TB872: Schön’s swamp and ‘ideas in good currency’

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

It’s a delight to be introduced to thinkers who are not only new to you, but who have a sizable body of work you can go back through. It’s even better when they were alive at a time to have been recorded on video, as is the case with Donald Schön.

Schön was the Ford Professor of Urban Studies and Education at MIT from 1972 until his death in 1997. Before this, he worked at an agency on ideas which complemented Thomas Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions and was invited to give the BBC’s Reith Lectures in 1970 on the topic of going beyond the ‘stable state’.

In this post, I’m going to reflect on the first lecture (transcript) of his Reith Lectures as well as an extract from a video of a lecture given at Iowa State University in 1989, in which Schön discusses the nature of design practice and education. My aim is to give my understanding of some of the concepts which he discusses. But first, let’s look at a famous metaphor he uses:

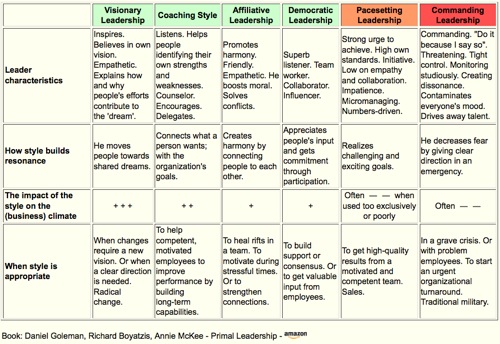

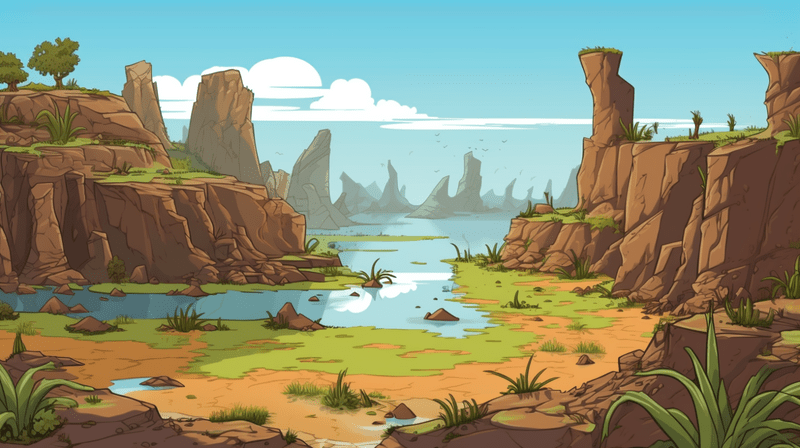

…I’d like to set the stage… by talking more broadly about the professions, and suggest to you that every profession, both major and, as they’re sometimes called, minor professions, is now confronting what might be called a dilemma of rigour or relevance. And one way to conceptualise that is to think about a kind of topography of practice in which you have, first of all, a very high, dry cliff, and underneath it a swamp. And on the high ground you can complete the work of your PhD dissertation, you can make econometric models, you can model inventory control systems.

The problem is that, on the high ground, the problems that you’re working on are relatively trivial. In the swamp below, you can work on what you take to be the really important social and technological problems of the age, but you don’t know how to be rigorous in any way that you can name. And so your choice is to be rigorous and trivial on the high ground or to be working on really important problems but not in any way that you can define as rigorous in the swamp – high ground or swamp.

And I think that issue confronts most of my students who’ve entered into professional work. It confronts people on the leading edge of most professions. I think it confronts people in the design professions as well.

(Lecture at Iowa State University, in The Open University, 2021)

The Stable State

Schön’s concept of the ‘stable state’ refers to the deeply held belief in the constancy, predictability, and unchangeability of certain central aspects of our lives and society. It embodies the notion that there exists a state of equilibrium or permanence in personal identities, organisational structures, societal norms, and technological advancements. Significant significant changes to these are seen as rare or can be effectively managed to maintain stability.

Belief in the stable state is belief in the unchangeability, the constancy, of certain central aspects of our lives, or belief in the attainability of that kind of constancy: it’s deep and strong within us. We institutionalise it in every social domain. We do this in spite of our talk about change, our apparent acceptance of change, our approval of dynamism. Language about change is for the most part talk about very small change—trivial in relation to a massive, unquestioned stability—which nevertheless appears formidable to its opponents by the same peculiar optic that leads a potato chip company to see a larger bag of potato chips as a new product. Moreover, talk about change is as often as not a substitute for engaging in it.

[…]

Belief in the stable state is central, because it is a bulwark against the threat of uncertainty. Given the reality of change, we can maintain belief in the stable state only through tactics of which we are largely unaware. Consequently our responses to attacks on the stable state have been responses of desperation, largely destructive, and our need is to develop institutional structures, ways of knowing, and ethics, for the process of change itself.

[…]

The feeling of uncertainty is anxiety, and the depth of the anxiety increases as the threatening changes strike at more central regions of the self. In the last analysis, the degree of threat presented by change depends upon its connection with self-identity, and against all this we’ve erected our belief in the stable state.

(BBC, 1970)

Highlighting the limitations of this belief in the face of the dynamic, complex, and often unpredictable nature of modern societies, Schön argues that clinging to the idea of a stable state prevents individuals and institutions from effectively responding to, and engaging with, the continuous and often rapid changes that characterise contemporary life. These include technological advancements, social transformations, and environmental challenges. This is even more true in the 2020s than the 1970s.

