cc-nc-nd by *wb-skinner

You cannot step twice into the same river. (Heraclitus)

The above quotation was on the wall of my classroom at my previous school. Heraclitus is also attributed as saying, “The road up and the road down is one and the same” (also on my wall). Heraclitus recognised that whilst there is nothing fundamentally new under the sun, nevertheless the whole universe is in a constant state of flux with nothing fixed. Heraclitus believed the secrets of the unvierse could be found in finding patterns in the changes that take place.

David Bohm was a quantum physicist who, in the 20th century, developed a theory that ‘invites us to understand the universe as a flowing and unbroken wholeness.’ (Morgan, 1998:214) A useful metaphor that Morgan uses pace Bohm is that of the whirlpool in a river. Whilst such a whirlpool has a relatively constant form, it does not exist separately from the movement of the river.

Four ‘logics of change’

Morgan addresses four ‘logics of change’ in his chapter Unfolding Logics of Change, namely:

- Autopoiesis

- Chaos & complexity

- Mutual causality

- Dialectical change

1. Autopoiesis

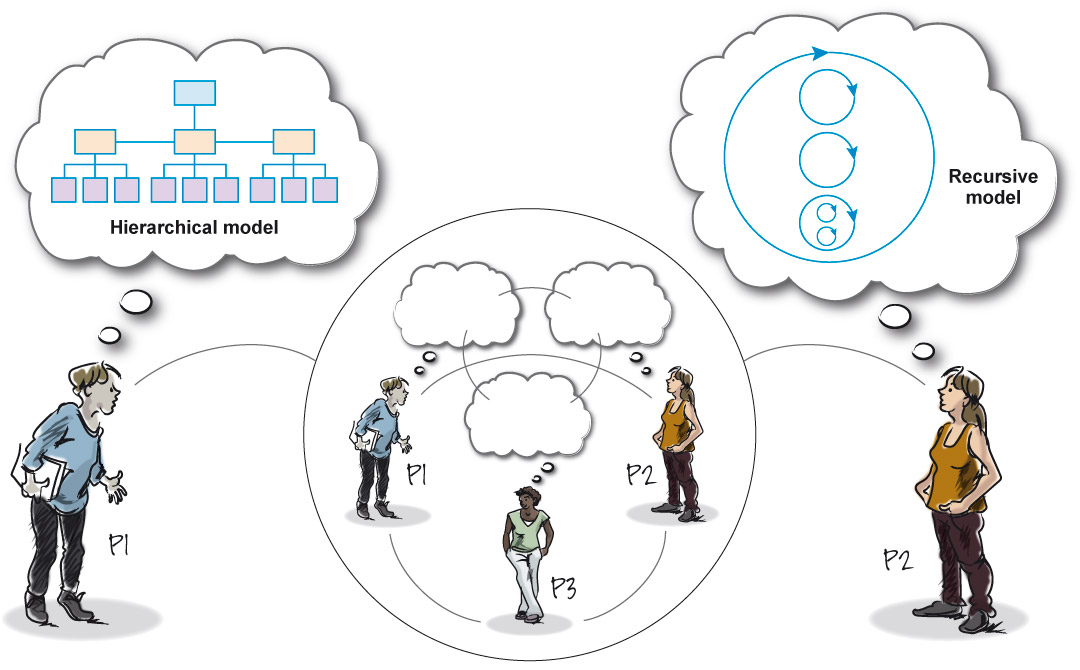

Traditional organization theories frame organizations in reference to their external environment. A new approach to systems theory was developed by Maturana and Varela which they termed Autopoiesis (from the Greek auto – for self- and poiesis for creation or production, literally ‘auto self production’). They argue that all living systems are ‘organizationally closed’ and make reference only to themselves. The idea, therefore, that such a system is open to an environment is the product of an external observer trying to make sense of it.

Maturana and Varela believe living systems to be characterized by autonomy, circularity and self-reference. These three features allow the system to self-create or self-renew. The aim of autopoietic systems is to produce themselves and therefore their own organization and identity is paramount.

