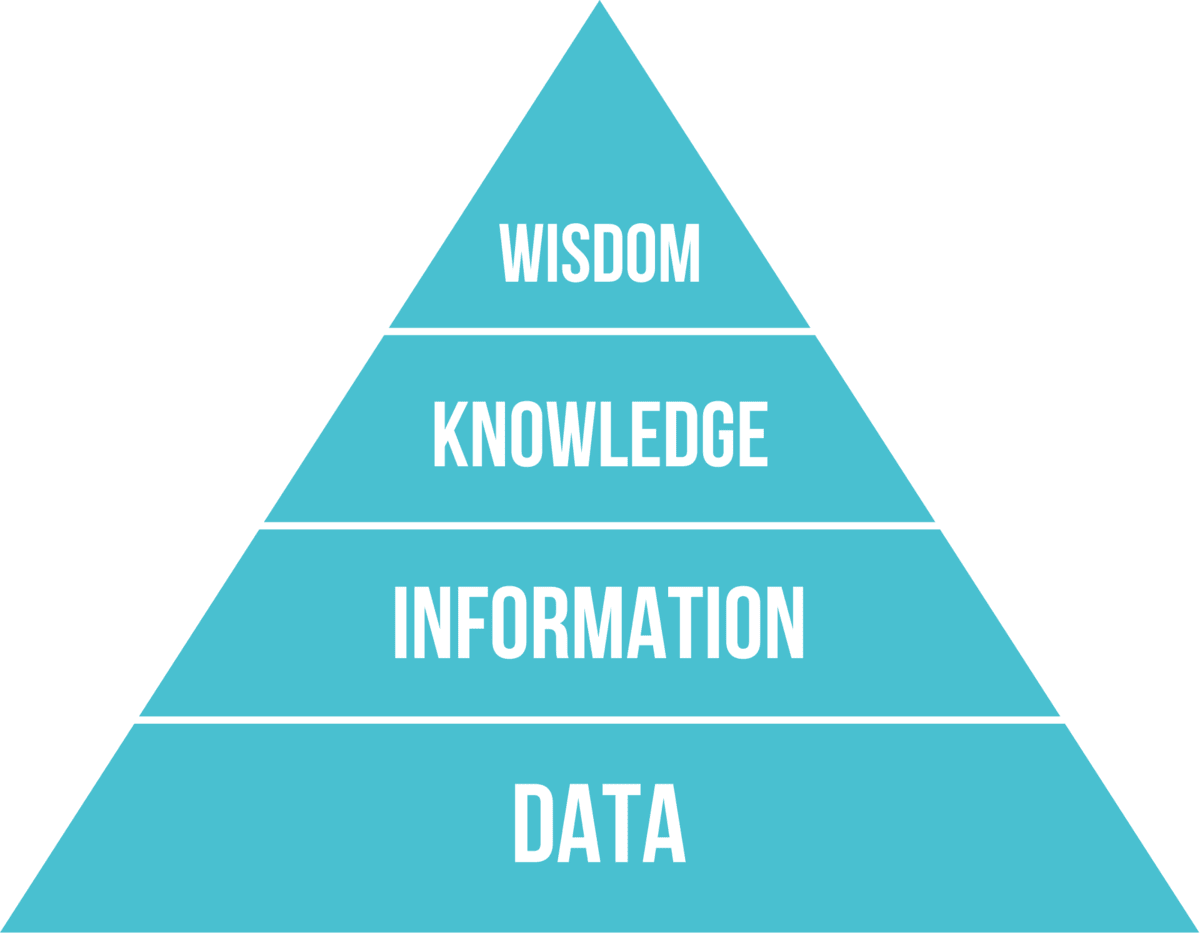

Ackoff also introduced the hierarchy of Data, Information, Knowledge, and Wisdom (DIKW), describing the progression from simple data to valuable wisdom. This hierarchy is widely used in knowledge management (Ibid., p. 144).

Ackoff’s concept of interactive planning was proactive, aiming not just to solve problems but to dissolve them by changing the environment that generates them. This forward-thinking approach aligns with his belief that organisations should aim for idealised designs, envisioning the best possible future and working towards it rather than merely reacting to issues as they arise.

Fun and philosophy

Ackoff’s philosophy on work and pleasure is encapsulated in his statement, “For me, there has never been an amount of money that makes it worth doing something that is not fun” (Ibid., p.145). I can definitely agree with that!

In his career, he identified five sources of fun:

- Denying the obvious and exploring its consequences: Ackoff found enjoyment in challenging widely accepted truths and exploring the outcomes. This approach not only sparked curiosity but also led to innovative thinking and solutions. For instance, he questioned the effectiveness of traditional educational methods, advocating for experiential learning over rote memorisation.

- Proving that large social Systems often pursue incorrect objectives: He demonstrated that large social systems frequently aim for the wrong goals. For instance, the educational system prioritises teaching over learning, which obstructs the latter. Similarly, corporations often focus on enhancing the quality of life for managers rather than maximising shareholder value (Ibid., pp.146-147). Ackoff argued that these misaligned objectives lead to inefficiencies and systemic failures.

- Producing conceptual order where there was ambiguity and confusion: Creating order from chaos was another source of fun for Ackoff. He achieved this by identifying the DIKW hierarchy, defining the three traditional types of management and proposing the interactive manager as a fourth type, and finding ways to control the future through methods such as vertical and horizontal integration, cooperation, incentives, and responsiveness (Ibid., pp.147-148). His ability to synthesise complex ideas into coherent frameworks helped organisations navigate uncertainty and make better decisions.

- Disclosing intellectual ‘con men’: Ackoff took pleasure in exposing the flaws of popular management trends like TQM, benchmarking, downsizing, process reengineering, and scenario planning. He criticised these trends for offering simplistic solutions to complex problems without considering systems thinking (Ibid., p.148). He argued that many of these approaches were fads, lacking the depth required to address real organisational issues effectively.

- Designing organisations that avoid common traps He enjoyed designing organisations that bypass common management pitfalls. His innovative designs included democratic hierarchies, internal market economies, multidimensional structures, and systems that support learning and adaptation (Ibid., pp.148-149). Ackoff’s organisational designs aimed to empower employees, encourage innovation, and create environments where continuous learning and improvement were integral to the corporate culture.

Russell Ackoff exemplified his principles of systems thinking through his actions, embodying the philosophies he advocated. He consistently applied holistic thinking and participatory methods in his work with organisations, ensuring that his theoretical concepts were grounded in practical application.

Ackoff’s approach to problem-solving was not just academic; he actively engaged with real-world issues and demonstrated the effectiveness of his ideas in practice. He famously said, “The only thing harder than starting something new is stopping something old,” highlighting his commitment to continuous improvement and innovation within systems (Ackoff, 1999, p. 426). This dedication to both theory and practice solidified his reputation as a practitioner who truly ‘walked the talk.’

References

- Ackoff, R. L., 1999. On Passing through 80. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 12(4), pp. 425-430.

- Ramage, M. and Shipp, K., 2020. Systems Thinkers. 2nd ed. Milton Keynes: The Open University/London: Springer.