TB872: Overview of different traditions in social learning systems

Note: this is a post reflecting on one of the modules of my MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. You can see all of the related posts in this category.

Life is short, and so I have fed all of the blog posts I’ve written over the last couple of weeks into ChatGPT to generate the table below. I’ve linked to each individual post I wrote in the ‘Tradition’ column.

This ‘reading matrix’ was given as part of the course activities. I should, I suppose, have been filling it in as I went along.

A the WordPress theme I’m using is quite narrow, you’ll either have to pinch-to-zoom (mobile) or press CTRL and + (desktop) to increase the font size.

| Tradition | Concepts | Lessons about the nature of learning | Lessons about designing learning systems | Other useful points | Problems & disagreements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schön: situations as learning systems | Dilemma of rigor or relevance The stable state Public learning Ideas in good currency Effective learning systems Dynamically conservative social systems | Learning is about adapting to significant, complex issues in “the swamp” below the rigour of “high ground”. Public learning is key in adapting to changes, especially in the loss of the ‘stable state’. | Learning systems must enable adaptability, reflexivity, and continuous learning. They should foster an environment of questioning, experimentation, and application of new knowledge. | Schön’s work underlines the importance of intra-generational learning due to rapid technological and social changes. Governments should act as learning systems to effectively address societal challenges. | The precise methods for maintaining rigor while addressing complex real-world problems can be contentious. There might be disagreement on how to implement and balance the elements of effective learning systems. |

| Vickers: appreciation and appreciative systems | Appreciative systems Readiness-to-do vs. readiness-to-value Standards of value Feed-forward | Learning involves both observing and engaging as an agent, valuing and interpreting our experiences. Learning is a complex activity that goes beyond action readiness to include ethical decisions and emotional responses. | Learning systems should be designed to accommodate changing values and standards, allowing for the representation and rehearsal of possible futures. | Vickers emphasises the importance of personal experience in shaping our understanding and the creation of shared ‘appreciated worlds’. Ethical considerations are expanding, suggesting a need for learning systems that are responsive to evolving ethical standards. | There may be challenges in reconciling the subjective nature of appreciative systems with the objective standards often sought in learning systems. The concept of ‘harm’ and ethical standards are subjective and can lead to disagreements on what constitutes ethical behavior. |

| Bateson: willingness to learn | Deutero-learning Metavalues Pluralism | Learning is an ongoing, lifelong process that should remain flexible and adaptable. It involves the willingness to modify and integrate new values into existing ones. | Learning systems should facilitate the integration of new understandings and values, reflecting societal changes and diversity. | Bateson emphasizes the interconnectedness of life and the importance of understanding complexity. She advocates for reconceptualising rights and responsibilities beyond the individual to include communities and ecosystems. | The definition and scope of independence can be contentious, as Bateson suggests it is an illusion, which might conflict with some cultural values and ideologies. |

| Bawden: critical social learning systems | Cognition, metacognition, and epistemic cognition Holocentric, ecocentric, egocentric, technocentric perspectives Emergence Critical Social Learning Systems (CSLS) | Learning is a transformative process at different cognitive levels: understanding the matter at hand, the methods of learning, and the limits to our understanding. Learning should lead to a change in behaviour based on the knowledge acquired. Living is a constant process of learning and adapting to change. | Learning communities should incorporate experiential learning, epistemic cognition, and a critical evaluation of worldviews. Learning systems should be designed with awareness of their coherence, diversity, purpose, emotional ambience, and power dynamics. | Bawden emphasises the importance of adapting learning to complex, dynamic, and degrading environments. The ‘map is not the territory’ highlights the distinction between conceptual models and real-world complexities. | The complexity of Bawden’s integrated CSLS diagram may present challenges in understanding and application. |