In order to back up their theory, Maturana and Varela point to the brain as a ‘living system’. The brain, they contend, is ‘closed, autonomous, circular and self-referential.’ (Morgan, 1998:216) Although it seems obvious to us that the brain processes information from the external environment, Maturana and Varela point to the impossibility of the brain having an external point of reference:

In order to back up their theory, Maturana and Varela point to the brain as a ‘living system’. The brain, they contend, is ‘closed, autonomous, circular and self-referential.’ (Morgan, 1998:216) Although it seems obvious to us that the brain processes information from the external environment, Maturana and Varela point to the impossibility of the brain having an external point of reference:

If one thinks about it, the idea that the brain can make true representations of its environment presumes some external point of reference form which it is possible to judge the degree of correspondence between the representation and reality. This implicitly presumes that the brain must have a capacity to see and understand its world from a point outside itself. Clearly, this cannot be so. (Morgan, 1998:216)

Taken as a metaphor for organizations, the theory of Autopoiesis has three main implications:

- Organizations are always attempting to achieve ‘self-referential closure… enacting their environments as extensions of their own identity.’

- Many of the problems that organizations encounter are a result of their attempt to maintain a particular identity.

- Explanations of organizational evolution, change and development must give attention to the factors that shape patterns affecting organizations.

Morgan contrasts what he calls ‘egocentric organizations’ with ‘systemic wisdom’. The former have a fixed notion of who or what they are and are determined to sustain this at all costs. ‘This leads them to overemphasize the importance of themselves while underplaying the significance of the wider system of relations in which they exist.’ (Morgan, 1998:219) The example Morgan gives is of ‘watchmakers’ and ‘typewriter firms’ failing to take account of developments in microprocessing and digital technologies. Their identity as producing a certain kind of equipment led to their downfall.

Contrasted with this is the idea of ‘systemic wisdom’ where organizations have an ‘evolving identity.’ Morgan believes that organizations can never survive being against their environment:

In the long run, survival can only be survival with, never survival against, the environment or context in which one is operating. (Morgan, 1998:221)

To be successful, therefore, organizations must be willing and able to transform themselves along with their environment in an evolutionary manner.

2. Chaos & complexity

Although it is usual to draw a clear distinction between ‘chaos’ and ‘complexity,’ Morgan (1998:222) states, it makes more sense in terms of organizations and their environments to consider them to be parts of the same interconnected (evolving) pattern. Using evolutionary theory as a touchstone, Morgan talks about the ‘random disturbances [that] can produce unpredictable events and relationships.’ However, ‘coherent order always emerges out of the randomness and surface chaos.’ (ibid.)

Although it is usual to draw a clear distinction between ‘chaos’ and ‘complexity,’ Morgan (1998:222) states, it makes more sense in terms of organizations and their environments to consider them to be parts of the same interconnected (evolving) pattern. Using evolutionary theory as a touchstone, Morgan talks about the ‘random disturbances [that] can produce unpredictable events and relationships.’ However, ‘coherent order always emerges out of the randomness and surface chaos.’ (ibid.)

Rather than internal complexity, randomness and diversity being organizationally-threatening, Morgan argues, they can actually become resources for change. Random systems develop an (albeit temporary) equilibrium as tension between two or more ‘attractor’ elements. These tensions will, every so often, lead to ‘bifurcation points’ due to changes in one or more of the attractor elements making the system unstable. Such ‘forks in the road’ lead to different futures and ways of operating for organizations.

Small changes can lead to huge consequences. The most famous example of this is the ‘butterfly effect’ where a small and insignificant event such as a butterfly flapping its wings in China can influence weather patterns on the other side of the world. The butterfly doesn’t cause in any meaningful sense the hurricane, but the tiny change it causes in its environment leads to another change and another change, and so on…

How can managers and leaders cope in the face of such chaos and complexity? Morgan suggests five key ideas:

- Rethinking what we mean by ‘organization’ – especially in terms of hierarchy and control

- Learning the art of managing and changing contexts

- Learning how to use small changes to create large effects

- Living with continuous transformation and emergent order as a natural state of affairs

- Being open to new metaphors that can facilitiate processes of self-organization (Morgan, 1998:226)

What do we mean by ‘organization’?

Although somewhat frightening, chaos and complexity theory stresses that there is no ‘grand design’ or central organizing principle at work in such systems. Instead, ‘patterns have to emerge’ without being imposed. Hierarchy and control are temporary conditions or outcomes of the system, mere ‘snapshot points’ on a self-organizing journey (as Morgan puts it).

