This post comes from my (ongoing) Ed.D. thesis, which can be read in full over at http://dougbelshaw.com/thesis. You may want to check out my wiki to follow up references.

CC BY-SA luc legay

Some would reject the idea of a dialectic when it comes to literacy. Instead of encouraging an interplay of old and new conceptions of literacy, they would espouse a clear demarcation. New technologies call for new literacies – and perhaps, epistemologies:

[A] seemingly increasing proportion of what people do and seek within practices mediated by new technologies – particularly computing and communications technologies – has nothing directly to do with true and established rules, procedures and standards for knowing. (Lankshear & Knobel, 2006:242-3)

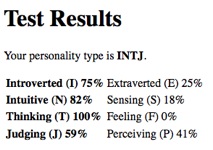

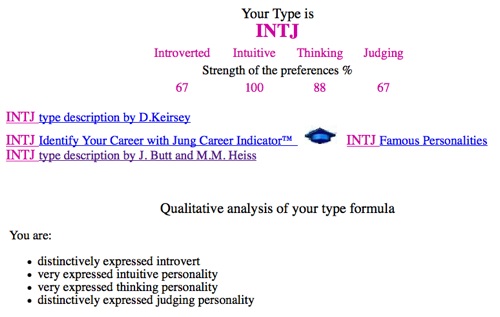

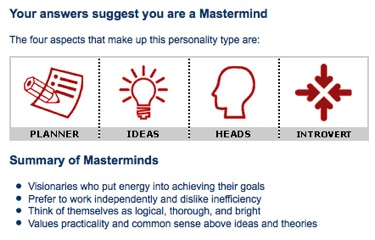

There are three main reasons why “what people do and seek within practices mediated by new technologies… [have] nothing to do with true and established… standards for knowing.” The first relates to the personality traits of people involved. A common internet saying is that “the geeks will inherit the earth” – certainly they are the early adopters, the first to figure out ways of using new technologies. By the time technologies reach the mainstream they are far from neutral having been tried, tested, accepted, rejected or accommodated by a ‘digital elite’. Skewed epistemologies can lead to skewed literacies.

The second reason why practices surround technology-mediated practices are different is down to identity. Digital interaction removes a layer of physicality from interactions. This can be liberating in the case of, for example, a burns victim or someone otherwise disabled or disfigured. It can also be ‘dangerous’ as individuals are often able to remain anonymous in online interactions. Physical interactions are bounded by time and space in a way that digital interactions are not. Whilst asynchronous interactions have been possible since the first marks were made in an effort to communicate, digital interactions go beyond what is possible with the book. In the latter, it is difficult to accidentally take something out of context as one has to deal with the book in its entirety. With digital interactions, however, it is much easier to misrepresent and distort the truth, even accidentally. Interactions and texts tend to be shorter online. Thus, in the fight for the soundbite distortion can take place.

Third, practices mediated by technology are different because of the element of community involved. Traditional Literacy, is predicated upon a scarcity model of education and exclusionist principles. An example of the latter is a near-synonym of ‘literate’ as ‘cultured’ (in the sense of having a knowledge of ‘high’ culture). Communities on this model are based on the who rather than the what – identity rather than interest. With technology-mediated practices, even ‘niche’ interests can be catered for.

These, then, are three reasons new technologies can be linked to new epistemologies. Whether new epistemologies necessarily lead to new literacies is an interesting question. As Erstad notes in quoting Wertsch (1998:43), all interaction is mediated and involves social and psychological processes. This is transformed when technology is used to do the communicating:

Regardless of the particular case or the genetic domain involved, the general point is that the introduction of a new mediational means creates a kind of imbalance in the systemic organization of mediated action, an imbalance that sets off changes in other elements such as the agent and changes in mediated action in general. (quoted in Erstad, 2008:180-1)

It is at this point that Lankshear and Knobel’s demarcation between ‘conceptual’ and ‘standardized operational’ definitions of literacy becomes useful. Conceptual definitions are what primarily interest us here – the extension of literacy’s “semantic reach” as opposed to ‘operationalizing’ what is involved in digital literacy and “advanc[ing] these as a standard for general adoption” (Lankshear & Knobel, 2008:2,3).

Instead of coining terms and giving existing concepts a ‘digital twist’, those who reject the dialectical approach propose ‘New Literacies’. They would reject Gilster’s (1997:230) assertion that ‘digital literacy is the logical extension of literacy itself, just as hypertext is an extension of the traditional reading experience.’ Instead, New Literacies theorists such as Lankshear and Knobel believe that ‘the more a literacy practice privileges participation over publishing, collective intelligence over individual possessive intelligence, collaboration over individuated authorship…, the more we should regard it as a ‘new’ literacy” (Lankshear & Knobel, 2006:60).

In an attempt to flesh out this conception of New Literacies, however, the authors tie themselves up in knots, so to speak. By seeking to explain what is ‘new’ about New Literacies, Lankshear and Knobel make reference to ‘a certain kind of technical stuff – digitality’ (2006:93) which seems to somewhat beg the question. What is ‘digitality’? They do concede, however, that ‘having new technical stuff is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for being a new literacy. It might amount to a digitized way of doing ‘the same old same old’.’ The authors attempt to deal with the difficulty of New Literacies involving identity by demarcating between ‘Literacy’ and ‘literacy’. Their demarcation is worth quoting in full (my emphasis):

Literacy, with a ‘big L’ refers to making meaning in ways that are tied directly to life and to being in the world (c.f. Freire 1972, Street 1984). That is, whenever we use language, we are making some sort of significant or socially recognizable ‘move’ that is inextricably tied to someone bringing into being or realizing some element or aspect of their world. This means that literacy, with a ‘small l’, describes the actual process of reading, writing, viewing, listening, manipulating images and sound, etc., making connections between different ideas, and using words and symbols that are part of these larger, more embodied Literacy practices. In short, this distinction explicitly recognizes that L/literacy is always about reading and writing something, and that this something is always part of a large pattern of being in the world (Gee, et al. 1996). And, because there are multiple ways of being in the world, then we can say that there are multiple L/literacies. (Lankshear & Knobel, 2006:233)

Earlier, Lankshear and Knobel moved from new technologies to new epistemologies, here they move from ontology to literacy. It is not clear, however, that such a move can be sustained. What do the authors mean by stating that ‘there are multiple ways of being in the world’? What constitutes a difference in these ways of being? Does each ‘way of being’ map onto a ‘literacy’? The authors claim that to be ‘ontologically new’ means to ‘consist of a different kind of ‘stuff’ from conventional literacies’ reflective of ‘larger changes in technology, institutions, media and the economy… and so on’ (Lankshear & Knobel, 2006:23-4).

This is so vague as to be effectively meaningless.