How to teach using mobile devices

I’m mentioned in The Guardian today in a short article entitled How to teach using mobile phones. However, as is the case with such things, what appears and what I submitted are two different things. For a start, my emphasis was on mobile devices more generally (not just phones!)

Thankfully, they’ve still linked to the resources I was asked to produce. If the link in the article doesn’t work (it didn’t for me) just search ‘mobile devices’ at the Guardian Teacher Network. I’ve decided to reproduce what I originally wrote here:

If there’s one thing that’s guaranteed to be in the pocket or bag of every young person it’s some kind of mobile device. They may forget their planner or even a pen, but they’re unlikely to be without their mobile phone. This, understandably, can lead to some frustration.

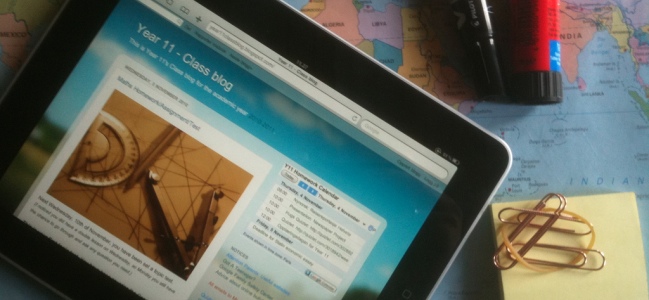

From the smartphone to the iPad to the Nintendo 3Ds the range of devices that young people have access to is growing – and so is their power to connect people. However, many parents, teachers and even children themselves are unsure as to how mobile devices can be used for anything more than entertainment. Do mobile devices have a place in the classroom? Are they merely distractions to learning?

On the Guardian Teacher Network, you can find now find a PowerPoint to get adults and children alike thinking about how they can use everything from their mobile phone to their games consoles for learning. The PowerPoint gives 10 different scenarios in which mobile devices could be used to add value to what goes on in the classroom – or even fundamentally change the types of activities that are available.

The associated Cribsheet gives suggestions and links to further resources as to how discussions about mobile devices can be framed with school governors, senior leaders, teachers, parents and children. There are many ways in which the resources can be used – everything from a PSHE lesson (perhaps drawing up guidelines to responsible and appropriate use) to Staff CPD or even a ‘town hall’ style meeting with parents.

With schools increasingly having the freedom and powers to innovate around the traditional curriculum through Academy, Trust or Free School status, now is a good time to be talking through the issues involved in mobile learning. Not only will it really engage pupils, but there’s the potential for it to be used as a ‘trojan horse’ for real curriculum change!

This was the second, more objective, draft. I’ve been promised that my first, longer and more polemicised draft will be used in a few weeks’ time. We’ll see.

PS Congratulations to @colport and the people behind #ukedchat – they’re mentioned in The Guardian today as well: Twittering classes for teachers

Image CC BY mortsan

Enough is enough. I think it was

Enough is enough. I think it was