The fundamental role of managers is to shape and create “contexts” in which appropriate forms of self-organization can occur. (Morgan, 1998:227)

This is an extremely insightful point, and one that resonates with me. Take setting up a new online community, which I’ve done (and attempted to do) a few times. An authoritarian, top-down approach is guaranteed not to work in this arena. Instead, as I’ve attempted to do with EdTechRoundUp, procedures, norms and contexts are negotiated that allow the organization to evolve successfully.

Changing contexts

Sometimes, if a particular system is inappropriate within an organization – for example a school or hospital is ‘failing’ and not reaching external targets, then the role of managers and leaders is to cause instability that causes the system to change. The aim of such instability would be to cause those within the organization to re-assess their role and day-to-day practice to change the system for the better. ‘The important point,’ says Morgan, ‘is that the manager helps to create the conditions under which the new context can emerge.’ (1998:230) Without creating these conditions, organizations ‘end up trying to do the new in old ways.’ (ibid.)

Small changes -> large effects

If systems are conceived as involving several ‘attractors’ that are in tension, it follows that changes in context are achieved by either introducing new attractors or changing the influence each attractor possesses. Doing this will generate ‘bifurcation points’ that affect future development – often by creating ‘tensions between the status quo and alternative future states.’ (Morgan, 1998:231)

Creating a paradox leads to system instability, and therefore a need for a ‘reframing’ of the situation which would resolve this paradox. Managers and leaders need to help change the system incrementally so fundamental change occurs. Such incremental changes can create a ‘critical mass’ effect which leads to an overwhelming force for change.

Emergence as ‘natural’

Leaders and managers cannot force complex systems into lasting comprehensive changes. They can merely nudge and push a system in the desired direction. They should be aware of feedback loops and provide room for experimentation with ‘new realities’. Introducing new images and metaphors of the roles of individuals within the organization can help

3. Mutual causality

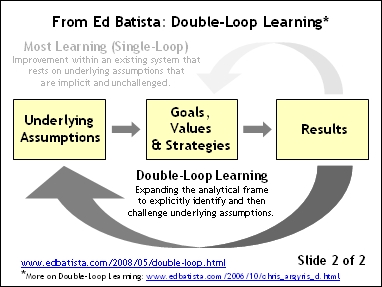

Change, according to the theories outlined above, does not unfold in a linear fashion but via circular patterns (loops not lines). A does not cause B under such a system. Instead both A and B ‘are co-defined as a consequence of belonging to the same system of circular relations.’ (Morgan, 1998:234) Magorah Maruyama has shown how positive feedback loops can lead to complex systems:

Change, according to the theories outlined above, does not unfold in a linear fashion but via circular patterns (loops not lines). A does not cause B under such a system. Instead both A and B ‘are co-defined as a consequence of belonging to the same system of circular relations.’ (Morgan, 1998:234) Magorah Maruyama has shown how positive feedback loops can lead to complex systems:

[A] large homogenous plan attracts a farmer, who settles on a given spot. Other farmers follow, and one of them opens a tool shop. The shop becomes a meeting place, and a food stand is established next to the shop. Gradually, a village grows as merchants, suppliers, farmhands, and others are attracted to it… [T]he homogenous plan has been transformed by a series of positive feedback loops that amplify the effects of the initial differentiation. (Morgan, 1998:235)

Often, human nature makes us want to explain and analyze situations in terms of finding a specific ’cause’. However, phenomena actually reside within overall patterns of positive and negative feedback.

Peter Senge, leadership guru and author of The Fifth Discipline believes that many systems are unstable because of delayed feedback between elements. This leads to people within organizations either underplaying or exaggerating their behaviours.

Morgan comes across as a great believer in loop analysis and presents some of his reasons for thinking so. Here are three of them:

- It cultivates ‘systemic wisdom’ – the approaching of organizational problems from a mindset that respects patterns of mutual causality.

- It provides insights on how small changes can have large effects.

- It invites us to understand the patterns that lock the system into vicious circles because of positive feedback loops.

