Trust no-one: why ‘proof of work’ is killing the planet as well as us

Note: subtlety ahead. This post uses cryptocurrency as a metaphor.

As you may have read in the news recently, the energy requirements of Bitcoin are greater than that of some countries. This is because of the ‘proof of work‘ required to run a cryptocurrency without a centralised authority. It’s a ‘trustless’ system.

While other cryptocurrencies and blockchain-based systems use other, less demanding, cryptographic proofs (e.g. proof of stake) Bitcoin’s approach requires increasing amounts of computational power as the cryptographic proofs get harder.

As the cryptographic proofs serve no function other than ensuring the trustless system continues operating, it’s tempting to see ‘proof of work’ as inherently wasteful. Right now, it’s almost impossible to purchase a graphics card, as the GPUs in them are being bought up and deployed en masse to ‘mine’ cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin.

Building a system to be trustless comes with huge externalities; the true cost comes elsewhere in the overall system.

🏭 🏭 🏭

Let’s imagine for a moment that, instead of machines, we decided to deploy humans to do the cryptographic proofs. We’d probably question the whole endeavour and the waste of human life.

The late Dave Graeber railed against the pointless work inherent in what he called ‘bullshit jobs‘. He listed five different types of such jobs, which comprise more than half of work carried out by people currently in employment:

- Flunkies — make their superiors feel more important (e.g door attendants, receptionists)

- Goons — oppose other goons hired by other people/organisations (e.g. corporate lawyers, lobbyists)

- Duct Tapers — temporarily fix problems that could be fixed permanently (e.g. programmers repairing shoddy code, airline desk staff reassuring passengers)

- Box Tickers — create the appearance that something useful is being done when it is not (e.g. in-house magazine journalists, corporate compliance officers)

- Taskmasters — manage, or create extra work for, those who do not need it (e.g. middle management, leadership professionals)

What cuts across all of these is the ‘proof of work’ required to keep the status quo in operation. This is mostly obvious through ‘Box Tickers’, but it is equally true of middle management ensuring work is seen to be done (and that hierarchical systems prevail).

✅ ✅ ✅

There is much work that is pointless, and it could be argued that an important reason for this is because we have a trustless society. For example, when some of the most marginalised people in our communities ask for help between jobs, we require them to prove that they are spending 35 hours per week looking for one. It’s almost as if someone in government has taken the pithy phrase “looking for a job is a full time job” and run with it.

Western societies have been entirely captured by the classic economic argument that everything will turn out well if we all act in our own self-interest. I’m not sure if you’ve looked around you recently, but it seems to me that this model isn’t exactly… working?

It’s my belief, therefore, that we need to engender greater trust in society. Ideally, this trust should be inter-generational and multicultural, seeking to build bridges between different groups, rather than building solidarity in one group at the expense of others.

This is not a call to naivety: I’m well aware that trust comes in different shapes and sizes. What I think we’re losing, however, is an ability to trust people with small things. As a result, we’re out of practice when it comes to bigger things.

👁️ 👁️ 👁️

The Russian phrase Доверяй, но проверяй means, I believe, “trust, but verify”. It’s a useful approach to life, and an approach I use with everyone from members of my family to colleagues on various projects I’m working on.

The important thing here is the ‘trust’ part, with the occasional ‘verify’ to ensure that people don’t, well, take the piss. What we’re seeing instead is ‘verify and verify’, and increasing verificationism where we spend our lives proving who we are as well as our eligibility. This disproportionately affect already-marginalised people. It is a burden and tax on living a flourishing human existence.

🧑🤝🧑 🧑🤝🧑 🧑🤝🧑

Back in 2013, I wrote a series of blog posts reflecting on a talk by Laura Thomson entitled Minimum Viable Bureaucracy. In one of these entitled Scale, Chaordic Systems, and Trust I wrote:

You can build trust “by making many small deposits in the trust bank” which is a horse-training analogy. It’s important to have lots of good interactions with people so that one day when things are going really badly you can draw on that. People who have had lots of positive interactions are likely to work more effectively to solve big problems rather than all pointing fingers.

To finish, then, I want to reiterate two things that Laura Thomson recommended that anyone can do to build trust:

- Begin by trusting others

- Be trustworthy

Solidarity begins at home.

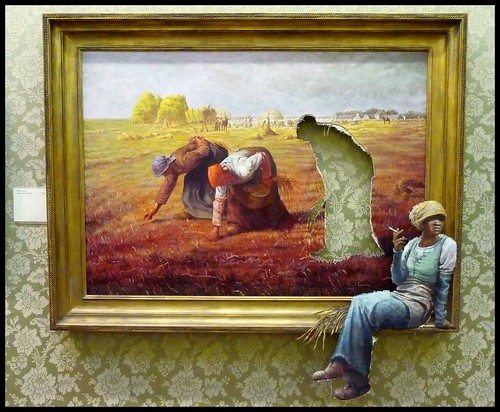

This post is Day 87 of my #100DaysToOffload challenge. Want to get involved? Find out more at 100daystooffload.com. Image by Banksy.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=6ddcd762-88c3-44c2-9aba-8aeabdbec6f2)