We need education for resilience, not flexibility.

If there’s one thing that educators, and especially those involved in educational technology agree upon, it’s that the time for ‘business as usual’ as come to an end:

All of us, especially within the EdTech community, can begin to think about how to develop ‘resilient education’. That is, a pedagogy and curriculum that both encourages and fosters the radical change that is necessary as well as ensuring that the present depth, breadth and quality of education is sustainable in a future where there may be less abundance and freedom than we have become accustomed to. (Joss Winn, 2009)

Whilst I certainly wouldn’t label myself a Marxist, I do agree with Richard Hall’s critique of Capitalism and the enclosure of public spaces where ‘non-legitimised’ skills currently flourish:

A global range of skills, alongside stories in which they might be situated, exist in spaces that remain as yet unenclosed. These spaces might be harnessed collaboratively for more than profiteering, or the extraction of surplus value or further accumulation or financialisation, or alienation. We teach and re-think these skills and these ways of thinking every day with other staff and students and within our communities of practice. We need the confidence to imagine that our skills might be shared and put to another use. We need the confidence to defend our physical and virtual commons as spaces for production and consumption. We need the confidence to think ethically through our positions. We need the confidence to live and tell a different story of the purpose of technology-in-education. (Richard Hall, 2011)

We can see this in the way, for example, Pearson have labelled their new, ‘free’ LMS offering ‘OpenClass’ and Blackboard talk about the way their system is ‘open’ because academics can choose to CC license work within their system. It’s nothing less than the commoditisation of Open Education.*

Look up the word flexibility. What does it mean?

1. capable of being bent, usually without breaking; easily bent: a flexible ruler.

2. susceptible of modification or adaptation; adaptable: a flexible schedule.

3. willing or disposed to yield; pliable: a flexible personality.

And now look up resilience:

1. the power or ability to return to the original form, position, etc., after being bent, compressed, or stretched; elasticity.

2. ability to recover readily from illness, depression, adversity, or the like; buoyancy.

There’s a subtle difference between the two positions: one is active and one is passive. One is future-shaping and empowering whilst the other looks for authority elsewhere.

I know what I think we should be educating for.

*Have a look at CUNY’s Commons in a Box project.

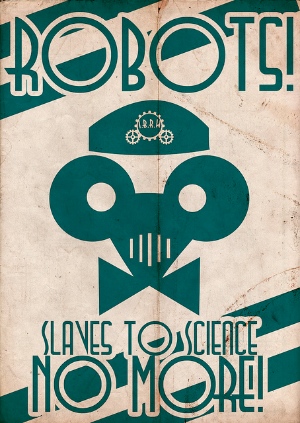

Almost every sci-fi film you will ever see will feature some kind of robot. In some of these robots can be a force for good (

Almost every sci-fi film you will ever see will feature some kind of robot. In some of these robots can be a force for good (