4. Dialectical change

It is a truism that we cannot fully understand something without knowing its opposite. You cannot truly know the meaning of ‘hot’ unless you understand what ‘cold’ means. You cannot conceive of ‘day’ without knowing ‘night’. And so on. Such dialectical philosophy has a long history and tradition, chiefly through Taoist philosophy which originated in ancient China. This philosophy understands the universe to be subject to the dynamic interplay of yin and yang, creative and destructive powers.

It is a truism that we cannot fully understand something without knowing its opposite. You cannot truly know the meaning of ‘hot’ unless you understand what ‘cold’ means. You cannot conceive of ‘day’ without knowing ‘night’. And so on. Such dialectical philosophy has a long history and tradition, chiefly through Taoist philosophy which originated in ancient China. This philosophy understands the universe to be subject to the dynamic interplay of yin and yang, creative and destructive powers.

Dialectical principles

Taoist philosophy influenced the work of both Hegel and Marx who developed some of its principles into theories of social change. Morgan uses a neo-Marxian perspective in this section to settle upon three main principles:

Principle 1 – Whenever one person attempts to control another a process of resistance undermines that attempt. ‘The act of control itself sets up consequences that work against its effectiveness.’ (Morgan, 1998:245)

Principle 2 – Negations of negations retain something from that form, leading to an evolution in patterns of control.

Principle 3 – Changes in quantity lead to changes in quality. Water absorbs increases in temperature up to the boiling point. Camels can be loaded until the straw that breaks its back. ‘A process of control and countercontrol may continue until control is no longer possible, leading to a new phase of collaborative or destructive activity.’ (Morgan, 1998:245)

Putting these three principles together we can see that organizational arrangements set up contradictions and opposition by their very nature. This leads to a Hegelian process of negation and counter-negation. This process continues until a limit is reached and the qualitative state of the organization must change or be destroyed.

Dialectical management

Dialectic analysis has two main implications for management, believes Morgan:

- Restructuring is not a solution to a problem as it is itself a manifestation of a deeper problem. Instead, they should be dealt with through ‘social and political initiatives.’ (Morgan, 1998:248) Contradictions can only be tacked through an appreciation of what is creating the context in which they are able to flourish.

- Managers and leaders cannot wait for ‘macro-problems’ to present themselves. They must deal with ‘microflux’ in order to keep an organization running smoothly and understand ‘creative destruction.’

Managing paradox

If not managed properly, new initiatives or directions instituted to cause positive organizational change can become ‘mired in paradoxical tensions that undermine the desired change.’ (Morgan, 1998:249):

Although there may we ways of resolving the paradoxes, the fact that the tensions are experienced as contradictory may in itself be sufficient to negate transformational change. For example, if people feel that the new demands for “more innovation,” “improved morale,” “more collaboration,” “increased decentralization,” and so on, are inconsistent with what seems reasonable or possible, inertia is the most likely outcome. (Morgan, 1998:250)

To my mind, this seems almost as though leaders and managers, although being explicit about the organizational vision, should keep the purpose of other changes and maneuvers ‘hidden’ as this could prejudice their outcome?

‘Paradox,’ says Morgan (pace Kurt Lewin, whom he cites), ‘cannot be resolved by eliminating one side.’ (Morgan, 1998:251) The task of the manager or leader is to find a way to integrate competing elements. They must create new contexts that reframe the key contradictions in a positive way. For example, Japanese manufacturers have transformed a traditional paradox by showing how improving quality (by elimating waste, simplying processes, etc.) can lead to lower costs.

‘Creative destruction’

Dialectical processes directly affect innovation. New innovations lead to the destruction of established practice and displace old innovations. In turn, the solutions the innovations provide create a new set of problems, which require new innovations. And so the cycle continues. As Morgan notes, this leads to important implications – not least that innovations create the basis for their own downfall. :-p

Dialectical processes directly affect innovation. New innovations lead to the destruction of established practice and displace old innovations. In turn, the solutions the innovations provide create a new set of problems, which require new innovations. And so the cycle continues. As Morgan notes, this leads to important implications – not least that innovations create the basis for their own downfall. :-p

Many companies embrace the above and succeed in chaotic and turbulent environments because they ‘systematically destroy the breakthroughs created by their own products and initiatives by coming up with better ones.’ (Morgan, 1998:253)

Although so-called ‘creative destruction’ can be a powerful tool, it leaders must take care that it is not over-emphasized. Destruction should be a by-product of evolution, not a conscious aim.

