TB871: Four Stages of Competence (and the Johari Window)

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

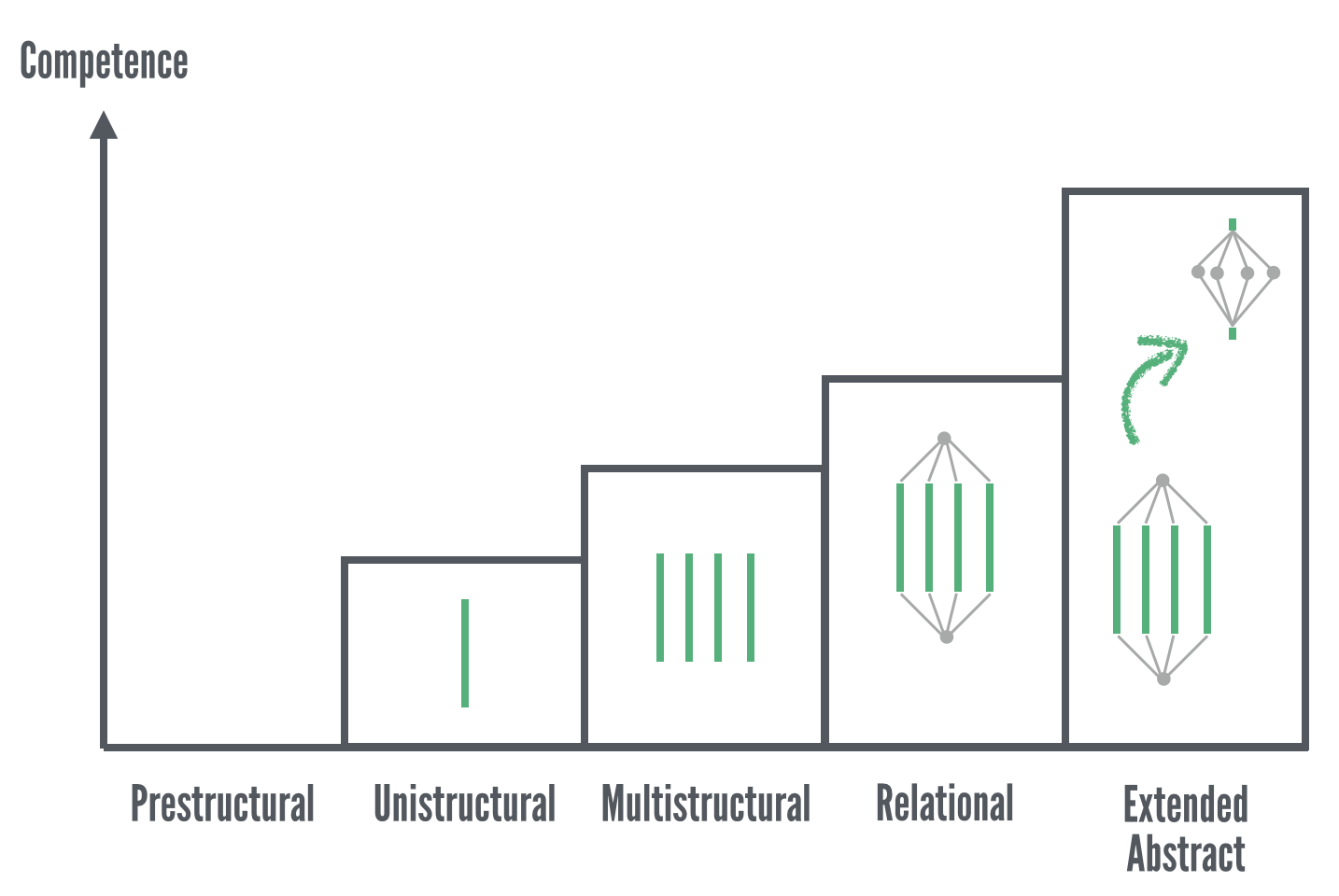

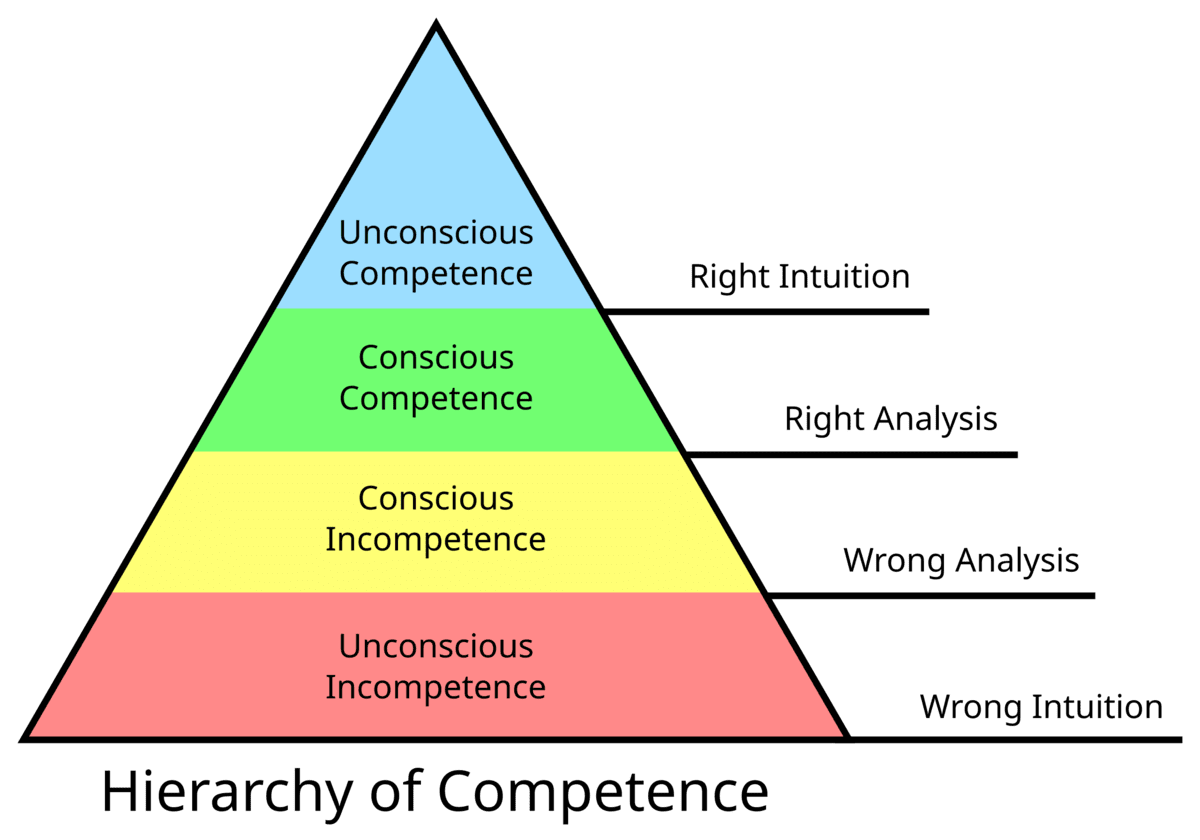

The Four Stages of Competence, also known as the Conscious Competence Learning Model, is a framework used in psychology and education to help individuals understand their journey from incompetence to mastery (‘Four Stages of Competence’, 2024).

The initial stage, Unconscious Incompetence, is where individuals are unaware of their lack of a particular skill. They do not recognise their deficits and may even deny the usefulness of the skill. For example, I’ve experienced rejections for jobs I’ve applied for without feedback .This can leave job seekers unaware of the specific skills needed for improvement.

At the Unconscious Incompetence stage, transparent feedback mechanisms and opportunities to observe skilled practitioners are important. Meanwihle constructive feedback, mentorship programmes, and self-assessment tools can provide the necessary support.

Moving to Conscious Incompetence, individuals become aware of their incompetence and recognise the value of acquiring the new skill. This stage is often marked by the realisation of mistakes as part of the learning process. For instance, I realised that I didn’t know much about Systems Thinking but it seemed relevant to my professional life. So I decided to Systems Thinking through an MSc programme giving me a structured way to learn the necessary knowledge and skills.

For Conscious Incompetence, this kind of structured learning programme and access to comprehensive resources can be ideal. Additionally, peer study groups, workshops, and extensive learning materials help individuals at this stage.

In the Conscious Competence stage, individuals start to acquire the skill and consciously apply it. This requires significant effort and concentration. For me, applying skills in project management and learning design with conscious effort and focus would be good examples.

As individuals reach Conscious Competence, they need opportunities for practical application and to receive continuous feedback. Collaborative projects, such as the ones WAO works on, performance reviews (if you work in that sort of organisation), and real-world practice scenarios are helpful.

Finally, Unconscious Competence is reached when the skill becomes second nature. Individuals can perform the skill effortlessly and may be able to teach it to others. For example, over the past weeks I’ve been recognised as a warm and generous facilitator for online events. I didn’t even think about this, which shows that I’m doing it effortlessly.

For those at the Unconscious Competence stage, mentorship roles, leadership opportunities, and continuous professional development are ideal conditions. Advanced training, leadership roles, and opportunities to mentor others support this stage.

It struck me, especially given that the module materials represented the four stages as four quadrants of a square (The Open University, 2020), that this has overlaps with another technique that I’ve used before.

