The Silent Writing Collective is all about the process of writing, not about the word count or subsequently publishing it elsewhere. Still, I wrote almost 2,000 words in an hour and felt what I produced was decent enough to post here (unedited, but with formatting improvements).

Ever since the revelations about the National Security Agency in the US hit a few months ago, I’ve been meaning to write about them. Ostensibly, I should be in a position to give some guidance. I usually know enough, conceptually speaking, about privacy and security to be able to give advice to others.

This time, however, things are different. There’s nothing much you can really do when a large, powerful country like the USA decide to wield its power in an undemocratic way. Not only have they got access to a bewildering array of technological innovations, but they’re doing so in a secret way. Just check out the statement on Lavabit’s front page:

I have been forced to make a difficult decision: to become complicit in crimes against the American people or walk away from nearly ten years of hard work by shutting down Lavabit. After significant soul searching, I have decided to suspend operations. I wish that I could legally share with you the events that led to my decision. I cannot. I feel you deserve to know what’s going on–the first amendment is supposed to guarantee me the freedom to speak out in situations like this. Unfortunately, Congress has passed laws that say otherwise. As things currently stand, I cannot share my experiences over the last six weeks, even though I have twice made the appropriate requests.

Lavabit was the encrypted email service used by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden. Reading between the lines, it appears that the NSA wanted Lavabit to give them access to at least his email account, if not unfettered access to *everyone’s* account. This mixture of absolute power and secrecy is extremely worrying. Not only does it mean they are beyond the control of ‘the people’ in any jurisdiction, but I’m left wondering what kind of advice it’s even worth giving out.

I try to walk the walk in my technological life. I don’t recommend people use things that I don’t use myself. While others I’ve seen on Twitter, Hacker News and other online spaces have attempted to lock things down, I’ve felt a bit powerless. On the one hand, I too want to lock things down. While there’s no clear and present data of me being locked up for anything, I’m not a big fan of some bored NSA employee being able to find out more about me than even I know about myself.

Absolute power corrupts absolutely. We know that. But the response to the revelations amongst the general public so far seems to be ‘meh’. Some have used the classic response of ‘if you’re doing nothing wrong you’ve got nothing to fear’. This is so wrong-headed it’s unbelievable. We all break laws every day – even though the laws of the UK are finally online. If someone has access and can dig through everything you do then of course they’ll find something incriminating. It’s so close to an Orwellian nightmare it’s untrue.

I already overshare on the Internet, it’s true. But that’s both a tactic and an expression of who I am. I believe in my right to free and openly express who I am – and more importantly, how I want to be seen – to the world at large. The thing that concerns me is that I don’t really know where the NSA’s knowledge of me and my actions starts and stops. Apparently they have the ability to eavesdrop on conversations by firing a laser beam at a plastic cup in the same room as their target. Or even a window. There’s a reason why we put curtains on our windows. The spaces in which we know we’re alone (or alone with significant others) are important for self-development and, dare I say it human flourishing.

So what have I done in response to the NSA revelations? Not much, really. I’ve talked a good game and explored various options. I’ve kept up with the news and various articles linked to from Hacker News and The Guardian. But I haven’t actually done much. Part of that is because I don’t want to take the hit on my productivity – many of the ‘more secure’ replacements aren’t as slick or frictionless – but partly for another reason: I don’t feel like my weaponry against governments should be extreme crypto. I feel that it should be democratic processes. If someone or some organisation is abusing it’s power, then the people should have some recourse against them. Even if it’s a different sovereign country, the people of my country should be able to put pressure on them to do something about it.

Some of the things I’ve considered doing include switching from running Mac OS X on my (or rather, Mozilla’s) MacBook Pro to a variant of Linux. The MacBook the machine I use most of the time. Only rarely – like now, actually, as I’m writing this – will I use a ThinkPad X61 running Chromium OS. I’ve tried to use Linux as my main operating system since 1997 when, as a 16 year-old, I bought a book on Red Hat Linux to try and get my head around it. I kind of know my way around some of the commands, but it greatly frustrates me when updates break really important things such as wireless networking. Macs just work in a way I hadn’t experienced before using them. I suppose this ‘Chromiumbook’ isn’t bad, but I just feel that everything I write is fuelling Google’s ad dollars.

I think there’s nothing much we can do from a technological point of view as individual users versus the might of the NSA. Indeed, it might make matters worse as apparently their default filter for ‘is this person dangerous?’ is ‘if they use encryption, yes’. That, of course, makes them not even worth parodying, but does make me want to throw my hands in the air. Instead, though, what I think it’s important to do is to think about security and privacy more generally. What is it that we want to be secure? Who do we want to protect our privacy from?