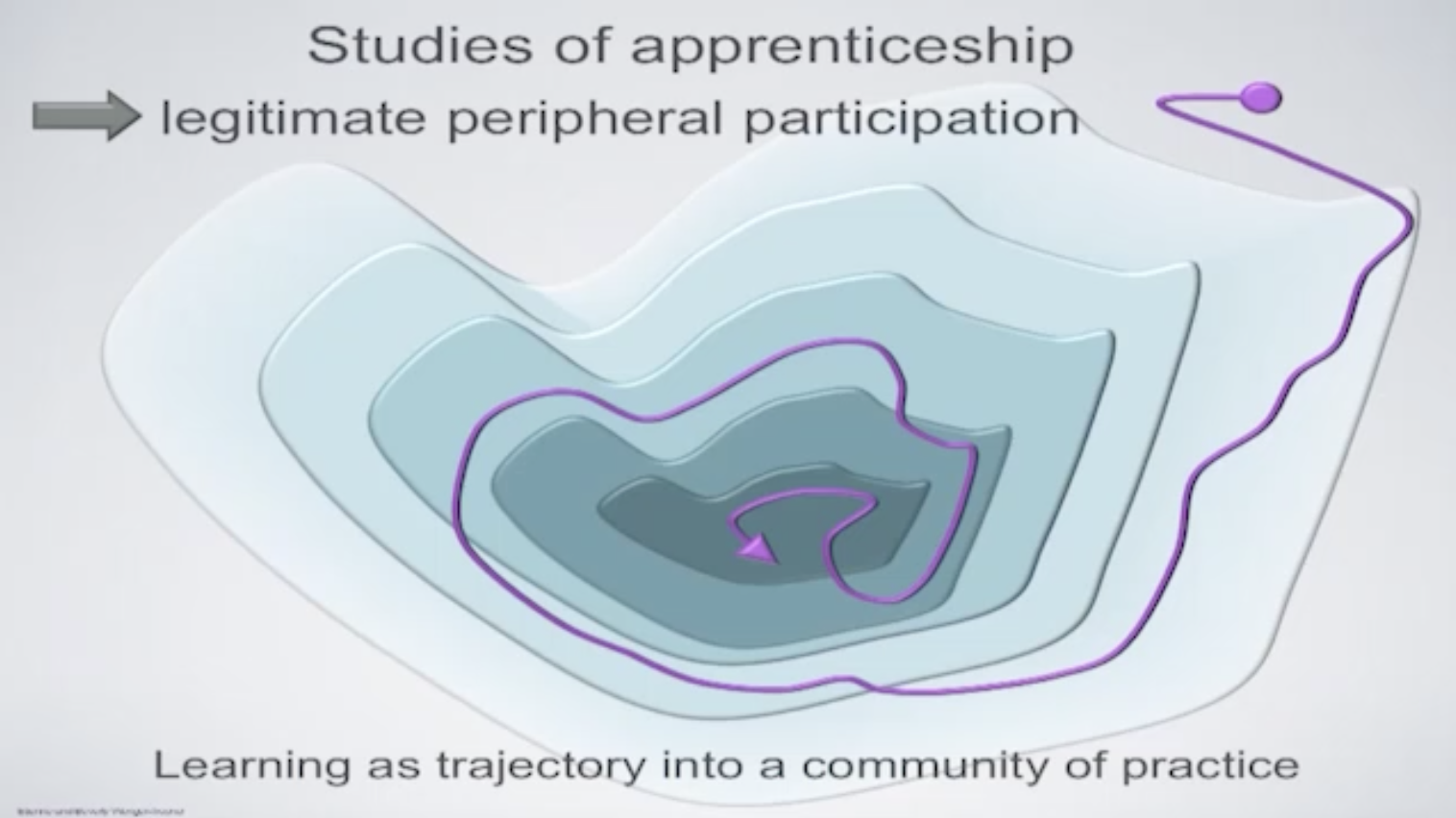

| Wenger-Trayner: communities of practice | Community of Practice (CoP) Legitimate peripheral participation Learning as a trajectory into a community of practice World learning system | Learning is social and involves entire communities, not just transactions between a master and an apprentice. Communities shape our perception and interpretation of experiences. | Learning systems must facilitate social, professional, and personal support through CoPs, particularly in a globalised context. CoPs should have action-learning capacity, cross-boundary representation, and cross-level linkages. | The concept of ‘world design’ through strategic social learning systems is key. Brokers play a crucial role in interweaving relationships within and between communities. Trust and conflict resolution within CoPs are important and take time to develop. | CoPs are not a panacea for all world problems but should be part of a broader ecology of structures and systems. There can be challenges in stewardship within CoPs, especially in addressing civic issues. |

| Non-Western traditions: Ubuntu | Humanity to others “I am what I am because of who we all are” | Learning and identity are communal, not individual. Acknowledges the importance of social relationships and community in learning. | Learning systems should foster a sense of belonging and collective responsibility. Systems should encourage sharing and collaboration, reflecting the communal aspects of Ubuntu. | Ubuntu challenges individualistic and competitive approaches, promoting inclusivity and cooperation. | The implementation of Ubuntu in diverse cultural contexts may lead to differing interpretations and applications. |

| Non-Western traditions: Pratītyasamutpāda | Dependent origination Interdependence of phenomena | Emphasises the interconnectedness of knowledge and existence. Recognises that understanding is not linear but multidimensional. | Systems should be designed to reflect the complex interplay of multiple causes and effects. Encourages holistic thinking and the use of tools like causal loop diagrams to visualise interconnections. | Offers a worldview that counters reductionist and segmented approaches. Supports environmental and social activism by highlighting interconnectedness. | May challenge entrenched Western notions of causality and individualism, creating philosophical and practical tensions. |