Comparing and contrasting with the Johari Window

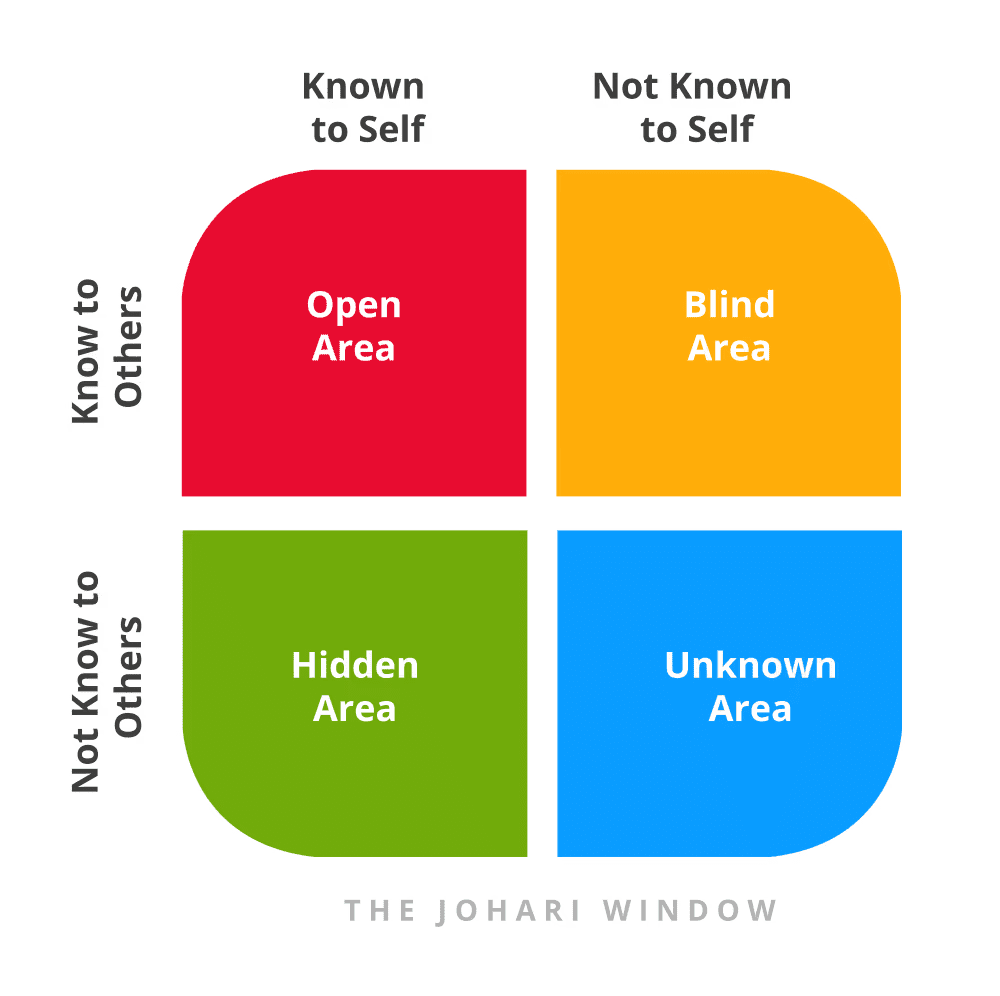

The Johari Window is a psychological tool used to improve self-awareness and mutual understanding. in other words, it’s a technique designed to help people better understand their relationship with themselves and others. Designed as a heuristic exercise by Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham, the ‘Johari’ window is named after a combination of their first names (‘Johari Window’, 2023)

This approach complements the Four Stages of Competence by focusing on self-disclosure and feedback.

| Aspect | Four Stages of Competence | Johari Window |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 Lack of awareness | Unconscious Incompetence Not aware of the lack of a skill or need to learn it. | Blind Area (Unknown to self, Known to others) Aspects of self that others see but you do not. |

| Stage 2 Awareness of the need to improve | Conscious Incompetence Aware of the lack of skill and need to learn it. | Open Area (Known to self and others) Aspects of self that are known and shared. |

| Stage 3 Effort to improve is known internally but may not be visible to others | Conscious Competence Learning and practising the skill with conscious effort. | Hidden Area (Known to self, Unknown to others) Aspects of self that you know but others do not. |

| Stage 4 Skill becomes second nature; internal processes are automatic and not always visible (or understood) | Unconscious Competence Mastery of the skill, performed without conscious thought. | Unknown Area (Unknown to self and others) Aspects of self that neither you nor others are aware of. |

It’s not a perfect fit between the Four Stages of Competence model and the Johari Window, but there’s enough of an overlap for me to mentally file it in a similar place.

Application to Systems Thinking

Applying the Four Stages of Competence to systems thinking highlights the progression individuals undergo in mastering this complex discipline. Initially, one might not recognise the need for systems thinking skills, but through structured learning and feedback, awareness grows, marking the shift to conscious incompetence. As students engage with concepts and tools, such as those offered in my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice, they enter conscious competence, where deliberate practice and application in real-world scenarios become essential.

Ultimately, with extensive experience and reflection, systems thinking becomes second nature, allowing practitioners to seamlessly integrate these skills into their professional and personal contexts. This journey highlights the importance of tailored support at each stage, ensuring that systems thinking principles are internalised and effectively used to address complex problems.

References

- ‘Four stages of competence’ (2024) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Four_stages_of_competence&oldid=1218241260 (Accessed: 26 July 2024).

- ‘Johari window’ (2023) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Johari_window&oldid=1179921061 (Accessed: 26 July 2024).

- The Open University (2020) ‘P4.3.1 Levels of competence’, TB871 Block 4 People stream [Online]. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2261494§ion=4.1 (Accessed 26 July 2024).