I’m only speaking for myself here, but I think it might be more widely applicable:

- I don’t want to be the victim of identity theft.

- I want to be able to surf the Web anonymously if what I’m looking at/for could potentially compromise me personally or professionally.

- While I’ve pretty much given up on email ever being secure, I want other communications to be locked down and visible to others only if at least one of the parties involved wants this to be the case.

- I want to be able to craft multiple, discrete pseudo-anonymous personas without being forced to reveal the connections between them.

I suppose, overall, I don’t want to be watched or feel that I’m being watched. This might seem odd coming from someone who seemingly tweets and otherwise shares a fair bit of detail from my life. The difference is that it’s under my control. You’re seeing glimpses into my life through the filter or lens that I choose to put on it. That’s autonomy. That’s freedom.

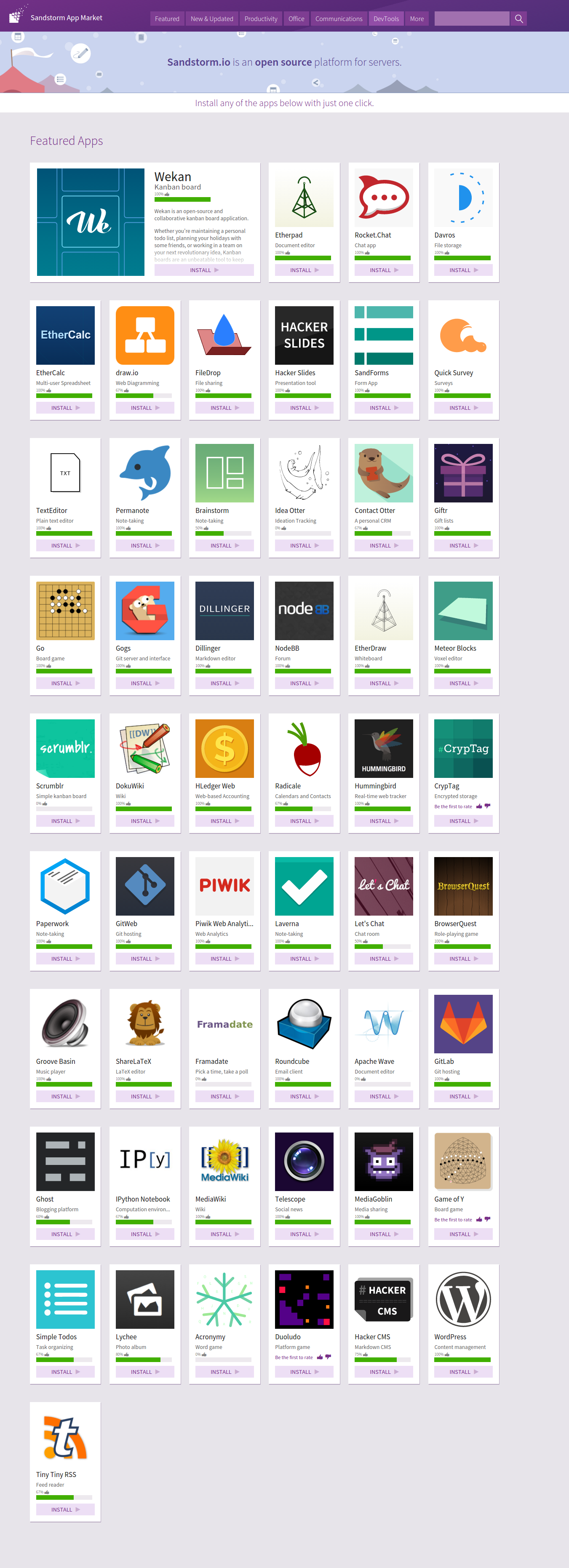

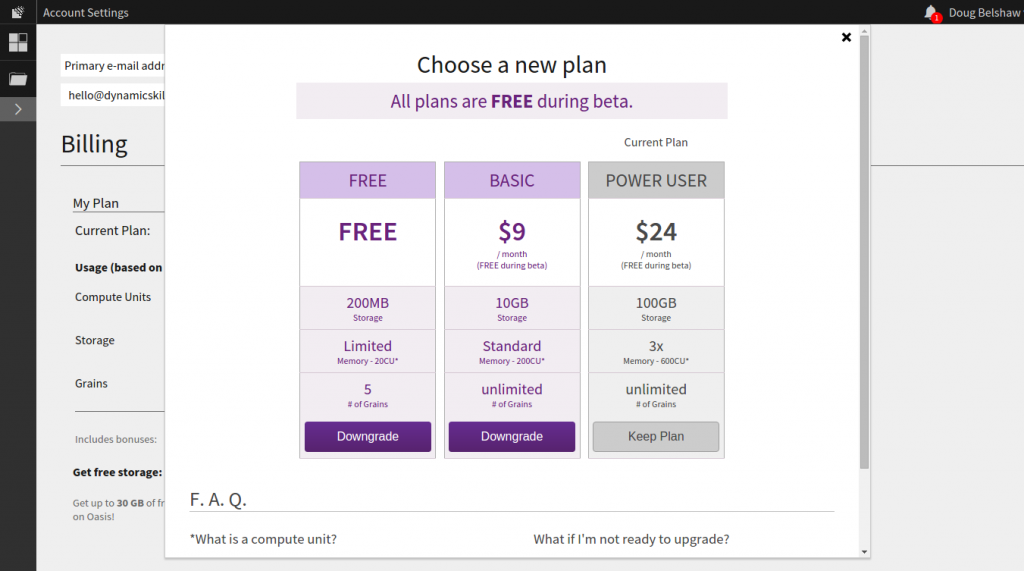

So I am going to make some changes, but I’m not going to go nuts. I’ll keep doing what I can to put pressure on the UK and US governments to do something about the NSA over-reaching. I’ll keep up to date and support organisations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation who campaign on our behalf (their Who’s Got Your Back 2013 is well worth a read). I’m going to see what’s available in terms of other services that may offer more privacy and security. But, instead of automatically jumping ship, I’ll attempt to weigh the productivity cost. If it doesn’t seem to be worth it, then I won’t do it.

For all I’ve written above about how important I see security and privacy, I’ve come to expect that the technological tools I use afford me a certain level of fluency and productivity. My job and professional reputation indirectly (and at times, directly) depend upon this. I suppose there’s a heavily performative notion in there: I have to not only be productive but be seen to be productive (at least in the construct that’s in my head).

Also, it’s important to have at least a connection to ‘the (wo)man on the street’. As soon as you look like, or come across as, a special case then people stop paying attention to you. I’ve experienced some of that because I wrote my doctoral thesis on digital literacies and/or because I now work for Mozilla. “It’s easy for you to say,” people exclaim. Well, it’s not actually. It’s difficult and tortuous and philosophically problematic. I spend far too long thinking about this kind of stuff.