Public Learning and ‘Ideas in Good Currency’

The process by which societies, organisations, or groups learn collectively is what Schön calls ‘public learning’. This is often in response to changes or challenges in the environment, more recently due to having to confront the loss of the ‘stable state’. This requires a collective learning process to adapt to new realities that result from this loss. Public learning is a concept that emphasises the importance of shared understanding and adaptation to navigate uncertainties and encourage resilience in the face of change.

[W]hen our diffusion curves get below 30 years, below 20 years, then the social impact generated by that technology lies well below the limit for generational adaptation, and you and I within our own lifetimes have to handle the kind of adaptations that used to be handled as one generation passed into another. These are real human limits and technology transgresses them.

(BBC, 1970)

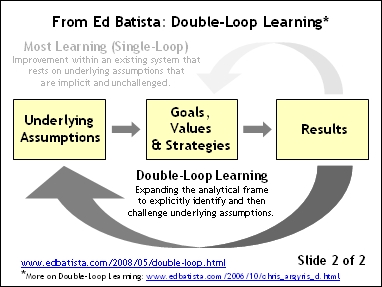

Ideas that are widely accepted and used within a society or professional community are described by Schön as ‘ideas in good currency’. This is often because they offer effective solutions to current problems or resonate with prevailing values and beliefs. Thomas Kuhn suggests that science progresses almost generationally as scientists retire or die, due to the way that ideas are framed. Schön suggests that, due to the end of the ‘stable state’, we require new learning systems that allow societies to learn intra-generationally. This allows the circulation of new, valuable ideas to address contemporary challenges.

Effective Learning Systems

To be considered ‘effective’ according to Schön, learning systems need to be capable of self-transformation, adaptability, and of handling uncertainty. They must enable individuals and institutions to reflect, learn from experiences, and continuously innovate. These learning systems should bring about an environment where questioning, experimentation, and the application of new knowledge are encouraged and supported.

If Schön’s learning systems are characterised by their adaptability, reflexivity, and capacity for continuous learning, then the focus is on an ability to incorporate new insights into policy and practice. These systems thrive on diversity of thought and flexibility in response to new information and challenges.

Dynamically Conservative Social Systems

Schön suggests that even in the face of necessary change, social systems often exhibit a dynamically conservative nature, striving to maintain core identities and values while adapting to new conditions. We can see this with the climate emergency. His model implies a balance between preserving essential characteristics of the system and incorporating innovative practices for evolution and growth.

In a situation of uncertainty, the problem that you face is the problem of constructing a problem because you don’t know what the problem is. And the problem of constructing a problem is not a technical problem. In fact, the opposite is true. You have to construct the problem before you can carry out any technical activity.

[…]

So problems of uncertainty, situations of uncertainty, are not technical problems. Because you have to frame the problem before you get to a technical problem. Situations in which you’re dealing with a unique case are not technical problems because you can’t apply the rules to them. By definition, they fall outside the rules. And situations of conflict are not technical problems because we have no clear and self-consistent set of ends to try to meet. You have to reconcile ends before you can solve the problem. These indeterminate zones of practice have become more and more powerful over the last 20 years, I think.

(Lecture at Iowa State University, in The Open University, 2021)

Policy formation and implementation is complex, particularly within the context of uncertain and constantly-changing environments. Effective policy-making therefore requires a learning system approach, where policies are formed through iterative processes of experimentation, reflection, and adaptation, rather than through static, one-time decisions. This reminds me somewhat of DAD vs EDD.

Governments as Learning Systems

In an ideal world, governments would be proactive in identifying societal needs, thinks Schön, as well as being responsive to changing conditions, and capable of experimenting with innovative solutions. He suggests that governments need to develop mechanisms for continuous learning and adaptation to effectively address complex, evolving societal challenges.

Constructive responses to the loss of the stable state must confront the phenomenon directly. They have to do it at the level both of the person and of the institution. If our institutions are threatened with disruption, how can we invent or modify them in such a way that they are capable of transforming themselves without flying apart at the seams? If we are losing stable values and anchors for identity, how do we preserve self-respect while in the process of change?

(BBC, 1970)

Schön argues that governments should shift from a model of static governance, based on maintaining a ‘stable state,’ to a dynamic learning system approach. This change is necessary to effectively address the increasingly complex, uncertain, and rapidly evolving challenges of modern societies. By embracing a role as a facilitator of public learning, experimentation, and adaptation, governments can better serve the needs of their citizens. This should lead to more resilient, responsive, and innovative societies.

References

- BBC (1970). ‘The Reith Lectures, Donald Schön – Change and Industrial society’. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00h65rn (Accessed: 17 February 2024).

- The Open University. (2021). ‘3.3.1 Schön: situations as learning systems’, TB872: Managing change with systems thinking in practice. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2171593§ion=3.3.1 (Accessed 17 February 2024).

Image: Midjourney (“Cartoon style image with NO TEXT NO HUMANS NO ANIMALS showing a natural landscape with some high ground on a cliff overlooking a swamp. The scene on the high ground looks arid and boring. The swamp looks like it’s complicated and teeming with plant life. There should be a big difference in height and vibe between the high ground and low ground, including a cliff. –ar 16:9 –v 5.1”)