TB872: Avoiding systemic failures

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

When it comes to managing change effectively, the goal is to do it in a way that prevents the kind of problems that affect the whole system. These kind of problems are called systemic failures, and often bring unexpected negative results that can ripple through the entire structure we’re dealing with — whether it’s a business, a healthcare system, or a community.

The ‘sweet spot’ we’re aiming for is to make changes in a way that fits well with what everyone wants and what actually works in the real world. In other words, changes that are not only good in theory but also work well in practice (and are accepted by the culture of the organisation).

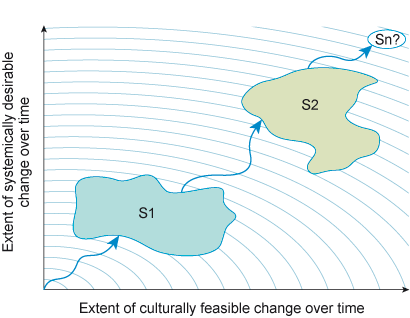

For example, with reference to the above diagram from the course materials, let’s say we’re looking at a situation where we want to make some changes (Situation 1 or ‘S1’). We’ve got an idea of where we want to get to (Situation 2 or ‘S2’). We might even have a vision for the future beyond that (referred to as ‘Sn’). The trick here is therefore figuring out what changes will be both systemically desirable (good for the system as a whole) and culturally feasible (acceptable/practical within the cultural context).

The diagram is like a map showing the journey of change which is a bit like watching ripples spread out after throwing a stone into a pond. The ripples represent the waves of change. The horizontal axis shows the extent of culturally feasible change over time, which we can understand as what changes the culture will accept, and when. Meanwhile, the vertical axis shows the extent of systemically desirable change over time, which we can understand as the changes that would be good for the system.

This is really interesting to me, as there are definitely some places that I’ve worked that were very resistant to change even when there was a general understanding it would be good for the whole system. Likewise, there have been others where they have adopted change much more readily.

Usually, though, getting the organisational culture to accept change takes longer than the amount of change that’s desirable. I usually sum this up by saying that humans are more difficult to deal with than technology! This discrepancy between desirable change and culturally-feasible change creates a pattern in the ripples (aka the journey of change).

When we’re trying to ‘manage’ change, therefore, it’s a constant balancing act between what’s best for the system with what the culture will support. This makes a lot of sense based on my career history. It’s basically an ongoing process of enquiry and understanding, specific to the context we’re in. It’s definitely true that what works in one place might not work in another, even if the context superficially looks similar.

The last thing to say is that what’s considered systemically desirable and culturally feasible now may change in the future. I guess that’s a bit like the Overton Window, but from system change perspective. Our job, of course, is to navigate this changing landscape carefully and thoughtfully.