What I think is important is that we build a bridge between those who think the NSA revelations show that western governments somehow have “got our back” and those who, in the words of Marc Scott, have glued a tinfoil hat to their heads. It’s important not to talk past one another on issues like these. After all, these aren’t issues around cryptography or terrorism but around freedom, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, writ large.

The thing that concerns me to the point of lying awake thinking at night is the world that my six year-old son and two year-old daughter will inhabit. My formative years were spent growing up with the Web in its Wild West, frontier town-feel years. Being able to put up a website (in my case, as a sixteen year old, one about Monty Python) and have it accessible anywhere in the world was mind-blowing. But it wasn’t just that. It was the fact that people could connect with one another without boundaries relating to power, geography, class or skin colour.

That’s the Web we’ve lost – it’s well worth reading Anil Dash for more on that. The networked world that my children will inhabit (unless we do something about it) will constrain instead of liberate. It will be something to fear instead of something to embrace. And that greatly saddens me.

So beyond making relevant changes to my own personal setup I suppose I’ve got a responsibility to educate those around me. First, I need to scare them into taking privacy and security seriously. But then, second, I need to show them what appropriate steps look like to protect that. And if, as in the case of the NSA, appropriate steps on a personal level aren’t enough, then I need to encourage them to take appropriate (collective) political action.

I hope this goes some way to explaining why I haven’t got a 10 step guide on what to do to change your hardware/software setup to be NSA-proof. You can’t be. But you, we together can agitate for a better world. That’s not to say we should be complacent about our technological setups. Not at all. Now, more than ever, is a great time to review the information and details that may be unintentionally leaking out to the wider world without your knowledge.

In conclusion, then, I’ll not be breaking out my tinfoil hat anytime soon. And I’ll not be locking down my machines to a ridiculous extent. I’ll be trying out new operating systems, software and even hardware, but still want to be able to use someone else’s machine without huge amounts of hassle. And I need, especially for work reasons, to be able to communicate with others without being some kind of ‘special case’ that other people have to tolerate or, more likely, avoid.

Image CC BY-NC-SA Truthout.org