A couple of weeks ago, prompted by a post I wrote about Open Badges and HR, Alan Levine wrote a post entitled Seeking Evidence of Badge Evidence. He made many good points in it, which led to Nate Otto (Director of the Badge Alliance) to invite Alan, myself, and a couple of others to engage in a panel session during today’s Open Badges community call.

This post is me thinking out loud about Nate’s proposed questions:

- What type of evidence are people collecting for badges today?

- What are challenges and barriers to effectively using evidence with badges?

- What services and capabilities could be solutions to these challenges?

- Who should hold and control badge evidence? Issuers? Earners?

I’m going to answer these in two sections rather than point by point.

Problems with badge evidence

The claim I/we often make about Open Badges is that, unlike LinkedIn profiles or CV’s, they’re a bunch of evidence rather than a bunch of claims. I think we mean a couple of things by that.

First, we mean that we’ve got something to show for the experience we claimed to have had. In other words, even if the badge issuer doesn’t use the (optional) ‘evidence’ metadata field, there is still some kind of social proof to back up our claims.

The second thing we mean by badges being a bunch of evidence rather than being a bunch of claims is pointing to those that do in fact use the ‘evidence’ metadata field. At this point these seem few and far between. I think this is because:

- Organisations are still largely using badges in a ‘command and control’ top-down kind of way. In other words, creating one badge that is issued to many different individuals. This makes adding evidence onerous.

- Badges are being issued for relatively low-level things such as participation in workshops and conferences, rather than credentialing more high-stakes knowledge/skills/behaviours.

- People are misusing the criteria field as they are inexperienced (as we are all are, initially) in badge system design.

- There’s a lack of understanding about the best ways to deal with the evidence that sits behind badges. Whether due to privacy concerns, fears around cost or compliance, or institutional policies, adding evidence is seen as a burden rather than a gamechanger.

Some suggestions

Most of the clients I deal with have some sort of background in education, and many have experience in designing assessment systems. However, because Open Badges are open, distributed, and put the learner in control, they need assistance in how to think differently.

Here are some suggestions that I’ve made several times to organisations large and small:

1. Provide appropriate levels of credibility

As I’ve learned during my long-term consultancy with City & Guilds, credibility comes through the triangulation of validity, reliability, and viability. If you’re issuing a PhD-level badge, for example, the amount of ‘social proof’ required will be an order of magnitude greater than those badges issued for participation in an event.

2. Put learners/users at the centre of your system

One of the greatest barriers in terms of pushback issuers are likely to get from users of their badging system is privacy. Granular permissions around the evidence that sits behind a badge are important, especially if that evidence happens to be visual in nature (e.g. photos/videos).

There are ways around this using existing systems such as YouTube, Google Docs, and Flickr, but perhaps an extension to the Open Badges specification could provide a standard on which badge issuers could build?

3. Ask employers what they want

Open Badges aren’t only for helping people into a job, on the job, and onto the next job, but this is a common use case. Given this, if you’re a badge issuer, it’s probably worth thinking through in detail who is likely to be the viewer/consumer of your badges. Talking to them about what they would consider sufficient evidence is likely to be an interesting and enlightening conversation.

Conclusion

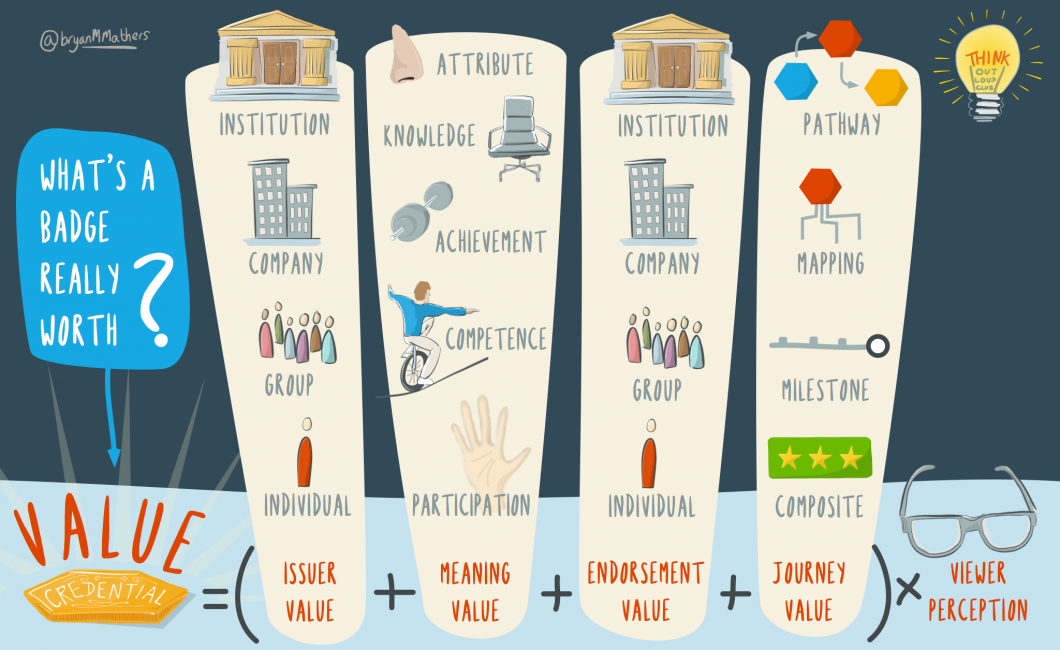

Being able to provide trusted evidence is a gamechanger when it comes to credentialing. One of the main reasons that Alan found it difficult to find ‘evidence of evidence’ is that we’re still using the same old metaphors and structures for issuing credentials.

As I argued in my Open Badges in Higher Education keynote and afterwards in the Q&A part of Serge Ravet‘s session, if we find more useful metaphors for people that ‘certificates’ then we’re likely to see different kinds of credentials — and hopefully with many more pointing to evidence than we have now!

Image CC BY-ND Bryan Mathers