Conclusion

Morgan outlines what he believes to be the three main strengths and the one major limitation of the ‘flux and transformation’ metaphor.

Strengths

- Offers new understandings of the nature and source of change.

- Offers new horizons of thought that can be used to enrich our understanding of management and leadership.

- Offers to leaders and managers a powerful new perspective on their role in facilitating emergent change.

Limitation

- Is ‘powerless power’ a message that managers and leaders really want to hear?

I’m a bit more cautious about embracing a ‘chaos and complexity’ model of organizational change. I’m much more comfortable with the ‘brain’ metaphor that I blogged about recently. However, I can see that if an organization is striving to become the ‘best of the best’ a decentralized anti-structure as proposed here would perhaps be the best method to achieve this.

What are YOUR thoughts? 😀

In order to back up their theory, Maturana and Varela point to the brain as a ‘living system’. The brain, they contend, is ‘closed, autonomous, circular and self-referential.’ (Morgan, 1998:216) Although it seems obvious to us that the brain processes information from the external environment, Maturana and Varela point to the impossibility of the brain having an external point of reference:

In order to back up their theory, Maturana and Varela point to the brain as a ‘living system’. The brain, they contend, is ‘closed, autonomous, circular and self-referential.’ (Morgan, 1998:216) Although it seems obvious to us that the brain processes information from the external environment, Maturana and Varela point to the impossibility of the brain having an external point of reference: Although it is usual to draw a clear distinction between ‘chaos’ and ‘complexity,’ Morgan (1998:222) states, it makes more sense in terms of organizations and their environments to consider them to be parts of the same interconnected (evolving) pattern. Using evolutionary theory as a touchstone, Morgan talks about the ‘random disturbances [that] can produce unpredictable events and relationships.’ However, ‘coherent order always emerges out of the randomness and surface chaos.’ (ibid.)

Although it is usual to draw a clear distinction between ‘chaos’ and ‘complexity,’ Morgan (1998:222) states, it makes more sense in terms of organizations and their environments to consider them to be parts of the same interconnected (evolving) pattern. Using evolutionary theory as a touchstone, Morgan talks about the ‘random disturbances [that] can produce unpredictable events and relationships.’ However, ‘coherent order always emerges out of the randomness and surface chaos.’ (ibid.) Change, according to the theories outlined above, does not unfold in a linear fashion but via circular patterns (loops not lines). A does not cause B under such a system. Instead both A and B ‘are co-defined as a consequence of belonging to the same system of circular relations.’ (Morgan, 1998:234)

Change, according to the theories outlined above, does not unfold in a linear fashion but via circular patterns (loops not lines). A does not cause B under such a system. Instead both A and B ‘are co-defined as a consequence of belonging to the same system of circular relations.’ (Morgan, 1998:234)  It is a truism that we cannot fully understand something without knowing its opposite. You cannot truly know the meaning of ‘hot’ unless you understand what ‘cold’ means. You cannot conceive of ‘day’ without knowing ‘night’. And so on. Such dialectical philosophy has a long history and tradition, chiefly through Taoist philosophy which originated in ancient China. This philosophy understands the universe to be subject to the dynamic interplay of yin and yang, creative and destructive powers.

It is a truism that we cannot fully understand something without knowing its opposite. You cannot truly know the meaning of ‘hot’ unless you understand what ‘cold’ means. You cannot conceive of ‘day’ without knowing ‘night’. And so on. Such dialectical philosophy has a long history and tradition, chiefly through Taoist philosophy which originated in ancient China. This philosophy understands the universe to be subject to the dynamic interplay of yin and yang, creative and destructive powers. Dialectical processes directly affect innovation. New innovations lead to the destruction of established practice and displace old innovations. In turn, the solutions the innovations provide create a new set of problems, which require new innovations. And so the cycle continues. As Morgan notes, this leads to important implications – not least that innovations create the basis for their own downfall. :-p

Dialectical processes directly affect innovation. New innovations lead to the destruction of established practice and displace old innovations. In turn, the solutions the innovations provide create a new set of problems, which require new innovations. And so the cycle continues. As Morgan notes, this leads to important implications – not least that innovations create the basis for their own downfall. :-p![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=8a0a0202-330b-44e3-89c1-e0c5df6e06f0)